Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberWallace Wyche is tending shop in a ghost town. The three-block-long shopping mall where he works in the heart of Philadelphia is empty, cleared out for a massive renovation. At one end, where his Verizon store is situated, a few stragglers hang on: a leather goods shop, a perfume shop, a GameStop. A lone police officer sits at a security station, clearly bored out of his mind, and looks over the empty expanse. There used to be two cops stationed here, but the second was taken off the desk.

The scene is a far cry from the mall where Wyche first began working. Then, The Gallery at Market East, known as “The Gallery,” was bustling with people, many of them black and coming from neighborhoods that didn’t have a lot of safe places to meet a friend, pick up new shoes or grab a bite to eat.

For the past 15 years at least, The Gallery has been what Elijah Anderson, a Yale professor of sociology, calls “a black place,” attracting a majority African-American clientele from the city’s disinvested North and West sections — both a mere subway or trolley ride away.

But last year, the owners of the mall, Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust (PREIT), began to reinvent the mall for a new clientele. Now riot screens cover the tunnels connecting the mall’s subterranean eastern and western halves. The crowds have vanished, along with the numerous shops frequented by black shoppers, like Horizon Books, one of the last African-American bookstores in the city.

“A lot of people who can afford to are moving in [to Center City],” says Wyche, 28, who is African-American and lives about 10 miles away in the city’s Mayfair section. Of the owners of The Gallery, he speculates, “I think they are trying for a different tax bracket. They are weeding out the people who can’t afford to shop that high.”

New mixed-use towers that will include offices and luxury apartment are under construction on the blocks surrounding The Gallery.

Today, Center City Philadelphia is the second most populous downtown in the country, a dense, transit-friendly hub where a good meal and plenty of shopping options, from posh Barneys New York to cheap-chic Buffalo Exchange, can be found on foot. For the first time in generations, people are moving downtown, to luxury apartments and condos being created above and alongside fancy restaurants and chain retailers that are no longer afraid of the city. On Market Street east of City Hall, a prime stretch connecting the city’s business center to Independence Mall and other tourist attractions in Old City, it isn’t only The Gallery (now the Fashion Outlets of Philadelphia) that is getting a facelift. There are at least two other major mixed-use projects underway, and many smaller developments, which promise to add thousands of new apartments and hundreds of thousands of square feet in new commercial space. Even before those projects are complete, the population of what the Center City District terms “Greater Center City” had, at last count, grown by 17 percent (since 2000), largely driven by an influx of childless millennials and empty nesters.

But outside of Center City and its halo of revitalizing neighborhoods, Philadelphia still struggles with crushing poverty — more than a quarter of the city’s population lives under the poverty line — and middle-class flight. Although the unemployment rate in 2015 fell to 7 percent, there are still many parts of North and West Philadelphia where it is more than twice that. A 2015 Pew analysis found that in a ranking of comparable cities, only Detroit has a larger share of its population outside of the labor force. And while some centrally located areas are gentrifying, many outlying middle-class neighborhoods have seen median incomes drop precipitously.

Depending on whom you ask, The Gallery was either one of the few Center City amenities serving the city’s working-class and lower-income majority population, or a throwback to a time when even the most choice Philly real estate could rarely attract the most desirable tenants. (A Kmart served as one of the mall’s anchors until it closed in 2014.)

Shoppers ride the escalators in The Gallery's central atrium in 1981. (Credit: Prentice Cole/ Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives)

And while PREIT is keeping quiet about which retailers it is courting for the revamped space, the company clearly hopes to shed the mall’s discount store vibe. Renderings show a brightly lit, glass-fronted structure with sit-down restaurants and shops facing out to the street. In an emailed statement, PREIT spokesperson Ashlyn Delson describes the new offerings as “a fusion of outlet retail including designer and moderate brands, popular flagship retail, artisanal food experiences and entertainment offerings.” She calls it “the future of outlet retailing.” Still, the first new tenant PREIT has welcomed is a Century 21, a discount retailer of designer clothing.

But as Center City continues to grow and neighborhoods on the city’s fringe continue to stagnate, it is worth asking whether the mall can remain a diverse hub for all Philadelphians now that its lower-end corners are being upgraded. It isn’t only The Gallery, after all, that is moving upmarket. Chinatown is being transformed by an influx of wealthy single professionals (many of them Chinese), while the area known as the Gayborhood has shed all the trappings of its past as an affordable — if seedy — respite for the young and queer and now boasts a nationally renowned concentration of high-end restaurants. Earlier this year, the central Love Park closed for a complete rehabilitation that will transform the austere modernist plaza — which attracted a steady stream of skateboarders, many from lower-income neighborhoods — into a greener and more tourist-friendly site. The old Dilworth Plaza outside City Hall is long gone too. Once a grimy warren of bizarre little alcoves, which sheltered Occupy Philly and a year-round homeless population, it is now a sleek, well-secured monument to the new Center City, all fountains and open space where encampments once stood.

Changes of this nature are probably inevitable. A booming downtown will not long cede swaths of prime real estate to uses that predominantly attract low-income people. But we shouldn’t pretend that nothing has been lost in the transformation of these spaces or that the people who frequented the old Gallery or Love Park will necessarily be back.

“I don’t know if it can be all things to all people,” says Inga Saffron, the architecture critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer. “The Gallery was an amazing space, like a town square, where a lot of people came together. Will it be like that again? I don’t know. Can it be both things? Probably not.”

But these are emotional, perhaps academic questions. In a city that is still losing middle-class residents from its outlying neighborhoods, and isn’t likely to receive much aid from Harrisburg or D.C., the growth of Center City is a rare success story. And gentrifying a shopping center is very different than gentrifying a residential neighborhood, which is in itself different than privatizing a public space. The Gallery may have been making money, but if it could be making more money, with its environs attracting more residents, perhaps that wouldn’t only be good for the developers.

“We need to keep pumping up our tax base and Center City is absolutely wonderful [for that],” says Alan Greenberger, former Mayor Michael Nutter’s deputy mayor for economic development and director of commerce for the city of Philadelphia between 2009 and 2015. “That means more consumer activity, more people living there with the means to buy something, more offices. That means a broader and deeper tax base, which can support the city as a whole. We have to make the successful stuff really work hard.”

From the floor of the now deserted Gallery, this vision can be a little hard to appreciate. Just last year, the food court was still playing its role as an impromptu gathering space for elderly people from the neighborhoods, the kind of safe public space that is too rare in many tracts of the city. (“‘This is better than the hood,’” Anderson reported one old man saying in his 2011 book, The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Every Day Life. “‘I ain’t got to worry about being shot at.’”) The lower two floors still swarmed with shoppers, echoing with laughter of teenagers freed from school for the day. The upper stories weren’t profitable, but research seems to show that they aren’t profitable in most urban malls.

In his empty Verizon store, Wyche considers whether there is another place in Center City that can serve the same function that The Gallery did for lower-income and working-class people. “There’s not really another centrally located space where people can do a lot of things,” says Wyche. “The short answer is no, not downtown, not that I know of.”

This current revitalization crusade isn’t the first that Philadelphia’s eastern section of Market Street has experienced. The Gallery is the hulking result of the first effort to bring life back to what had been the commercial heart of the city since 1874, when John Wanamaker transformed an old freight railway depot into an iconic department store. In the decades that followed, eight imitators staked their claims in the same area, transforming this corner of the city and sparking an arms race of conveniences and bargains that drew ever greater crowds.

As the 20th century wore on, the vitality of the retail giants was sapped by a multiplicity of factors, not least of all the suburbanization of the region’s population and economy. Even before the Depression, four major department stores had faded away. By 1977, with only a few of the old department stores remaining and racist fears of the city propelling an ever larger shift of capital and people into the suburbs, local policymakers and civic leaders unveiled their Hail Mary: a huge windowless mall sealed off from the city outside and given the aspirational name of The Gallery.

The result was one of those mid-20th-century megaprojects that many cities threw up during the urban crisis in an attempt to stem middle-class flight and bring consumer dollars back downtown. Stimulated by nearby commuter rail lines, the mall, for a while, succeeded in Philadelphia in a way that such efforts did not in, say, Cleveland. Early reports found sales that were double or triple the expected $100 per square foot that the mall’s developers had expected. One hundred and twenty-five shops and restaurants, including four with liquor licenses, were packed into the space. At the end of 1977, one report found that the mall’s sales were outstripping any of its regional suburban counterparts at $250 a square foot — over $913 in today’s dollars. By point of comparison, the tony, suburban King of Prussia Mall today commands about $700 a square foot.

But from the beginning, The Gallery was criticized for sucking energy and pedestrians from the surrounding streets. The critics had a point. “Here, in effect, we’re building a suburban mall on a downtown site,” the head of construction, W. Scott Toombs, told reporters before it opened. Nearby merchants saw traffic slow, and gradually higher-end retailers left, to be replaced by cheaper tenants or vacancies.

As it turned out, The Gallery would not maintain its lock on shoppers for long. After an initial burst of excitement, the mall’s owners had a hard time getting the high-end merchants it had envisioned for the glass and steel structure and instead, filled the space with mid- to low-market chain outlets. By the 1980s, The Gallery was a popular destination for black Philadelphia, earning a name check in D.J. Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince’s 1988 hit “Parents Just Don’t Understand,” and offering an unusually robust “black studies” section in the chain bookstore on the mall’s concourse level.

“The Gallery was a safe space. It was a social space. It was the mall kids went to go on dates in high school,” remembers Omar Woodard, executive director of GreenLight Fund, a Philadelphia investment firm for low-income communities. He grew up in North Philadelphia in the 1980s and ’90s and recalls heading to The Gallery every other day in high school, meeting girls there, even helping a friend sell oils and incense in the concourse. “It was incredibly democratic in terms of a business place. You had people selling earrings, watches, attire, but you also had upscale stuff. For African-American people especially, The Gallery was a safe space.”

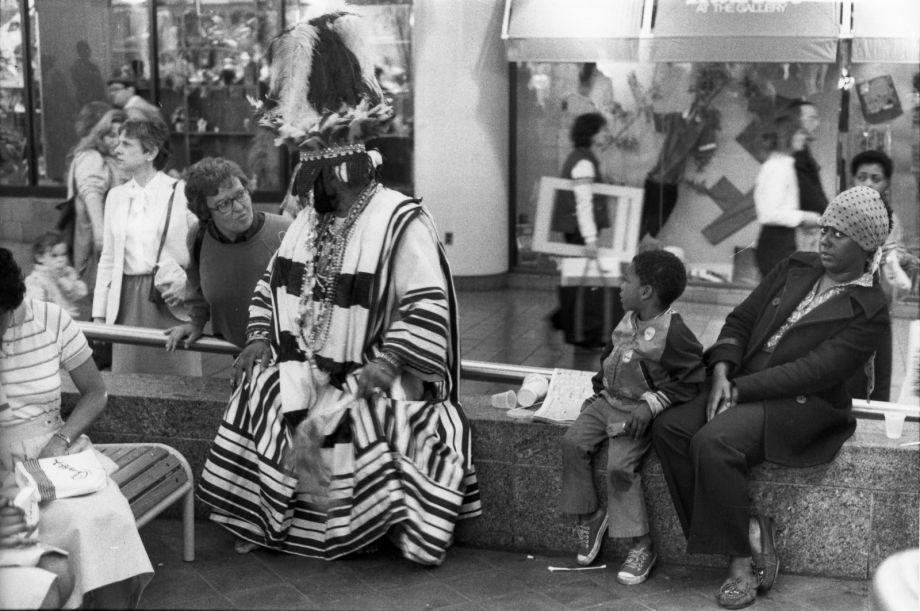

A Philadelphia man dressed as the High Chief Priest of Nigeria chats with shoppers at Urban League Day at The Gallery in 1984. (Credit: Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives)

As the decades wore on, the allure to white Philadelphia, or to the middle and upper classes of any race, almost completely faded as the building aged and Center City emerged as one of the most successful downtown revitalizations in America.

Anderson lived for many years in Philadelphia, raising a family there, teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, and studying the way race and class play out in everyday urban life. His observations come to life in The Cosmopolitan Canopy, named for the all-too-rare spaces that attract people across racial, ethnic and economic lines and encourage “civility across racial lines.” Anderson contrasts The Gallery with Central Park-like Rittenhouse Square and Reading Terminal Market, a bustling indoor food bazaar located next door to the Gallery.

Eljah Anderson describes Reading Terminal as a “cosmopolitan canopy,” attracting a divese spectrum of people and encouraging “civility” across difference.

Those places, thriving and diverse, he argues, exemplify the cosmopolitan canopy while The Gallery evokes a phenomenon he describes as “the iconic ghetto.”

“The Gallery was the iconic ghetto downtown,” Anderson says. While the term refers to the way white America imagines spaces inhabited by African-Americans as dangerous and threatening, Anderson lovingly describes the lively social scene in and around The Gallery. Outside, street vendors sell jewelry, African garb, incense and, occasionally, drugs. The reader is left with an impression of a busy, warm, communal environment. Anderson repeatedly notes that the mall served much the same function that black neighborhoods did before so many of them were hollowed out by urban renewal and wracked by gun violence.

“There’s no place you find blacks as concentrated [in Center City] to the extent they were at The Gallery,” remembers Anderson, who spent months hanging out in the mall, learning its rhythms, wandering its hallways and drinking coffee with a group of older African-American men who held court in the food court. “I do worry that you have people who used to be able to go there and be free, black people from the neighborhoods, who will no longer have a place to be there. It was their place. They could relax there, like a home away from home. It was very pleasant. I loved that place.”

Throughout all this, the property was still profitable, but prices didn’t quite keep up with inflation. In 2014, it was making about $327 a square foot. Still, that’s not too shabby in the age of Walmart and online shopping, when many malls are suffering and closing entirely.

“The sales volumes in there were great,” says Paul Levy, Center City District executive director. “Don’t let anyone tell you it was failing. But it was a street killer on the outside.”

PREIT’s plans promise to reconnect the shopping center with the rest of Market Street. In 2014, the real estate company brought in Macerich, the third-largest publicly traded mall company in America, which now has a 50 percent interest in The Gallery. Construction is estimated to take at least two years, and completion is expected in late 2018 or early 2019.

Woodard has mixed feelings about the project, which he views as a necessary auxiliary to the Pennsylvania Convention Center and the luxury hotels that have sprouted near City Hall. Although he loved The Gallery as it was, he also recognizes that it proved a challenge. Its stores did not appeal to conventioneers and tourists, and the closest shopping destinations were around Rittenhouse Square, a mile away from the convention center. It didn’t compare to the outlet offerings that similarly prominent cities like Atlanta or Boston have in their city centers to capture tourist dollars. The population that could be served in the immediate vicinity had changed radically as well. In 1980 there were only 2,768 people per square mile in the census tract that contains The Gallery. By 2000, there were 6,762. At last count, the number had more than doubled to 14,424 with similar patterns in most of the surrounding tracts.

“They’re basically swapping out one demographic to bring in another because the other wasn’t there 25 years ago,” says Woodard, looking back to the days before the convention center opened. “To maximize The Gallery’s asset value, you have to redo it, and PREIT and others have made the decision that we want this to serve a certain type of customer. It’s like gentrification in the retail space, but it’s also different than in a neighborhood because retail space isn’t as democratic. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t losers.”

Beyond The Gallery’s total rehabilitation, almost $1 billion is primed to be spent on East Market Street. It’s the kind of concentrated attention from numerous market actors that did not accompany The Gallery’s initial construction.

In addition to hundreds of new apartments planned throughout the area, Brickstone Companies is sinking tens of millions into the rehabilitation of a series of dingy properties at 11th and Market, which it plans to convert into space for offices, apartments, a two-story restaurant and a Target. The National Real Estate Development company is working on a $500 million complex near The Gallery, which will contain a MOM’s Organic Market and two apartment towers. Smaller investments are being made by a small scrum of other companies, all of which are expected to increase the area’s residential and pedestrian population dramatically.

“This is where there is opportunity,” says Steven Gartner, executive vice president for retail services at CBRE, a commercial real estate services provider. “I mean, my gosh, this is not on the edge of town. This isn’t Port Richmond, this is the heart of town where there is an aberration and a big opportunity.”

In five years it will probably no longer be possible to purchase off-brand sneakers or get your hair braided on Market Street. In this, the area will share the fate of the Fulton Mall in downtown Brooklyn. That area began life as a genteel retail center but as Brooklyn’s fortunes and middle-class people left the borough, its shops drifted down market and began catering to the people who had actually stayed in the area, chiefly the African-American working-class.

But that didn’t mean it wasn’t successful. Again, like The Gallery, Fulton Mall made money. Its streets were packed day in and day out, in large part because the shopping district sat at the intersection of six subway lines, making it accessible to hundreds of thousands of Brooklynites without cars. Discount electronics and clothing stores thrived amid a lively street vendor trade. Authors sold slim, paperback volumes of urban fiction and entrepreneurs sold gold caps. But as Brooklyn revitalized with a vengeance, these offerings looked increasingly out of sync with their immediate surroundings. Until, at least, Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration rezoned the area in 2004, kicking off the in-migration of glassy office towers, luxury apartments and big retailers like H&M. The funky boutiques and bodegas began to close. After 10 years of transformation, Fulton Street’s retail footprint now looks a lot more like Midtown Manhattan or the shopping district around Philadelphia’s tony Rittenhouse Square.

“It’s really hard with a commercial space because tenants don’t have a lot of rights and the people who shop there don’t live there, so it’s hard to organize them,” says Kelly Anderson, a documentarian who made a film about Fulton Mall’s remaking and the erasure of its old form. “This idea of the space not keeping pace with the gentrification of the surrounding neighborhood is very similar … . I just don’t get why every urban space has to look exactly the same as every other one.”

It’s undeniable that when all of the development on Market Street is complete, The Gallery and its surrounding blocks will look very different. Yet just as Fulton Mall remains a more diverse place than other nearby Brooklyn shopping corridors, still able to attract many of its former denizens, the social space Anderson wrote about is unlikely to completely disappear, and PREIT has already promised that the old pushcart vendors can have a place in the new mall.

The Gallery will likely no longer be the “iconic ghetto” downtown but it may yet become one of Anderson’s cosmopolitan canopies. Philadelphia, after all, remains a diverse city and the mall itself still sits at the heart of a large transit system, a mere $2.75 ride away from neighborhoods that continue to offer little in the way of safe public space and retail. As Anderson puts it, The Gallery wasn’t intended to become the place it ultimately became. “There’s a sense in which you couldn’t plan The Gallery and have it be the way it was, there was something peculiarly organic about it,” he says. “These spaces aren’t organized. They move and change on their own and they happen quite organically.”

Another variable is the cyclopean hull of The Gallery itself. The entire promise of the Fashion Outlets at Market East is that they will do away with the ’70s-era form and replace it with a New Urbanist ideal: umbrellas on the sidewalk, pedestrians peering through the windows, life flowing easily from the mall to the street and back. But as Inga Saffron has pointed out in The Inquirer, the transformation may not be possible. Much of the mall’s frontage along Market Street is devoted to fire doors, which cannot be replaced with windows or storefronts, and apparently contain much transit infrastructure connected to the station below. As a result, long stretches along Market and Filbert streets are likely to remain inert.

“I’m sure PREIT would have liked to tear the entire thing down and restart it from scratch, but that would have cost a lot of money,” says CBRE’s Gartner. “I hear they are talking to a lot of tenants all over the country, many of which would be unique to the market and first time here. … Failure is not an option for them. They have to do this. Even if they have to give away cheap rent, they are going to have to pull it off.”

Back in the withered rump end of The Gallery, Rahshan Hennigan, 24, of West Philly is hanging out in the GameStop, remembering the mall as it used to be and keeping his fingers crossed about its future.

“The food court was always packed, even at nighttime it was packed, because people want to sit and just chill,” Hennigan says. “Then you could shop for cheap. I got my wallet here, my shirts, my hats. … I hope something good comes out of [the renovation]. Something I can use. In here, it used to be, you could sit and stay for a while.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Paul Gargagliano is a Philadelphia-based freelance photographer. Brooklyn born and bred, he studied photography at Oberlin College. His work ranges from photojournalism with an urban bent, to wedding and event photography with Hazelphoto.com.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine