This story was co-published with El Paso Matters as part of our joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellowship For Borderland Narratives.

When married architect duo Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller moved to El Paso to teach at Texas Tech University, the couple hoped to bring their car-free New York City lifestyle to the borderland.

But it quickly became apparent that their new city’s desert conditions and infrastructure would not let them.

“We recognized that it is unbearable to walk to work every day, even in September or October,” says Kripa, now director at the Huckabee College of Architecture. “It’s just so hot, and there’s nowhere to have shade as a pedestrian.”

Housed inside the historic Union Depot Station in downtown El Paso, the school serves as a classroom and office for POST, or Project for Operative Spatial Technologies – an experimental investigative, territorial think-tank situated on the U.S.-Mexico border – where the two academics developed a program and an algorithm that identifies shade inequity.

Whether through trees or infrastructure, shade equity refers to equal availability and access to shade in different areas of a city and among people of all racial, ethnic, and income groups – particularly in public spaces.

POST focuses on different issues, including air quality, UV protection, and their irradiated shade project — the unseen dangers of UV radiation in shaded conditions.

“You might feel like you can be outside for a long time, but you’re being pretty highly irradiated by scattered ultraviolet rays,” Mueller says.

That’s especially the case in El Paso and other desert environments where “there’s a lot of airborne particulate in the air in the atmosphere,” he explains. Their research focuses on the UV damage and exposure in the region related to desertification and urbanization on the U.S.-Mexico border; it can be used in other cities with similar climates.

As part of their research, the couple produced maps that visualized a correlation between income levels, ZIP codes and urban shade equity. The idea, they explain, is to map the inequitable access to shade and the inequitable exposure to radiation by various communities and demographics.

“Once we understand exactly which underserved populations have access to which type of UV protection, the maps become real,” Kripa says. “Border crossings are totally exposed to UV damage.”

Indeed, the duo’s research found that those that are the most exposed to UV include people waiting outside for public transport or crossing the border on international bridges which are open and exposed. “They have a lot less access to shade versus other neighborhoods in El Paso that are more affluent that might have more access to big tree canopies in the shade,” Kripa says.

A woman carries an umbrella for shade as she walks along Paisano Drive in Downtown El Paso. (Photo by Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Irradiation can cause skin damage and serious health risks to those facing shade inequity on both sides of the border. “The U.S. has its environmental data, and Mexico has its environmental data,” Mueller says. “There are fewer and fewer collaborations across borders to share environmental data in order to understand the particular dynamics and identify vulnerable neighborhoods.”

To bridge the gap in environmental data between the two countries, POST constructs maps using satellites that span the jurisdictional borders. The satellites pick up areas with high levels of outdoor activity and analyze the available shade.

“We design and analyze the data with 3D technology, and that enables us to get a much clearer picture,” Mueller says. “Irradiated shade correlates directly to how much sky you can see from under a shade canopy.”

The data of shade canopy and sky views are then run through an algorithm created specifically to find the available threats of UV radiation.

“This algorithm is able to draw the visible area of the sky from any point in the city,” Mueller says. “We’re able to deploy the algorithm in all corners of the borderland. We put them in every pedestrian intersection to understand the shape of the sky at each intersection and the relative radiation exposure.”

The tool also helps identify comfort under shade conditions by looking at several factors, including UV damage, temperature, and quality of shade available.

“It’s about analyzing environments where humans have made assumptions that if you’re in the shade, you’re good to go, you’re protected,” Kripa says. “It’s looking at other atmospheric phenomena under the shade that continue to inflict damage on the human body. So the tool, hopefully, will evolve. We’re working on adding layers of analysis.”

The tool creates dome figures of a given area, analyzing the various layers of atmospheric phenomena.

“Looking at the representation of sky domes, we can make judgments about a given site, like which corner would be the most in need of intervention,” says Mueller. “There are several types of architectural interventions. The tool helps designers see how various three-dimensional structures impact access to radiation.”

Practical applications

With those computational analyses done, the architects can work on designing precise shade structures and canopies – these would fulfill the same function as trees, which require a lot of water, a resource scarce in desert areas.

“What we’re trying to test now is whether or not we can design shade structures that are not trees … that address these very specific issues,” Kripa says.

One of their designs will soon be tested with the nonprofit Insights Science Discovery, where they will create an outdoor classroom near Mount Cristo Rey in Sunland Park.

“The idea is to use a 60-foot enormous outdoor classroom shade structure as a prototype or as a testing built model to understand whether the research we’re producing [can be used to make policy recommendations],” Kripa says. “The hope is…to provide the city with the data that we have.”

The plan for the structure began in 2020, during the pandemic. Mueller and Kripa were working on their UV radiation protection research when Insights approached them about creating a financially feasible outdoor classroom.

“In our mind, it had to meet all these requirements to protect against UV damage, but it also has to be perforated so that the wind can go through it and not rip it up,” says Kripa.

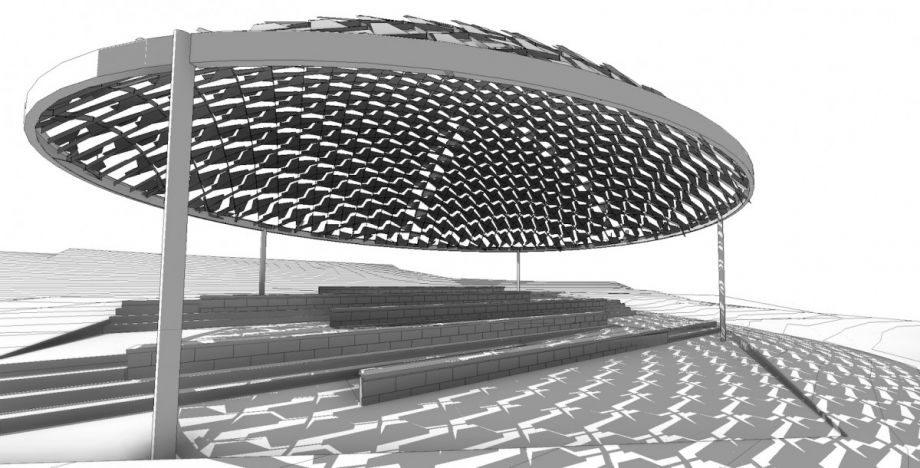

Renderings of a structure that will be built for the nonprofit organization Insights Science and Discovery near Mount Cristo Rey using a data tool to maximize shade equity. (Courtesy Project for Operative Spatial Technologies)

Alysha Swann, executive director for Insights Science Discovery, expects to see the dome project used as soon as the fall of 2023 or spring of 2024 near Mount Cristo Rey in New Mexico, within miles of El Paso.

The aim, she says, is to “help us provide shade for our hikers, our clients, and anybody else that goes out there, especially the kids at our dinosaur tracks because right now there are no trees in the desert, there is nothing to protect them.”

The collaboration allowed Kripa and Mueller to create a unique shade structure for the area where Insights promotes STEM education in the border region through a hands-on, fun, and innovative experience.

“We want to be able to provide an educational space for groups and field trips and different things – but make sure it’s safe in El Paso,” Swann says. “Heat is no joke, and the sun is no joke. We want to make sure that there’s a safe shade structure out there that will protect people.”

Built in the style of an amphitheater and made of thin, flat sheets of steel, the dome structure would be able to hold up to 80 children while offering accessibility for wheelchairs. It’s also a sustainable solution, Kripa says: “It can last forever. If they decide to demolish it, they can reuse the steel and melt it. Steel is efficiently recycled.”

Once the prototype is created, it will serve as a blueprint for using similar structures in an urban environment to create shade for the public.

“The prototype is the most complex construction challenge we have: a free-standing long-span shade structure in the middle of a high wind area,” Mueller says. Once the prototype is operational, “we can do different modules, we can make minor adjustments to fit it on different sites that might be even less challenging from structural or even from a design standpoint.”

“I’d love to replicate this in a city where there’s a movement to plant a million trees, but the question is where the water comes from,” Kripa says.

The software and accompanying algorithm created by the duo will be accessible for others to develop the skydomes and learn the shade available in any given area.

“This is for the people and to promote conditions of higher degrees of access to high-quality, safe spaces,” Mueller says. “If this can make it outside the school’s walls and into the community, that would be ideal.”

Christian De Jesus Betancourt is Next City and El Paso Matters' joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellow for Borderland Narratives. He has been a local news reporter since 2012, having worked at the Temple Daily Telegram, Duncan Banner, Lovington Leader and Hobbs News-Sun. He's also worked as a freelance reporter, photographer, restaurant owner and chef. Born and raised in Juarez, El Paso became Betancourt’s home when he moved there in the seventh grade.