The cavernous medieval warrens of the Arsenale, a complex of former armories and shipyards that powered the Venetian navy, will make way for a 21st-century battle over the next six months. “Reporting From the Front”, the theme of the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale, asks how shaping the built environment can improve the human condition. Don’t expect navel-gazing exercises in postmodernism or starchitect monuments to ego, but rather projects highlighting architectural social responsibility and equitable urban design, even planning projects with little design aspect.

This year’s biennale, which runs from May 28 to November 27, was curated by Pritzker-winning Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, principal of the firm Elemental. His “half a good house” concept reimagined social housing in the developing world by offering the skeleton of a solid house, which families could adapt and build upon to suit their needs.

“‘Reporting From the Front’ will be about sharing with a broader audience, the work of people that are scrutinizing the horizon looking for new fields of action, facing issues like segregation, inequalities, peripheries, access to sanitation, natural disasters, housing shortage, migration, informality, crime, traffic, waste, pollution and participation of communities,” Aravena wrote in his curator’s statement.

The U.S. pavilion has taken its inspiration from Detroit, the once and future city of America’s innovations in industrialization and new technology — from Fordist factory floors to paved roads to suburban shopping malls to techno. In all its faded glory and promised phoenix-like rise from the ashes, the Motor City has been the subject of seemingly endless thought experiments in urbanism, many of them on display in Venice, even as the city must contend with a resource-draining roster of vacant land and emerging from municipal bankruptcy.

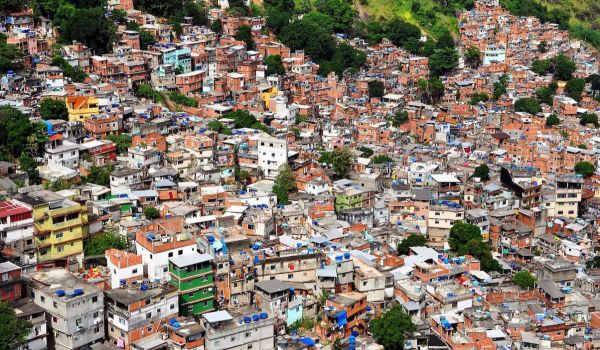

Brazil, meanwhile, makes an assertive case that socially relevant architecture must exist in the urban context and respect the people that inhabit workaday neighborhoods. The country’s exhibit, “Juntos” (Together), even argues that rudimentary planning tools like street signage and bike lanes deserve lofty recognition because of the way they empower everyday citizens, especially in marginalized communities. Curator Washington Fajardo, president of the Rio World Heritage Institute, selected 15 projects nationwide (though with a hometown tilt toward Rio) — some of which don’t involve buildings at all.

While Rio’s overblown stadium projects will occupy the media limelight during the Olympic Games in August, those visiting the Venice Biennale will instead see much less flashy but far more lasting grassroots efforts by nonprofits, like a project in the Maré favela to install street signs in the absence of municipal recognition. A multiyear effort by the Rio office of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) to plot bike routes in the city’s resurgent downtown rewards as much the process — intensive consultation with the cycling community — as the product.

“I believe Ciclo Rotas [Bike Routes] was selected primarily for its activist nature,” ITDP’s Brazil Director Clarisse Linke says. “[It] created the possibility for activists, cyclists or not, to become urbanists.”

Other innovative selections include a methodology for assessing the urban design quality of Brazil’s new wave of public housing — notorious for plunking people down far from jobs and transit — and a park with an urban garden in Rio’s Vidigal favela. Both projects were predicated on intensive collaboration with local residents.

More traditional “architecture,” Vila Flores in Porto Alegre is renovated industrial-era worker housing that has been transformed into live-work space for artists as part of an effort to revitalize the ailing 4º Distrito.

“Participating in the Venice Biennale is a unique opportunity to share the experience we are having in Porto Alegre,” say architects João Felipe Wallig and Márcia Braga, the latter of whom has a work space in Vila Flores. “It involves the understanding of architecture as a process arising from new social and cultural demands alongside historic preservation.”

But Fajardo saved his highest accolades for two “protagonists” out of the 15 projects. Both from Rio, they emphasize the city’s Afro-Brazilian heritage, which Fajardo has staunchly defended through his preservation work and public advocacy. In March, he went so far as to call for the upcoming Summer Games to be the “Black Olympics” in a March op-ed (Portuguese only) so that visitors to Rio would come away with a deeper appreciation of the city’s strongly African influence.

The two lead projects are Madureira Park, a lavish public space in an underserved, historically black neighborhood, and the African Heritage Cultural Circuit, a proposed network of historic sites and design interventions to highlight the history of the largest slave port in the Americas.

“The two projects have parallels, and I hope the momentum from the biennale brings attention to the pressing need for capital investment in the African Heritage Cultural Circuit,” said project designer Sara Zewde, in a Next City profile last year. One of the key sites along the circuit, the Valongo Wharf, has been recommended for UNESCO World Heritage status.

While Zewde is thrilled with the recognition, Fajardo intentionally gave equal credit to the architect and the “social agent” that helped make the project a reality. In this case, a city-sanctioned working group of black activists and scholars. The approach underpins the exhibit’s “Together” title, Zewde said, “suggesting that all three are authors, of works that are incomplete without referencing the other.”

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

_on_a_Sunday_600_350_80_s_c1.jpeg)