Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

On the third floor of Paul Robeson High School, a weathered pile of bricks in Crown Heights, Brooklyn that’s closing next spring due to failing graduation rates, an IBM consultant named Ann McDermott is lecturing to a 10th-grade class of mostly poor, mostly black, mostly boys about the history of the Web.

“Does anyone here know what Tim Berners-Lee did?” she asks, referring to the British computer scientist who invented it.

“World. Wide. Web,” one student murmurs, seemingly bored by the question’s ease.

McDermott nods and continues. “He created it so scientists could communicate. Now we use it to watch cat videos.” The class cracks up. “Who knows how a webpage works?”

It’s not an academic question. These students are enrolled in P-TECH — New York’s Pathways in Technology Early College High School — a new model vocational school designed in collaboration between New York City Schools, the City University of New York and, most notably, IBM, for whom McDermott sells servers. The city, one of McDermott’s clients, provides the funds, facilities and students. CUNY applies a curriculum borrowed from its Early College Initiative, in which students earn degrees without ever leaving high school. IBM supplies internships, mentors and volunteers such as McDermott, as well as the promise of a well-paying job upon graduation.

Five years after the world’s second-largest publicly traded technology company began urging mayors to build “Smarter Cities” using Big Data (at correspondingly big prices), Big Blue has taken it upon itself to reinvent one of any city’s pivotal institutions: public schools.

IBM’s cognitive dissonance illustrates the philosophical tensions between corporate responsibility and profitability, and between sustainability and creative destruction.

In its only two years of existence, P-TECH has won praise from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and numerous educators, not to mention President Obama, who during February’s State of the Union address declared, “we need to give every American student opportunities like this.”

P-TECH’s first graduating class is still four years away, but early results are promising. Nearly half of its students have earned college credits, more will be enrolled this fall in college courses, and virtually all are passing high school. Compare that to a 71 percent graduation rate citywide, and it’s easy to see why Obama hopes P-TECH can be the model for a Race to the Top-style overhaul of vocational education. “We’ll reward schools that develop new partnerships with colleges and employers,” the president said in February.

Emanuel is counting on it, too. A year earlier, the Chicago mayor announced that his city would open five “Early College STEM Schools” explicitly modeled on P-TECH, in partnership with five technology giants: IBM, Microsoft, Cisco, Verizon Wireless and Motorola Solutions, each with a school of its own. All five Chicago schools opened last September — the same month as a citywide teachers’ strike began, prompted in part by Emanuel’s decision to shutter 49 conventional schools.

Not to be outdone, Cuomo has promised to open 10 such schools across New York State, while the Partnership for New York City has pledged $20 million toward building one in each borough. Idaho, Iowa and other states are eyeing the model as well.

This is all by design. The “P” in P-TECH might as well stand for “prototype.”

Nearly half of P-Tech’s students have earned college credits, more will be enrolled this fall in college courses, and virtually all are passing high school.

“You have to have something others can follow, like a cookbook,” says the school’s principal architect Stanley S. Litow, IBM’s vice president of corporate citizenship and corporate affairs. But a better metaphor may be an algorithm — one of the software instruction sets driving the company’s most profitable offerings.

Not even a $100 billion company can afford to give away its ideas for free, and P-TECH was built to scale. Litow’s brainchild is both a school attended by more than 300 teenagers and a petri dish for IBM’s data-driven approach to smartening up secondary and higher education, which Rupert Murdoch has described as “a $500 billion market in the U.S. alone that is waiting desperately to be transformed.”

Litow calls P-TECH a prime example of IBM’s “sustainable” approach to corporate philanthropy, which in this case refers to the company’s ability to sustain profits. “The typical philanthropy model is spare change,” he says. “When you don’t have any, you don’t give any.” For that reason, it’s imperative that IBM’s own philanthropy give back to the business as well, in this case by doubling as research and development.

Litow’s counterpart in this arena is Katharine Frase, chief technical officer of IBM’s global public-sector practice. Frase has experience turning good-faith efforts into cash cows — her previous job was developing commercial uses for Watson, the company’s Jeopardy!-playing supercomputer. (Full disclosure-cum-humble brag: I defeated Watson multiple times as part of its top-secret training regimen against former champions.)

P-TECH suggests the logical end to IBM’s (and its competitors’) smart city rhetoric: Rather than install systems to make public institutions 5 or 10 or 15 percent more efficient, why not invite them to redesign and administer the institutions themselves to make maximum use of the technology?

It also raises a question that has crippled vocational education in America for nearly a century: How can employers handcuffed by profit margins and earnings-per-share targets can make a meaningful difference in something as long-term and patient as education?

It’s a given that membership in the American middle class now requires a college degree. That’s grim news for the third of high school graduates who never make the jump, and worse for the students who leave after only a few credits or semesters — including 75 percent of community college students — often after incurring considerable debt. Which is why P-TECH’s students will receive their degrees with their high school diplomas, after a rigorous six-year education in the fields known as STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). They’ll start college-level courses in their sophomore year with the goal of attaining an associate’s degree in computers or engineering — and with it, a promise to be first in line for a job at IBM.

But there is no line. IBM posted 559 unfilled local job openings in April, according to the New York City Real Time Jobs Report, which listed 252,000 open jobs across the city that month despite a 7.7 percent unemployment rate. It is this apparent mismatch between supply and demand that led Litow to decide the country is facing a “skills crisis” rather than an employment one.

The U.S. currently has 15 million jobs in such industries as health care and IT requiring two years or more of post-secondary education or training, with another 10 million on the way over the next decade, according to Anthony P. Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “Are we going to have just one path to a college degree?” he asks. “Because the one we’ve been building for 30 years is too steep and too frail.”

That’s where IBM comes in. To ensure P-TECH graduates will have the skills necessary to earn $40,000 per year out of school as technicians or system administrators, Litow and his consultants worked with CUNY educators to reimagine the curriculum. In addition to math and science, students learn critical thinking and teamwork through programming and case studies (imagine you work for Samsung, tasked with inventing an Apple iPhone-killer), give PowerPoint presentations as well as write term papers, and use laptops in every class, regardless of subject.

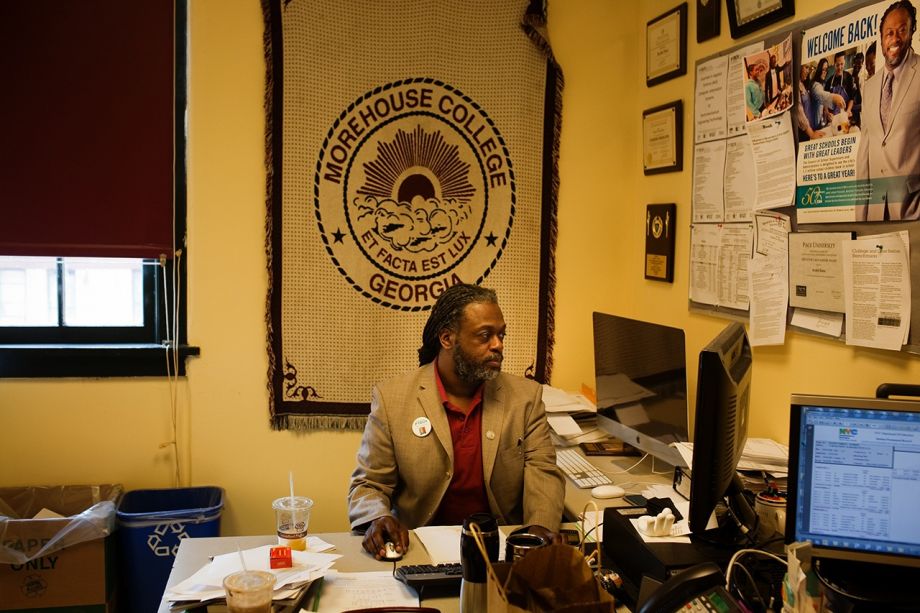

Principal Rashid Davis shrugs at the suggestion the students are only learning how to man a help desk. “Businesses have always been involved in education,” he says on a tour of school. “This is just more of a focus on ensuring students aren’t earning the wrong types of credentials.” With 85 percent of the student population eligible for free or reduced lunches, “we have to be crystal clear about the fact that higher completion rates aren’t happening.”

Also clear is the fact that the logic for P-TECH extends well beyond high school matriculation rates. This fall marks the five-year anniversary of “Smarter Planet,” IBM’s wildly successful rebranding of its analytical software and services, and under that umbrella, “Smarter Cities,” an effort to convince mayors they need Big Data to manage their cities as much as any CEO, if not more. Since then, IBM has worked with hundreds of cities on thousands of engagements, bringing data crunching to bear on crime in Memphis, water in Miami-Dade County and emergencies in Rio de Janeiro, where an “Intelligent Operations Center” has consolidated 30 city agencies under a single roof.

P-Tech principal Rashid Davis shrugs at the suggestion the students are only learning how to man a help desk.

IBM doesn’t break out the financial performance of its Smarter Planet initiatives, preferring to account for them across its various hardware, software and consulting units, although it will say revenue increased more than 25 percent in the first half of this year. Following its corporate trajectory of the last two decades, IBM is “moving away from a company specializing in the supply of technology to a company handling how to apply technology,” according to Michael Dixon, Smarter Cities’ general manager.

But P-TECH may be the first instance where IBM has crossed the line from selling an institution hardware and software to designing the institution itself. This, too, is by design — part of Litow’s insistence on a philanthropic model that’s sustainable by being in sync with corporate strategy. To that end, P-TECH and its descendants are seen within the company as test beds for the next plank in its Smarter Cities effort, which is to build for schools what its operations center is for cities: A single system for collecting, aggregating and analyzing data from students and teachers alike, then writing algorithms to prescribe how to cope with a troubled student just as one might try to reroute a traffic jam.

Davis is certainly correct that American companies have a long history in higher education. Henry Ford opened his eponymous Trade School outside Detroit in 1916 to combat his fear that young boys had lost the ability to think with their hands as well as their heads. The school would go on to produce more than 8,000 machinists during the company’s heyday.

Congress passed the Smith-Hughes National Vocational Education Act a year later, enshrining such vocational schools as separate-but-not-quite-equal, with segregated school boards and curricula. As in Ford’s model, students were trained for particular jobs on the factory floor rather than general-purpose educations. This model would persist through the 1940s and 1950s, when the combination of comprehensive high schools, the GI Bill and Sputnik paranoia prompted the U.S. to double the proportion of college-going high school graduates to an unprecedented 10 percent.

Competitiveness, and fears of America’s lack thereof, was also the guiding principle of the next landmark of education reform, 1983’s “A Nation at Risk” report, which changed the perception of high school to a feeder for college as opposed to an end unto itself. Meanwhile, vocational schooling had come to be seen as un-American, a fundamentally unfair ceiling on expectations more appropriate to collectivist Japan or Germany. “The model became problematic because of the tracking,” Carnevale says. “Vocational training had to go. We basically threw it away.”

We tried to revive it a decade later, when rising economic fears of those same countries — and of American students continually falling behind — led to the School-to-Work Opportunities Act of 1994, which unsuccessfully attempted to blend the two tracks. The political backlash was intense; future Second Lady Lynne Cheney testified before Congress that one mother had asked her, “Who are these people playing God?” (The act quietly expired in 2001.)

Litow calls P-TECH a prime example of IBM’s “sustainable” approach to corporate philanthropy, which in this case refers to the company’s ability to sustain profits.

Stan Litow doesn’t project a God complex, but he is convinced the U.S. needs a paradigm shift on the order of post-war universal secondary schooling. The seed of what would become P-TECH was planted in then-IBM CEO Sam Palmisano’s mind by his friend and New York City schools chancellor Joel Klein, who floated it during a rain delay at one of their annual visits to the U.S. Open. (Klein would later quit to join Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. as the head of its education division, Amplify.) But it fell to Litow, a former deputy chancellor himself, to direct its creation from his cubicle at IBM’s headquarters in Armonk, N.Y. What separates P-TECH from past vocational models, he says, is that “it doesn’t end with IBM hiring these people. That isn’t the end of the battle, it’s the first rung of the ladder.”

Carnevale, who is a fan, argues P-TECH “turns the system on its head — get a technical degree in high school, and then use your higher-wage technical occupation to pay your way through college.” This is both prudent and necessary; in many fields, he adds, an associate’s degree simply isn’t sufficient for long-term attainment, and once students have a taste of college, they want to keep going. “We know three things about these programs,” he says. “[Students] stay in school, they graduate high school and they go for post-secondary education, even when they say that don’t want to.”

Hence IBM’s partnership with CUNY, which not only offers to seamlessly apply credits toward a bachelor’s degree, but also provided the model for P-TECH with its Early College Initiative — 14 New York City high schools offering associate’s degrees from its colleges. (Last year’s graduating class of 744 students across eight schools boasted a graduation rate of 79.6 percent and a college enrollment rate of 77.2 percent.) But whereas CUNY is constrained by the number of schools within its system, P-TECH’s reach is only limited by its ability to find corporate sponsors for each school, which in turn relies on the carrots of good PR and a steady stream of tailor-made entry-level employees.

“Our business is all about scale,” says Litow, who joined IBM 20 years ago following the ousting of his boss, schools chancellor Joseph A. Fernandez. Scalability, of course, is the grail of the education reform movement: How does one take an isolated success, such as a high-performing charter school or the “cradle-to-college” approach of the Harlem Children’s Zone, and scale it both horizontally (across cities) and vertically (within them) to supplement or replace failing schools? And how do you do so without increasing spending or exploiting regulatory loopholes to the point where an apples-to-apples comparison is impossible?

“If the model isn’t constructed to be replicable, all you have is an island of excellence,” Litow says. “It can’t be for 1 percent of students, or require 40 percent more dollars per student, or require a special exam to get in” — all tacit criticisms of various charter schools which claimed to have cracked the code despite their glaring exceptionalism. “The question is whether it’s for 1 or 2 percent of students, or 50 or 60 percent. Or 90 percent.”

Asked whether early college STEM schools could possibly replace 90 percent of American schools, Litow professes to have no idea. But, as a start, he would like to see the roughly $1 billion in federal funds earmarked annually for “career and technical education” repurposed for a national network of schools using the P-TECH playbook as their guide.

Several education scholars I spoke with were hopeful of P-TECH’s prospects and said that it skirted the reform movement’s usual pitfalls, such as “creaming,” i.e. skimming the best incoming students off the top via an entrance exam. (The school has open enrollment.) But they also expressed concern it was scaling too far, too fast in the absence of definitive data. After all, its first class is still four years away from graduating.

“It sounds great, but can it be more than 100 or 200 or 300 students when there’s a thousand students in the same building who might be served by this?” asks Thomas Bailey, director of the National Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment at Columbia University’s Teachers College. “And if you want this to be system-wide, who else,” referring to the corporate partners, “do we want doing this?”

Perhaps, I ask Litow, we should wait for those results before building these schools by the dozens, if not hundreds. He is unmoved. “Innovation should move rapidly,” he says. “If every software company waited until their software tool was perfect before they went from 1.0 to 2.0 to 3.0, you wouldn’t have any innovation… If this model wasn’t working, people shouldn’t embrace and adapt it.” But it is, he argues.

IBM would like to do for education what it’s already done for health care. Just as Smarter Cities is an essential plank in the broader Smarter Planet platform, so is “Smarter Care,” a market the company estimates is worth tens of billions of dollars. That effort, Frase explains, began through a partnership with a health care provider in Troy, N.Y. Austin, Texas involving aggregating and analyzing patient data. IBM worked with Seton Healthcare Family to first predict how patients would respond to treatments, and then prescribe the treatment its Big Data believed was most likely to succeed. Seton Health’s test was to predict which men from a group suffering congestive heart failure would be readmitted within 30 days.

“It had nothing to do with how they felt when they left,” Frase says. “The factors that mattered were social. Does he live alone? Addiction? Something that makes him unlikely to do what a doctor has written down for him?” The answer wasn’t hiding in the patients’ “structured” data — e.g. their cholesterol scores or blood pressure — but in the “unstructured” notes around it. “Using those indicators to intervene in the social context has a huge payoff,” she says.

Is the same true for education? Anti-reformers such as former Assistant Secretary of Education Diane Ravitch have assailed Race to the Top’s high-stakes testing and teacher evaluations as too quantitative for their own good. They assert environmental factors such as poverty and families are as responsible for students’ poor performance, if not more so. (P-TECH’s Davis might agree; he would prefer to run it as a boarding school and subject incoming students to rigorous summer programs “before life gets in the way.”)

Frase isn’t sure. “When I talk to education people, what they’re fascinated by is whether there’s enough data to prove these theories.” Health care, she notes, has more longitudinal data, better standards and better consensus on what constitutes success than education. But P-TECH offers IBM a unique opportunity in that it will retain graduating students’ data for the next cohort, which is essential for creating forecasts. Individual student records are proprietary by law; building your own school is the only way to obtain them.

“The big challenge now is whether we can become prescriptive. Can I not just tell you these kids are at risk, but that they’re best handled this way and not that way?” says Frase, who by way of example tells the story of her son’s fourth-grade teacher, who inherently understood he was a kinesthetic learner who learns by doing rather than listening. He entered her class two grades below reading level; he left ahead of the curve. “We can’t clone her,” Frase says, “but can data do that?”

IBM intends to find out. While its previous work for Wichita State and Hamilton County were one-offs, Frase is overseeing the development of a software “infrastructure layer” for schools, running behind the scenes to manage students’ digital textbooks and analyze their performance.

Rupert Murdoch has described the market for educational software and technology as a “$500 billion market in the U.S. alone that is waiting desperately to be transformed.”

P-TECH, basically, is a research project for gleaning best practices that can be codified into software or peddled by IBM’s consultants to other clients — in this case, schools. Just as it would never dare to treat Seaton Health’s patients, the company has zero interest in teaching children, Frase says. But when asked whether IBM would be willing to build a hospital in its data-driven image, she concedes that it would, and that P-TECH and its successors are very much the same. Like her son, IBM is a kinesthetic learner: “P-TECH is learning by doing.”

For cities, P-TECH is an alluring model because it addresses the challenge of keeping kids in school as well as finding them jobs after graduation. High school dropouts suffer from lower incomes, higher unemployment rates, increased need for medical care (with less ability to pay for it) and higher incarceration rates — all of which is indirectly borne by taxpayers. Education economists Henry M. Levin and Cecilia E. Rouse have suggested that cutting national dropout rates in half would produce a net benefit of $90 billion annually.

Not that a diploma is much help. The unemployment rate for high school graduates is twice as high as unemployment among those with a Bachelor’s degree, according to an April report published by Demos. The job prospects for Millennials are bad in general, and worse for the African-American students who comprise the majority of P-TECH’s student body. Nearly half of the nation’s unemployed are between the ages of 18 and 34, Demos found, and one in four African Americans in the same age group is currently looking for a job but cannot find one.

For universities, dropouts represent lost tuition revenue and the opportunity cost of forgoing a different student. Wichita State turned to IBM six years ago to identify and recruit “high-yield prospects” more likely to enroll, then helped match them to the appropriate courses to boost graduation rates and course registration. Today, administrators and department heads use its software to weigh the costs and benefits of everything from scholarships to evening classes.

Other customers have already begun taking steps toward building the crystal ball Frase has in mind. Hamilton County, Tenn. (which includes Chattanooga) asked IBM to help develop profiles for each student across its 78 schools, along with algorithms to predict potential dropouts and flag them for intervention. In doing so, it boosted graduation rates by eight percentage points — to 80 percent countywide — in a single year.

It’s not first time IBM has married philanthropy with business development. Prior to P-TECH, Litow created its Corporate Service Corps, which dispatches teams of a dozen or so on pro bono missions in emerging markets where IBM has little or no presence. John Tolva, formerly the company’s leading Smarter Cities evangelist and currently Chicago’s CTO, joined one of the first teams sent to Ghana in 2008 to help local businesses — and to introduce them to IBM.

“It’s very long-range market development,” Tolva says today of the program. “You wouldn’t you have known we were IBMers there — we weren’t wearing uniforms, and we certainly weren’t selling anything — but there’s now an office in Accra.”

Two years later, facing a dearth of urbanists within the company, Litow started the Smarter Cities Challenge to donate $50 million worth of consulting services to 100 cities over three years. In the process he created 600 urban experts, not to mention the P-TECH playbook, the product of a 2011 grant to Chicago. “What was missing in the early days was a certain sociological viewpoint,” Tolva says. “That wasn’t IBM’s fault. Cities are the weirdest system to quantify. Now, from what I’ve seen on the outside, they really understand that.”

With the five-year anniversary of its Smarter Planet campaign approaching, IBM has made the prescriptive capabilities Frase talks about the centerpiece of its most recent engagements. Whether it’s water, power, traffic or police, IBM is writing algorithms to reroute or reduce them as necessary. Beyond cities, Watson has recently been re-tasked with reading everything there is to know about genetics, personal finance and media habits to advise doctors, bankers and advertisers on the best course of action, informed by the debatable assertion, as Frase puts it, that “if you could just see it, you would make a better decision.”

Asked whether P-TECH and its successors represent the logical next step from advising civic institutions such as schools to designing and running them — to do for cities what Booz Allen Hamilton does for the intelligence community — Michael Dixon draws a bright line between them. “IBM is not a bank, it’s not a telco and it’s not a government,” he says. “We work to support banks and telcos and governments, but they are not our business. You have to make a distinction between operations and policy.”

P-Tech students start college-level courses in their sophomore year with the goal of attaining an associate’s degree in computers or engineering.

Sometimes, however, IBM will walk right up to that line and peer over it. The biggest obstacles to creating smarter cities, Dixon says, “are not economic, political or technological. They’re organizational, historical and cultural.” It is not lost on civic leaders that making the most of IBM’s offerings often require wrenching organizational change. “And we’ll say, ‘Yes, it does,’” Dixon says. “But it’s not our job to change the government, and we stop well short of doing so.”

Or at least it tries not to. But a smarter city (or school) isn’t simply one that’s 15 percent more efficient than its dumber neighbors. If a municipal government’s culture can inhibit how it uses technology, then the reverse is also true: The use of technology can rewire the circuits of power. IBM has seen this firsthand in Rio de Janeiro, where it assisted Mayor Eduardo Paes in building the Intelligent Operations Center, which began as a disaster management center but quickly became the means to manage 30 city agencies from a single perch. “I encounter lots of different kinds of cities,” said Frase’s predecessor, Guru Banavar, in 2012. “I can’t say I’ve seen any other city that has this level of coordinated governance.” Data-driven decision-making inevitably changes how decisions are made in cities, and who makes them.

Similar transformations have occurred at universities. David Wright, Wichita State’s associate vice president for academic data systems and strategic planning, describes a culture in which only those sufficiently armed with data have a voice in meetings — which typically doesn’t include the faculty. “They don’t see the big picture that we have to have revenue,” Wright says, “that we need to be able to see it coming in and project it into the future.”

From its very beginnings, IBM has played a hand in the evolution of several of our most cherished institutions. The company’s oldest roots lie in the creation of special tabulating machines for the 1890 Census, which were commissioned after the previous census had taken seven years to finish. In 1937, it began shipping the IBM Type 77 collators, designed at the behest of the Social Security Board to automatically add payroll contributions to social security accounts — a task which might otherwise have been impossible. And following the Second World War, IBM legitimized “computer science” as an academic discipline, in no small part to guarantee a skilled workforce that could keep pace with its expansion.

Which brings us full circle to P-TECH, which derives no small part of its own legitimacy from the fact that graduates presumably have a job opening waiting for them at IBM. Or so they hope.

What if IBM had proposed P-TECH 20 years ago, during the last public groundswell of support for vocational education? Very little at the company was sustainable then. Long in decline, Big Blue bottomed out in 1993 with an $8.1 billion operating loss and a new CEO, Lou Gerstner, who put the company on its current course and subsequently pulled off one of the greatest turnarounds in U.S. business history. Today’s IBM is seen as a paragon of success. One of America’s most admired companies, its free cash flow has nearly tripled since 2000 to $18.7 billion after shedding its PC business in 2004 to focus on software and services.

Capitalizing on its success, IBM is pursuing an ambitious plan to boost earnings per share to $20 by 2015, which will require aggressively increasing revenue, earning half its profits from software (rather than services), chasing new business in growth markets overseas, and “generat[ing] $8 billion in productivity through enterprise transformation,” according to last year’s annual report. In English, this means trading in expensive people in developed countries for less expensive ones in the aforementioned growth markets. Last month, following two consecutive quarters in which revenues and profits fell, the company announced a $1 billion charge for “workforce rebalancing” this year, a lump sum which masks who Big Blue is hiring and firing, and where.

Excluding top management, IBM’s U.S. headcount has steadily decreased from 133,789 in 2005 to an estimated 91,000 last year — a decline of 32 percent, according to the Alliance@IBM, an employee organization agitating for union recognition. (IBM doesn’t publish headcount figures by geography.)

On June 12, the company notified more than 3,300 U.S. and Canadian employees they had been terminated. The majority of the affected positions — which are listed in granular detail on the Alliance@IBM website — “are skilled tech jobs, the kind the students are striving for,” says Lee Conrad, national coordinator for the group. Those are the jobs IBM increasingly hires for overseas. In 2009, the last year geographic data is available, IBM hired 18,873 workers in India, another 13,376 in the “Asia/Pacific” region, and just 3,514 in the U.S., which is now home to less than a quarter of IBM’s total workforce — and less than India’s, which today has 112,000 employees. An IBM spokesperson declined to comment on these numbers.

IBM’s cognitive dissonance illustrates the philosophical tensions between corporate responsibility and profitability, and between sustainability and creative destruction. It also underscores the inherent limits of any educational model which depends on close corporate partnerships to either guide curricula or promise the first crack at a well-paying job at the end of six years — because no one can guarantee IBM will still need their skills when P-TECH’s first class graduates in 2017. The company nearly sold a multibillion-dollar chunk of its server business this spring to Lenovo, for example, before talks broke down over price. Palmisano has credited the ruthless divestiture of its PC division and other hardware units as pivotal to the firm’s continued success. IBM’s resolve to shed low-margin commodities in favor of high-skill, high-margin ones — such as Smarter Planet — would seem to be at odds with its promise to hire systems administrators with associate’s degrees (or to at least consider it).

Excluding top management, IBM’s U.S. headcount has steadily decreased from 133,789 in 2005 to an estimated 91,000 last year.

To be fair, no one at IBM sees P-TECH or its descendants as a recruiting pipeline. Frase characterizes them as feeders for the broader “ecosystem” of partners, suppliers and other technology companies it might do business with in the future. But the long-term health of that ecosystem is by no means guaranteed, either.

For example, the partners of Chicago’s schools include Microsoft — which recently announced a sweeping reorganization as it grapples with the slow death of the PC — and Motorola Solutions, the rump of a once-great local company that only two years ago dismembered itself before selling its cell phone half to Google. Another partner, Cisco, is currently unable to offer graduates the same fast-track promised to graduates of P-TECH. “They asked us, and our attorneys are working on it,” says Jerry Rocco, the company’s account manager for the city of Chicago. “We don’t hire high school graduates hardly at all.” (Last week, Cisco announced it would cut 4,000 jobs, or 5 percent of its workforce, only two years after firing another 6,500 employees, which at the time represented 9 percent of the total.)

Long before P-TECH was a gleam in Joel Klein’s and Sam Palmisano’s eyes, the U.S. had a robust apprenticeship system designed to teach factory workers skills on the line. It disappeared, Carnevale says, because a manufacturing sector which once employed 30 percent of Americans today employs less than 10. “In the end,” he says, “American employers are not going to take on this function en masse.” Despite flashes of interest at times when labor markets tighten up, the attention deficit disorder that comes with being a public company beholden to earnings targets means private employers will inevitably lose interest when conditions change. “IBM is great, but how many IBMs have we got?”

Don’t expect a nationwide chain of IBM-backed STEM academies anytime soon. Besides P-TECH and its Chicago sibling, IBM is likely to sponsor two of Cuomo’s proposed schools at most, according to Litow, who declines to name an upper limit on how many the company is prepared to unilaterally support. IBM’s interest in public education will last for as long as profits are able to sustain it. Helping matters along is the fact that educational software alone is currently a $2.2 billion market, which Bill Gates believes could grow four-fold in the near future.

But as competition to build smarter cities mounts — last month, Microsoft made its long-belated entry into the market with CityNext — IBM will face the same relentless pressure as it does in its other markets, racing to “remix to higher value” ahead of its competitors by eschewing selling technology in favor of selling how to use it. As cities, schools and everyday life become increasingly data-driven, P-TECH suggests these companies will not only sell the smarts, but also the cities themselves. Because there are limits to what technology can do, even in the classroom.

Forefront is made possible with the generous support of the Ford Foundation.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Greg Lindsay is a contributing writer for Fast Company and co-author (with John D. Kasarda) of the international bestseller Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next.

His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, The Financial Times, McKinsey Quarterly, World Policy Journal, Time, Wired, New York, Travel + Leisure, Condé Nast Traveler and Departures. He was previously a contributing writer for Fortune and an editor-at-large for Advertising Age. Greg is a two-time Jeopardy! champion (and the only human to go undefeated against IBM’s Watson).

Alan Chin was born and raised in New York City’s Chinatown. Since 1996, he has worked in China, the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq and Central Asia. Domestically, Alan has followed the historic trail of the Civil Rights movement, documented the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and covered the 2008 presidential campaign. He is a contributing photographer to Newsweek, the New York Times and BagNews, an editor and photographer at Newsmotion and a photographer at Facing Change: Documenting America (FCDA). Alan’s work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine