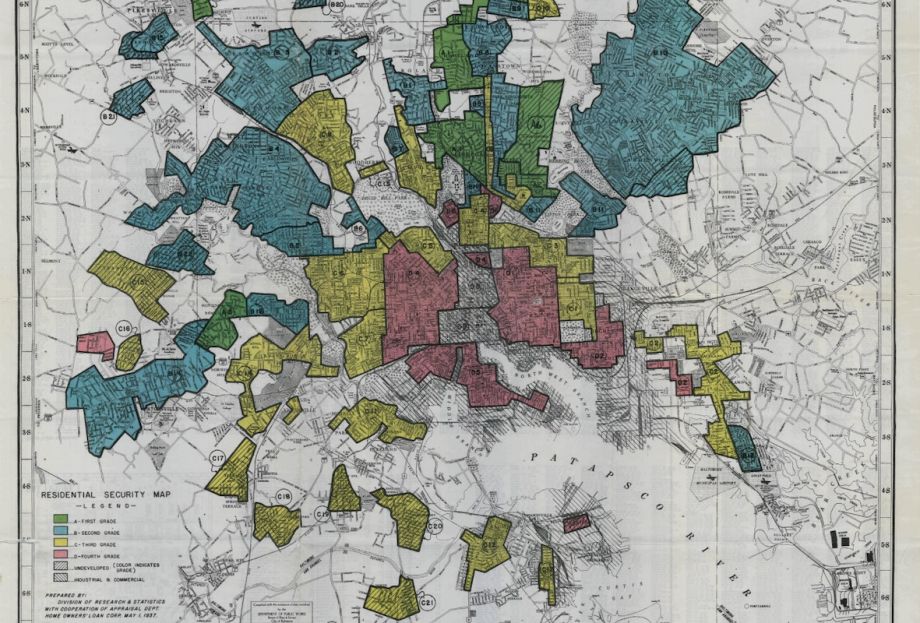

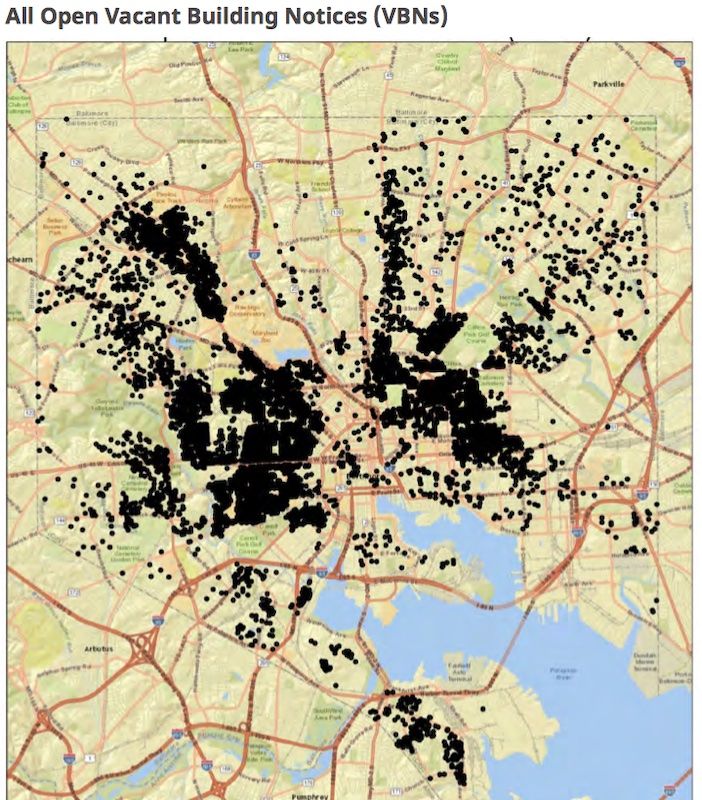

Vacant and blighted properties, boarded up and sometimes stretching for blocks and blocks, are some of the most visible reminders of a time when public policy discouraged lending to neighborhoods where black people lived. Without access to capital to purchase or improve homes, communities gradually fell into disrepair, and many were abandoned. In Baltimore, there’s currently enough housing stock for about a million residents; the city has a population of only 620,000.

Its redlined (and yellow-lined) neighborhoods correspond almost perfectly with the neighborhoods that today have the highest density of vacant properties — more than 16,700 total.

(Credit: Abell Foundation)

After Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake first took office in 2010, the city’s Vacants to Value program was one of the first new initiatives to get off the ground. It’s a multipronged strategy to use data and city resources strategically to fight blight.

Instead of the city acquiring vacant homes and repairing them en masse, Vacants to Value was designed to spur the private sector to do the work using a carrot-and-stick model: providing a range of incentives for new private investment, while also ramping up code enforcement on negligent, largely absentee landlords and deploying strategic demolition of blocks in particular disrepair.

One of the unexpected pillars of the program has been the city putting properties into receivership, obtaining court orders to force owners to make repairs or auction off properties to a new private owner. Before 2010, the city never filed more than 100 receivership cases in a year; in the first four years of the program, the city filed 1,876 lawsuits against private property owners, according to a report from the Baltimore-based Abell Foundation.

Whether by receivership auctions or disposition of city-owned property (sometimes taken by eminent domain), private developers from Baltimore have been active in purchasing and rehabbing properties.

One of them has been City Life Builders, a Baltimore-based developer that has been renovating properties in East Baltimore since the early 1980s, investing more than $31.5 million in historic rowhome renovation.

At a Reclaiming Vacant Properties conference in September in Baltimore, City Life touted city incentives to homebuyers as a key driver for their work, such as the Vacants to Value Booster program, which provides $10,000 for down payment and closing cost assistance for people buying a formerly vacant, renovated house. By providing some assurance of an end-market, buyer incentives can help developers access upfront financing to rehab homes.

According to the Abell Foundation report, The Dominion Group, also based in Baltimore, purchased at least eight homes out of receivership, selling some of them to homebuyers using Vacants to Value Booster grants.

The Abell Foundation report concluded that the program was dependable for identifying and cracking down on owners of derelict houses in scarred neighborhoods, with signs of success in a few long-neglected neighborhoods. But reviews remain mixed, overall.

One activist in East Baltimore told the Abell Foundation that he wrote to city officials complaining that Vacants to Value’s practice of selling city-owned houses to for-profit developers “does not coincide with creating or maintaining affordable housing for the majority of the … current residents.” There are no stipulations on affordability for private developers purchasing homes out of receivership in Vacants to Value.Development of vacant properties has also been uneven, the report found, with some neighborhoods attracting more development than others. Vacant building notices officially went down from 2010 to 2014 in the Greenmount West and Oliver neighborhoods, for example, while the city overall saw a rise in vacant building notices. Oliver, home to at least one community-oriented for-profit developer, saw the most vacant properties put back on the market out of any neighborhood over that period.

Also, according to the report, by far the most successful developer of Vacants to Value houses has been a non-Baltimore developer, the Philadelphia-based Reinvestment Fund, a community development financial institution (CDFI).

Focusing on the Oliver neighborhood, Reinvestment Fund created a dedicated fund of $10 million, from 40 different investors, including such diverse donors as the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Jewish Funds for Justice, M&T Bank, T. Rowe Price Foundation, Rosedale Federal Savings Bank, the Rouse Company Foundation, the Archdiocese of Baltimore, the Joseph Meyerhoff Fund, and the College of Notre Dame. The CDFI also obtained $1.6 million in federal stimulus funds to help restore 38 properties.

As of early 2015, Reinvestment Fund had completed more than 230 housing units in Oliver and had another 100 in its pipeline. But, to its credit, Reinvestment Fund first came to Baltimore in 2008, two years before the Vacants to Value program. As the Abell Foundation report notes, it’s not always clear, other than in cases of receivership or Booster grants, how much of a dent in vacant Baltimore homes can be attributed to the Vacants to Value.

Only 360 Baltimore homebuyers have benefited from Vacants to Value Booster grants so far, but Rawlings-Blake announced additional funding for the program earlier this fall.

This article is one in a 10-part series about reclaiming vacant properties underwritten by the Center for Community Progress. Read more here.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)