In the middle of the Church Hill neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia stands a Greek Revival-style landmark seemingly frozen in time. While churchgoers will pass a few industrial-sized dumpsters anchored upon residential front lawns on the way there, not much has changed at 2800 P St, the site of the neighborhood’s first Black church.

Established in 1859 by 23 enslaved Black Virginians, Fourth Baptist Church is one of the oldest African American congregations in the state. But it’s one wing of the church that caught the attention of a new program to help preserve modern architecture by Black architects and designers.

Added in 1962, the church’s educational wing is a modernist take by Ethel Bailey Furman, the earliest known practicing Black female architect in Virginia and one of the first in the country.

The church recieved a $150,000 grant through the Conserving Black Modernism initiative, launched by The Getty Foundation in collaboration with the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. With it, church leaders and historians aim to repair and preserve the wing and share Furman’s legacy with future generations.

Fourth Baptist Church in Richmond, Virginia.(Photo by Brian Goldstein)

“Our understanding of modernism in the United States will remain incomplete until we recognize the extraordinary contributions of Black architects and designers, whose buildings speak to the experience of Black communities in this era,” Joan Weinstein, director of the Getty Foundation, said in a statement.

“These grants will preserve important sites, deliver training to the people who care for them, and reveal new stories for all of us about the talents and resiliency of Black architects in 20th-century America.”

Eight buildings across the country received funding from the $3.1 million initiative, which seeks to rectify historical oversights regarding buildings crafted by Black architects within modern architecture movement. Getty’s support will include resources towards conservation planning, professional development and storytelling to commemorate and safeguard these structures.

A storied history

Initially meeting in the basement of nearby Leigh Street Baptist Church, Fourth Baptist Church’s enslaved founders reorganized after emancipation and went on to build their own place of worship using wood from nearby abandoned military barracks in Chimborazo Hill. The doors of the current site opened in 1884.

Church leaders have continued to add on to their campus since the late ‘90s, making incremental purchases of surrounding parcels. Today, Fourth Baptist Church owns 2.5 acres of the block, owning everything but a privately-owned convenience store, says James Wallace, church member and historian.

The church has received numerous offers to purchase its property, which it has rebuffed in recognition of its storied history in the neighborhood.

“We lived in this area and grew up in this area,” Wallace says. “We would not only everyone would come here, not only for church service but for other activities during the week. It was the center of the Black community almost.”

Ethel Bailey Furman was the only woman to attend the Hampton Institute’s annual Negro Contractors’ Conference in 1928. (Photo courtesy Ethel Bailey Furman Papers, Library of Virginia)

Among the congregation’s members was architect Ethel Bailey Furman, the daughter of Richmond’s second licensed African American contractor, Madison J. Bailey.

Furman designed an estimated 200 residences and churches throughout Central Virginia, very few of which are still standing today. Among her designs was the Wilder House, the childhood home of Douglas Wilder, who would grow up to become Virginia’s first Black governor.

Prior to her formal architectural training in the 1920s, Furman had already been recruited by her father to work as a draftsperson in his firm. Due to not being allowed to study architecture in Virginia, says architectural historian Brian Goldstein, Furman went to New York to apprentice and then went to Chicago Technical Institute.

Furman would often submit her works under a male colleague to avoid scrutiny and receive approval, historians say. Her designs tended to draw from the modernist movement.

“Modernism was about envisioning a different future,” explains Goldstein, an associate professor of architectural history at Swarthmore College. “It was a very utopian project. It was about building in new ways, new forms, new materials, new scales, with the idea that the world would become better as a result.”

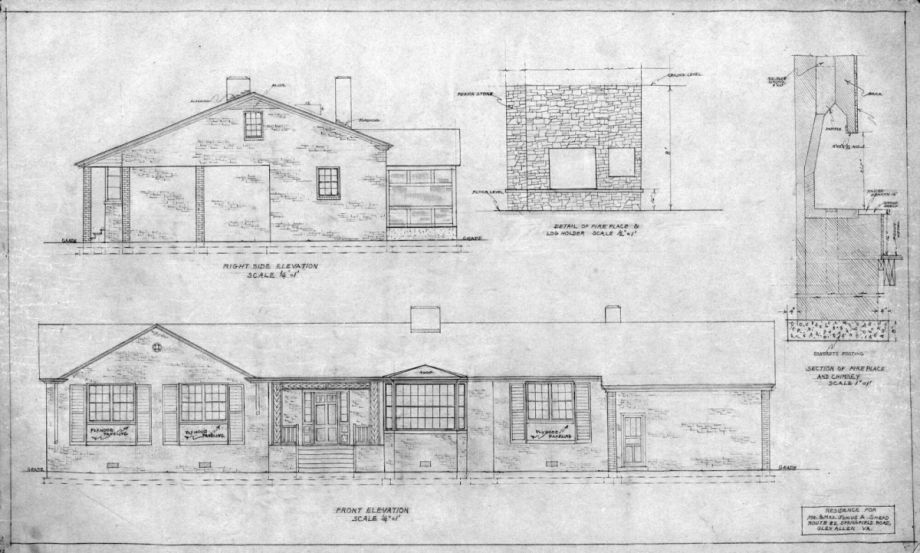

Ethel Furman's architectural sketch of the residence belonging to Mr. and Mrs. Junium A. Snead in Glen Allen, Virginia, date unspecified. (Image courtesy Ethel Bailey Furman Papers at the Library of Virginia)

In many ways, this mirrored the aims of the civil rights movement. “It’s an idea that a new world needs to be built,” Goldstein says. The utopianism of the modernist movement inspired an emerging cadre of Black architects being trained at this time.

But at the same time, he notes, there were real tensions between modernism and minorities.

“A lot of African Americans — and, in general, people who were in a minority status or were seen as others in a global sense — were often at the receiving end of modernism in ways that were very harmful,” says Goldstein, pointing to the urban redevelopment which is seen throughout Richmond.

Around the same time that Furman was working, another Black woman architect in Virginia was also pushing the boundaries of modernism just down the road in Petersburg.

Pioneering Black queer architect and educator Amaza Lee Meredith established the arts department at Virginia State University upon completing her master’s degree and returning to Virginia in 1935. Meredith assumed the role of department chair until her retirement in 1958.

During that time, she designed Azurest South, a residence and workplace for her and her partner, the educator and political activist Edna Meade Colson. Blending self-expression with an appreciation for International Style architecture and avant-garde design, Azurest South has been recognized on the National Register of Historic Properties and the Virginia Register of Historic Resource.

Barry Greene, Jr. is Next City's Equitable Cities Reporting Fellow For Reparations Narratives and a native of Southside Richmond, Virginia. Through his newsletter and moniker “density dad,” Greene is constantly working to spread awareness of the necessity to think of families with young children as well as seniors within the built environment. As a 2023 NACTO Transportation Justice Fellow, Barry aims to help Richmond return to its glory days of leading the industry in public transportation. You can catch him commuting by Brompton, bus or both in conjunction.

Add to the Discussion

Next City sustaining members can comment on our stories. Keep the discussion going! Join our community of engaged members by donating today.

Already a sustaining member? Login here.