Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Liza Katz thought she’d be living her life abroad. She majored in international relations and her graduate work was in international economic development. She spent a year in Buenos Aires focusing on policy, a month teaching statistical analysis at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, and a semester studying the Velvet Revolution, which included a trip to the Czech Republic. “I always picked an international focus because of the allure of overseas,” she said.

But in the end, the globetrotting Katz found herself right back where she began: Michigan. The trick was to bring the globe to the Wolverine State. Or a bit of it, anyway.

I met Katz at a reception, hosted by the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF), at The Whitney, a magisterial mansion-turned-upscale restaurant in Detroit, once the home of a timber baron. David Whitney built the 52-room house on Woodward Avenue in the late 19th century, at a time when Michigan was the nation’s leading lumber producer. The state held claim to that mantle for more than 30 years. But several serious forest fires and the rise of mining meant that 1900, the same year Whitney died, was the last time Michigan stood at the peak of lumber production.

Michigan, of course, is no longer a stranger to dominating an industry and then declining along with it. Its top-of-the-hill position in car manufacturing during the 20th century led to a dependence that hit the state with a far longer recession than that experienced by the rest of the country. The Whitney sits on Motor City’s main corridor, which bears the first paved mile of roadway in the U.S. and came to host the heart of cruising culture along its wide lanes. Now, the patchiness of the Whitney’s neighborhood reveals the uneven latter-day history of yet another leading Michigan industry.

A month after General Motors and Chrysler filed for bankruptcy in summer 2009, Michigan’s unemployment rate tipped over 15 percent. It has improved in the years since — it hovers around 9 percent these days — but it consistently tops the national average. One in five African-American workers are unemployed in Michigan, the highest rate in the nation and 2.5 times higher than white workers in the state. In the final quarter of 2012, unemployment among black Michiganders was 18.7 percent, compared to 14 percent nationally. Many of these out-of-work residents, of course, are the children and grandchildren of those who came to Detroit during the Great Migration to work at famously well-paying car factories.

It is surprising, then, that Katz came back to Michigan in 2003 for work. More than that, her job is to help others find work. “The biggest myth about jobs in Michigan is that there are none,” she told me in the Ghost Bar at the Whitney.

Katz spent eight years working for the Detroit Regional Chamber and the Corporation for a Skilled Workforce before founding the Workforce Intelligence Network, a consortium with the not-incidental acronym of WIN. Seven Michigan Works! agencies — employment centers located around the state — and eight community colleges make up the network, an active collaboration designed to knit together the disconnect between the unemployed and open jobs going unfilled in a nine-county southeast Michigan region, which includes hard-hit cities like Detroit, Flint and Pontiac. WIN was founded in 2011 at the high of the recession’s impact on the state.

“Right now, countries like Germany focus on graduating their high school students with the equivalent of a technical degree from one of our community colleges, so that they’re ready for a job.”

High unemployment and underemployment notwithstanding, there are tens of thousands of unfilled jobs in Michigan. The trouble is, they don’t necessarily match the skill sets of the potentially employed, and a great deal of workforce training opportunities are trumped up and ineffective, failing to lead to jobs for participants even when jobs are available. Leaving aside specialty sectors that are in demand of employees with advanced degrees — computer programmers, engineers, and primary care physicians and nurses are in demand — mid-level positions are bountiful in Michigan and beyond. This includes dental hygienists, electricians and production machinists in high-tech manufacturing labs.

The skills gap in Michigan is not unique: President Obama acknowledged it as a nationwide issue when he urged an expansion of vocational education in his State of the Union speech in January. He highlighted P-TECH in Brooklyn, which provides students with a combined high school diploma and associate’s degree in a high-tech field when they complete six years of study and externships. (Greg Lindsay explored the P-TECH model in an August Forefront story.) This picks up on the push by Obama and Education Secretary Arne Duncan for post-secondary technical training as a serious and viable alternative to four-year colleges. The idea is for 21st-century vocational education not to track kids perceived as too dim-witted to cope with college for jobs with limited growth that risk extinction as technology evolves. Rather, the new kind of vocational education would focus on a host of diverse careers, where learning takes the form of applied skills and real-world impact.

In his speech, Obama also announced the new network of regional institutes promoting manufacturing, the first of which opened last year in Youngstown, Ohio. (I wrote in depth about these institutes in a previous Forefront story.) These institutes are not created in a vacuum: Pushing back against common notions, manufacturing represented 37 percent of job growth in the United States between 2009 — the year GM and Chrysler filed for bankruptcy — and 2012, according to Rebecca Blank, U.S. deputy secretary of commerce. Moreover, manufacturing jobs pay an average of 17 percent more than in comparable sectors. And yet, even as national unemployment flirts with 9 percent, there are about 600,000 open manufacturing jobs in the United States, about 5 percent of the sector’s total jobs.

That’s why eyes are turning to Germany’s vocational training system. “Right now, countries like Germany focus on graduating their high school students with the equivalent of a technical degree from one of our community colleges, so that they’re ready for a job,” Obama said.

Lisa Katz, too, is borrowing from Germany’s model to connect Michigan workers with jobs using data-driven support — not only for the sake of people in need of work, but for the sake of companies starved for skilled employees. At GMF’s invitation, she traveled to Germany to study its famed “dual track” vocational education model, and is applying much what she’s seen to programs training workers in Michigan’s populous southeast corner. Meanwhile, the state is launching the pilot phase of a major vocational program that brings employers and community colleges together to provide select students with rigorous (and stipended) study, paid work and a guaranteed job upon completion. It is explicitly modeled on Germany’s approach.

This is more that an intercultural public relations experiment between the Midwest and Germany. Real lives are on the line, as is the ability of Michigan cities to sustain stable economies, like Hamtramck, a bustling immigrant community flirting with emergency management, like neighboring Detroit, which it borders on all four sides.

Often, the prescription for struggling cities is “more jobs.” But what about the unfilled jobs already there? “Billions and billions of dollars are going into creating the workforce of the future,” said Amy Cell, senior vice president for talent enhancement at the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, a public-private partnership. But what does it take to do workforce training well enough that it actually gets people to work? And is it true that the best map to connect Michigan workers with those jobs drawn more than 4,000 miles away?

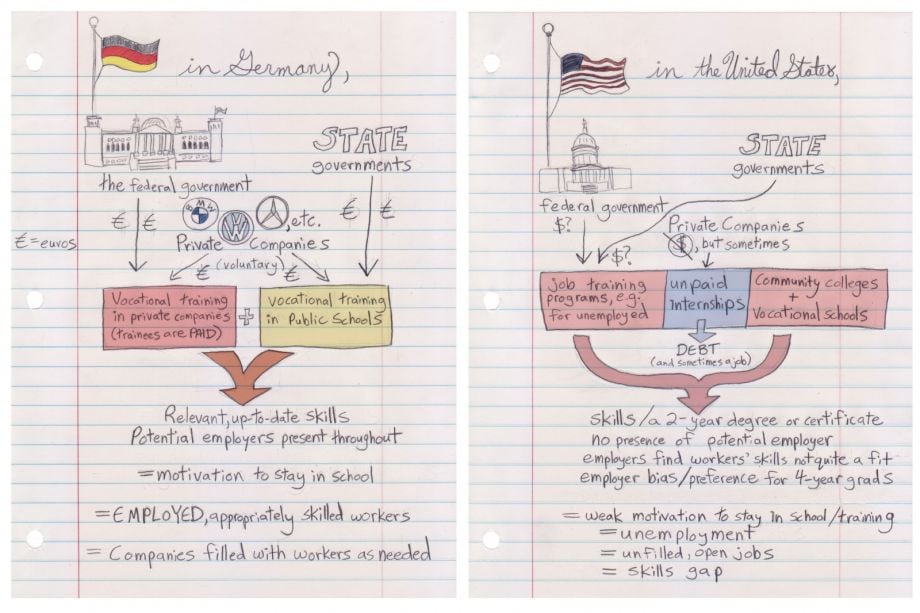

Germany’s vocational education model has its roots in the apprenticeships of the Middle Ages. The system, modulated by national law, marries private companies and public schools. More than a policy initiative cued by an economic downturn or acceleration, Germany’s model has strong scaffolding: The federal government, working through a mandatory chamber of commerce, is responsible for vocational training in private companies, while states are responsible for the same in schools. This dual track system sets up the partnership that leads workers into about 350 formally recognized “occupational standards.” It is viable enough that more than 50 percent of students at college-prep high schools who do not go on to university choose to attend vocational school.

German companies are not compelled by law to participate in workforce training, and they are not typically compensated for their investment of time and talent. If they do participate, they are responsible for two-thirds of the substantial annual costs — about 15,300 euros per trainee each year. Given this, the voluntary participation of employers illustrates the stake they see in developing their workforce as a serious step toward recruitment, skill building and talent retention for their staff. Of course, the involvement of private companies is also a boon to those participating in the training programs. Job seekers are assured that the skills they develop have relevance in the coming economy, and they are motivated to keep up with the training program by the presence of potential employers.

The model is a striking contrast to the current approximation of an apprenticeship system in the United States: The unregulated and specious culture of unpaid internships, positions often held by college students while collecting jaw-dropping debt in student loans. If students receive credit hours in exchange for their internship work, they are effectively paying for the privilege of working for free.

Promoting the vocational model in a recession-weary U.S. begins at the highest level: Edvance is a collaborative program from Germany designed to promote its vocational education and training model with the wider world. Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research partnered with the U.S. Department of Education to deepen its cooperation and collective focus on “green occupations” and “qualifications standards in automotive production.” In 2003, Germany’s Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training signed a cooperation agreement with the American Association of Community Colleges that has led to influential joint conferences and research visits between the two nations.

The non-profit and nonpartisan GMF hosts trips to Germany — like the one Katz took — that provide Americans from a variety of sectors with the chance to witness up close how the vocational system works. The trip is part of GMF’s three-year Cities in Transition Initiative, which looks at how to adapt European models for urban transformation to a U.S. context.

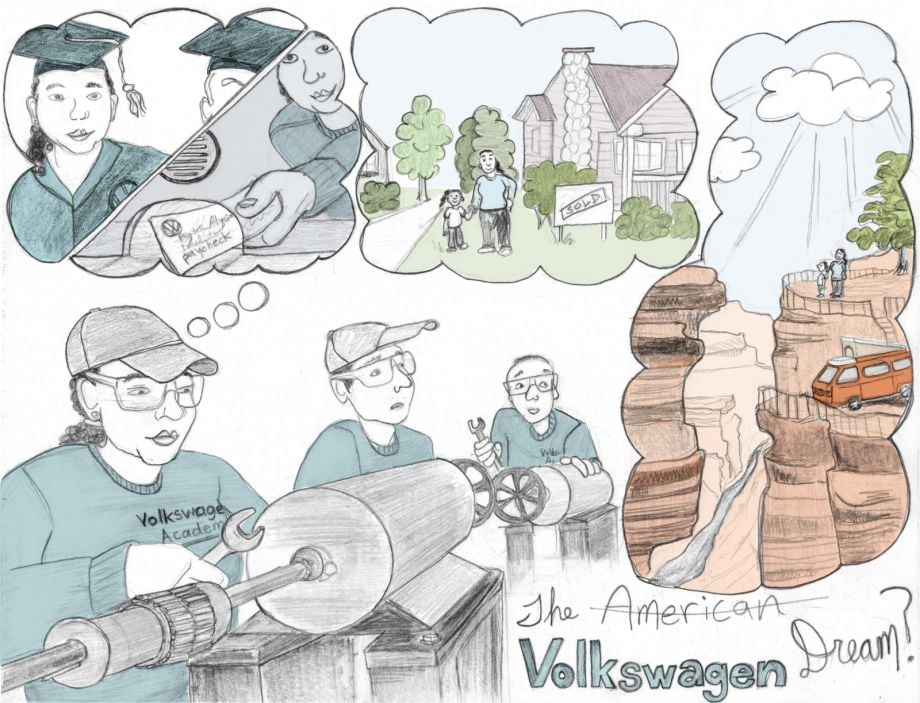

And in Chattanooga, Tenn., where Volkswagen opened a plant in 2010, the German carmaker launched a three-year workforce training program called Volkswagen Academy, developed with Chattanooga State Community College, to meet its need for skilled machinists. About 20 people are accepted in the competitive program each year. After studying and working for up to $13 an hour, they are guaranteed a position at Volkswagen.

As education reporter Dana Goldstein has pointed out, a leading cause behind young people dropping out of high school is the idea that they are not learning anything that will help them get a job. At the same time, unemployment among those without a college degree is far higher than those with one — and only about one-third of Americans under age 30 have a bachelor’s degree. Contrast that with what’s unfolding in Germany, where non-college students often have an occupational certificate by age 20, a qualification that isn’t just a “certificate of participation” but moves them toward real jobs and real wages.

The reason this works in Germany is in large part because of the participation of private companies. Connecting the needs of employers with what workforce development programs, community colleges and economic agencies are actually teaching is the “why” behind the Workforce Intelligence Network.

When WIN formed two years ago, Katz said, “those institutions were struggling to understand where job growth [in Michigan] is. Nobody seemed to know where the economy was going, besides downward. There was a need for better information to understand where growth was actually occurring.” And there was actually growth: More than 300,000 job postings went up in Michigan last year, most of them requiring some high-tech skills.

WIN, then, honed its research to develop four occupation clusters where, it found, jobs in Michigan are increasingly available: Health care, information technology, advanced manufacturing, and retail and hospitality. WIN then put together a group of employers associated with each cluster to develop training and talent retention programs tailored to their needs. Some programs were conducted in-house, and others with WIN’s partner community colleges or employment agencies.

“There are a lot of pilot programs,” Katz said. But it has an impressive roster. The IT cluster includes more than 30 employers among varied industries, including Compuware, Quicken Loans, Kelly Services and Chrysler. Its health care network includes eight major systems, among them the Henry Ford Health System, Beaumont Health System, the University of Michigan Health System and the Detroit Medical Center. The health care network is focusing on the accelerated need for medical billers and coders as the Affordable Care Act takes effect across southeast Michigan. WIN is also do some work with companies in the skilled trades, including Quality Metalcraft. It has just gotten started in the retail and hospitality sector, focusing on career advancement low-skill and low-income workers in Detroit. Each occupation cluster has the full-time attention of one of WIN’s own employees.

A leading cause behind young people dropping out of high school is the idea that they are not learning anything that will help them get a job.

Katz traveled to Germany last November with a group of about 20 economic development professionals. She was impressed with how in Germany, the vocational model doesn’t steer toward a handful of careers, but is — with government support — applied to nearly every occupation. She was partial to a retail and hospitality apprenticeship program, where workers can start at entry level and work their way up to managerial and other top positions. “We [in the U.S.] apply vocational training to five or six jobs,” she said. “If we were more insightful and forward thinking, we would apply it to information technology and other growing careers, and solve a lot of the skills gap.”

But such training relies on employer participation to be effective. While WIN is agitating, and progressing, on that front in southeast Michigan, Katz has found it to be a challenge. A lot of biases on the part of employers stifle their enthusiasm for having a real stake in the quality of the programs, or investing enough to guarantee jobs for successful participants — even when those jobs will otherwise go unfilled.

With Baby Boomers retiring, many employers have a preference for young people, Katz said, putting middle-aged participants at a disadvantage. Also, “there is a significant preference for people with four-year degrees,” Katz said. There’s also a lack of faith in the competency of those who don’t have them.

WIN, which provides information and resources to the agencies that do the actual workforce training, is finding that it needs to adjust its mechanisms to work with potential employers. Despite screenings and successful program completion, Katz said, “we’ve seen some failures. People are getting trained and still [are] not the right fit for employers.” Both screening and actual training need to focus not just on technical skills, but also soft skills. “We give technical skills,” Katz said, “but if [trainees] don’t know how to talk about those skills in an interview, they’re not going to get hired.”

While Katz is focusing on southeast Michigan, Amy Cell is looking at the whole state. Cell, of the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, participated in another GMF-sponsored trip to Germany for workforce advocates in the United States. Cell works closely with the State of Michigan to propel and attract skilled workers. Most striking to her during her time in Germany? “I loved the involvement and commitment employers had in Germany,” she said. “We want to bring that here.”

Cell has found that “the number-one factor for success [in workforce training] is employer engagement… The more companies involved, the better.” But like Katz, she has often found employers reluctant to participate. “If they’re not going to show up to interview people,” she said, “will they hire them in the end?”

Employers believe workforce agencies, Cell said, will “work with certain kind of people they don’t want,” like the long-term unemployed and the formerly incarcerated. Of course, many agencies do work with these individuals — they are among the most in need of support in connecting their skills with available jobs.

Cell has been a major force behind a pilot launching this year, modeled on Germany’s dual track system. Michigan Advanced Technician Training, or MAT2, does indeed engage employers, who actually hire participants at the beginning of a rigorous three-year training program.

The seeds for MAT2 were planted when Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican who once led an economic development organization in Ann Arbor, traveled to Germany in March 2012 and was inspired by the vocational system there. That June, state government staffers that had traveled to Germany met with a number of Michigan employers, many of whom had German parent companies, in Lansing. The group collectively decided to try out Germany’s system at home. After a feasibility study that ended in September, Cell said, all systems were go.

In its pilot stage, MAT2 is partnering with two community colleges in southeast Michigan: Henry Ford Community College in Dearborn, and Oakland Community College in Oakland County. Both have rich roots in the region, and host industry-approved facilities and equipment for specialized training in mechatronics — that is, a hybrid of electrical, mechanical and electronic tools used to solve systems-based problems. Technicians trained in the field support engineers, adjust machines and maintain equipment in high-tech advanced manufacturing companies.

Participants in MAT2 will rotate between shifts in class and shifts on the job, each lasting between nine and fourteen weeks. They’ll get paid an hourly rate while working and also receive a stipend of up to $20,000 for the education, effectively making the program no-cost. MAT2 does not mandate a minimum of employee benefits for the working students, however. After three years, successful participants will have an associate’s degree, as well as a credential certificate recognized in Germany. (Notably, a member of the German American Chamber of Commerce is on the MAT2 advisory board.) Students will be obliged to work for their employer for a minimum of two years, or they will need to pay back their stipend.

The program is targeting about 20 participants in the first year. Each employer will interview them and select between one and five to go to work. Students are also accepted on the basis of their application, including an essay, grade point average and the ACT Compass test.

Already, Cell said, MAT2 is planning to expand the program into additional lines of work, including industrial design and computer programming, and bringing on a larger variety of students. As it stands, there are 11 companies involved, including Brose (which supports the international automotive industry), Detroit Diesel and Kosel, a German company that develops and manufactures advanced electronic, electro-mechanical and mechatronic products. (Michigan, it happens, is home to about 350 German-owned companies.) The MAT2 program is sustained by employer investment, with the partner college assisting. MEDC also is looking to increase its own investment, Cell said, to support the program’s growth across career tracks.

One key element in Germany’s model that Katz doesn’t want to bring to Michigan? In the United States, she said, “what we have here is lifelong learning and ability to move from one career to next. Whereas there, you don’t really have chance to reinvent yourself.” In Germany, the dual system separates teenagers after the 10th grade into programs that are on vocational, academic or mixed track. Once you’re too far along on one track, you don’t really have the option to switch to another.

Katz is resistant to the idea, popular in many school reform circles, that the U.S. should aim to get every student into a four-year liberal arts college. She was the only one in her family who attended college, and several of her siblings did not finish high school. “The structure of college not for everybody,” she said. “A college degree doesn’t necessarily mean you know anything or can do anything. Even college-educated people benefit from having a practical skill.”

At the same time, she said, “we can’t afford to have college track and not-college track,” with no options for those who change their minds down the road and want to cross from one to the other. And she wants to see vocational education as real education, not an opt-out. She pointed out that participants in vocational training programs are able to see, literally, how higher education is applied in the real world, and they are more likely than traditional college students to persist in education.

“In the math classrooms, teachers can talk about why it’s relevant,” Katz said. “People in vocational program see why it’s effective.” She remembered her nephew, a career and technical education student, calling her excitedly when he learned how to make angle platforms using mathematic measurements and other skills. His learning has real-world application. Unlike a lot of his college counterparts, he will graduate debt-free.

“The philosophy in Germany on tracking students doesn’t mesh with the philosophy in the United States and Michigan,” Cell said. “We weren’t going to touch high school.” There is enough upheaval going on as Michigan as it adapts to the new Common Core curriculum and other changes. But she’s all in when it comes to both supporting and creating training programs that draw from some of the most substantial models spearheaded in Germany.

“A college degree doesn’t necessarily mean you know anything or can do anything. Even college-educated people benefit from having a practical skill.”

Of course, when it comes to meeting Michigan’s skills gap and addressing severe underemployment, there’s more to be done than to riff off the dual system. Cell wants to address the outdated myth that manufacturing is dirty, singularly automotive and not high-tech, when in fact much of today’s manufacturing — in Michigan and beyond — is in robotics, biotech and life science engineering. “There is more quantity and variety of opportunities than people realize,” she said, with middle-skill jobs being “huge.”

There are also plain old system-wide inefficiencies to address. The state’s online job search system was relying too much on keyword searching when Cell arrived on the scene. “Most people relate to certain skill type: I’m a welder, I’m a nurse,” she said. But searching for these things didn’t always pick up on appropriate job openings. Someone trained as an accountant might not want to be a CPA going forward. And “nowadays, people are getting very creative with job titles,” Cell said. “If someone looking for a human resources person titles the posting as a ‘payroll guru,’ the right applicant might miss it.”

With new improvements, the online system now tracks up to 10 skill sets that applicants want to use in their potential job. Other improvements made it possible for 1,600 people working at Michigan Works! to run reports on jobs in their area, and applicants can upload — rather than retype — their resumes.

These simple but effective improvements speak to the crux of the matter: How we articulate who we are and what we can contribute to the world. In Marge Piercy’s celebrated poem, “To Be of Use,” she writes:

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

Can WIN, MAT2 and other programs inspired by Germany’s vocational model make a real impact in Michigan, a state sorely in need of a radical reimagining of job training? As Piercy suggests, the question of work — and the programs meant to prepare people for it — goes two ways. It is both about honoring the human need to be of use in the world, while also building a culture that does not lose track, or truncate, or ignore, the abilities of people who could have made the world a better place. The stakes, for all of us, are high.

Forefront is made possible with the generous support of the Ford Foundation.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in Elle Magazine, the New York Times, Politico, the Columbia Journalism Review, Next City and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book. She has been a Fulbright fellow in Nairobi, Kenya and a Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books in 2018.

Follow Anna .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Marian Runk is a Texas-born, Chicago-based cartoonist, illustrator, printmaker, singer-songwriter and birder. Her work has been published by Cicada Magazine, Lumpen Magazine, Narratively and Oily Comics. You can find her online at marianrunk.tumblr.com.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine