This story was originally published in Baltimore Beat, a Black-led, Black-controlled nonprofit newspaper and media outlet.

For the Eaddys, their home, located in the Poppleton neighborhood, means roots—a place that family can go. Sonia Eaddy said that her grandson, who just got out of school, is staying with her now, in this four-bedroom home tucked into a quiet corner of West Baltimore.

“It’s always somebody here,” she said. “This is our family home.”

It is a place she and her husband Curtis created to suit their wants and needs. A house transformed into a home over 30 years of hard work. First, they opened up the living room and dining room to make the space more welcoming and airy; then, they added a first floor bathroom. After a fire in 2012, they finished the basement.

For them, the 319 North Carrollton Street home isn’t just an address on the map, it is the sum total of hard work and determination.

“I was sitting in this living room and I would dream,” she said. “I would sit here and say, ‘I would love to tear that wall out.’”

But to the powers that be, this place in a neighborhood battered by disinvestment was nothing more than brick, concrete, wood, and metal: a point on a map, a means to an end, or something that needed to be demolished to make way for progress. The people who saw the property as just a house likely didn’t know much about who lived inside, but they soon would.

The Eaddys had been in their home for more than a decade when trouble came knocking at their door. Residents of Poppleton learned about plans for their community in 2004, at a town hall led by community stakeholders including the University of Maryland and representatives for the city, then led by Mayor Martin O’Malley.

New York-based company La Cité planned to develop 13.8 acres of the Poppleton neighborhood and build 1,800 housing units and 250,000 square feet of commercial space over the course of 20 years.

Officials used the term “eminent domain” but didn’t really explain to Eaddy and others what it meant. Homeowners were told they would be given “fair market value” for their houses. Renters were told they would get the equivalent of five years’ rent if they left, which in some cases was more money than homeowners would have received from the city if they chose to leave.

Baltimore’s housing market has historically reflected the segregation and racism woven into the city’s past and present. A home in a mostly Black neighborhood wasn’t valued as highly as homes in places like Hampden or Locust Point, where working class whites could sell theirs for much higher returns.

“In the inner city, not just Poppleton…in Black neighborhoods, property values weren’t anything at that time,” Eaddy said.

At the time, she believed that the city wanted to use eminent domain to take homes in Poppleton. But eminent domain is when private land is taken for public good. If her land was being taken for use by a private development company, how did that fit? She couldn’t understand why her community had been targeted.

The community had changed for the better since the Eaddys acquired their home in 1992. Community members got together to build a park and made their presence known to neighborhood drug dealers, many of whom packed up and left because of the attention mothers, fathers, grandmothers, aunts, and uncles were bringing to their trade.

“This wasn’t a block of dilapidated homes. This wasn’t a block that had vacancies. This was a vibrant block of all age groups—we had a lot of seniors, we had a lot of little kids—and people began to sit out on the front again, interacting with one another,” Eaddy said.

A Black-run city like Baltimore does not mean that all Black people are protected. Eaddy says that even though the people behind Black-owned development company La Cité such as Dan Bythewood Jr., look like her, they don’t share common goals. Members of the Poppleton Village Community Association, business owners, and pastors joined local politicians in siding with the developers, and urged Eaddy to shut up and take the buy-out. Even Eaddy’s own delegate tried to sell her on the deal. “This is a win-win for everybody,” people told her.

“I needed them to understand that the land is not about your house, it’s about the land that your house is set on,” she said. “Your land is valuable.”

Eaddy took stock of the power imbalance and started her own homeowners association. She built the association in the same way you’d run for office—by knocking on doors and finding like minded neighbors who didn’t like how things were going and wanted to work together to bring about change.

“I had to get out there and find out who the homeowners were and invite them out to the meetings,” she said. “And I was surprised people showed up.”

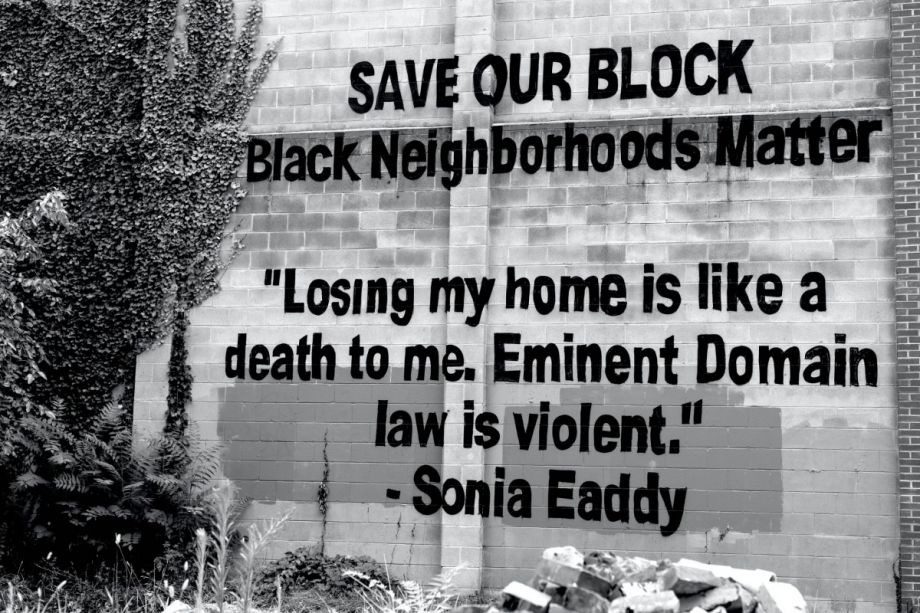

Mural on the side of Sonia Eaddy’s home (Photo by Cameron Snell / Baltimore Beat)

The first thing members did was identify what they wanted. Some people wanted to move, and so for them, the priority was getting them the most money possible to relocate. She and the other members quickly saw the power that came in unity.

There were a few reasons why some residents were eager to leave. Some were older, and a house was a lot for them to maintain. Something like a senior high rise made more sense for them. But Eaddy also explained that once city officials and developers set their eyes on Poppleton, they didn’t make it an easy place for residents to stay.

“You tore down houses and left vacant lots,” she said. “The city isn’t managing anything.”

Eaddy explained that trash accumulated, along with high grass.

“We are homeowners, we don’t want to live like this. I didn’t buy my house to live like this,” she said.

Eaddy said that the group together was able to negotiate more money for homeowners who were leaving, which she calls a win. Still, she thinks if they had known more at that time, they could have fought harder, sooner.

“[The city and developer] played off our ignorance,” she said. “I had to get a lawyer and the lawyer asked me ‘Why didn’t y’all just do a class action suit?’ Nobody knew!”

Meanwhile, the development ran into obstacles with financing and then a legal battle with the city. This bought Sonia time. She began researching, learning everything she could about the subject of eminent domain. At the same time, the city was moving to take her home, so she hired a lawyer who specialized in these issues. She learned that it’s extremely difficult to win an eminent domain lawsuit. The best homeowners could hope for was more money for relocation. Eaddy wasn’t interested in a higher payout. She wanted her home.

“I want to fight the law,” she says she told the lawyer. “I’m here to fight the eminent domain law for the state of Maryland, for the city of Baltimore, because what they are doing when I’m studying eminent domain, it doesn’t match up to what Baltimore City is using eminent domain for.”

The Eaddys activated, along with residents whose homes were also threatened or had been already taken due to the redevelopment. They put pressure on the city and they made the name of the developer known. Eaddy had a 20-foot high message painted on the side of her beloved home that said, “SAVE OUR BLOCK. Black Neighborhoods Matter. Losing my home is like a death to me. Eminent Domain law is violent.” When city officials toured Poppleton last year, residents pointed to how stalled development had made their neighborhood worse and Eaddy told them, “We were sold out…I love my house.”

On July 18, 2022, the city announced that the Eaddys’ home would no longer be part of the redevelopment plan. It was an unprecedented win nearly 20 years in the making. The city also negotiated to have the colorful Sarah Ann Street alley houses taken out of La Cité plans for Poppleton. These historic homes have not only been saved from likely being demolished, but will be rehabilitated by local group, Black Women Build- Baltimore.

“They kept saying eminent domain is unbeatable,” Eaddy said at the July press conference. “But this is proof today. If you stay, if you don’t give up, anything is possible.”

Weeks before the city announced that she would be able to keep her home, Eaddy was confident that she would not have to go, unless she herself chose to move. “There have been so many mistakes made on behalf of the city,” she said then. “And the developer cannot make this thing happen.”

Also, Eaddy says, Mayor Brandon Scott talked big about progress and prioritizing Black Baltimore when he was running for office. This boondoggle was an opportunity for him to turn his words into actions.

“You ran on some things,” she said, speaking about Scott. “You talked about the Highway to Nowhere, in making reparations to those people. How can you do this and you displace me? How does that fare in the media?”

Eaddy says that her fight is not over. She has a bigger foe ahead of her than a developer or even the city of Baltimore: harmful eminent domain laws. She says that these laws are used to steal not just Black homes, but Black lives and Black histories.

“Where eminent domain is being used is in the Black neighborhoods and so, our history is being erased,” she said.

Eaddy says that even if she had lost the fight for her home, it would’ve been worth it because she now knows that the practice of taking homes through eminent domain must end.

“I believe that it was God having me here to bring this awareness,” she said.