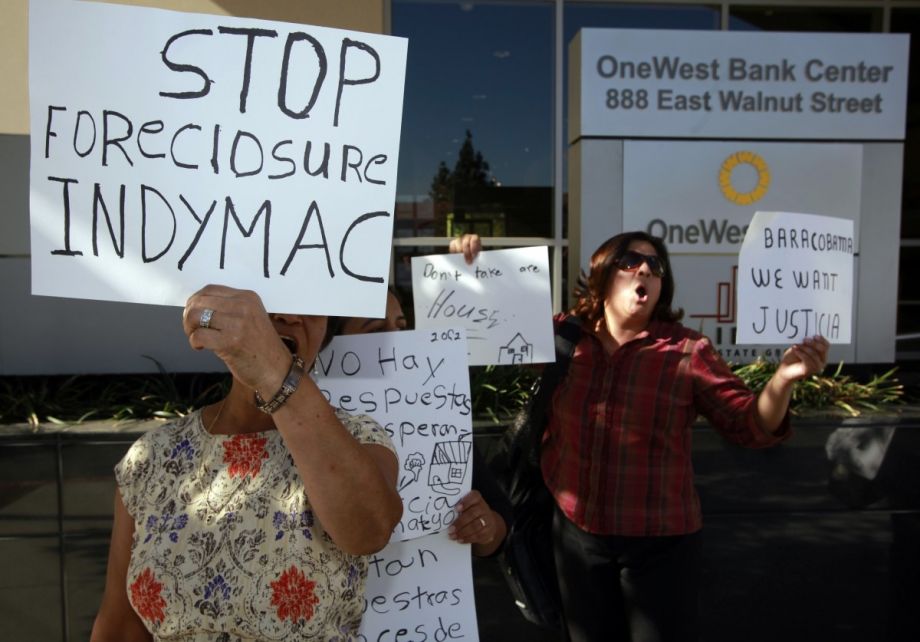

Two California nonprofits Wednesday filed a complaint requesting that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) investigate OneWest Bank for redlining and violations of the Fair Housing Act. Steven Mnuchin, who has been Donald Trump’s national campaign finance chairperson since May, and who is now reportedly the leading pick for treasury secretary in the new administration, held a top job at the bank as recently as last year.

In 2009, Mnuchin, a Wall Street veteran and movie producer, led a group of investors to purchase the remains of the failed IndyMac Bank from federal regulators. IndyMac had been one of the big subprime mortgage lenders whose string of failures culminated in the financial crisis and resulting Great Recession. The investor group renamed the resurrected bank OneWest, and Mnuchin became chairperson.

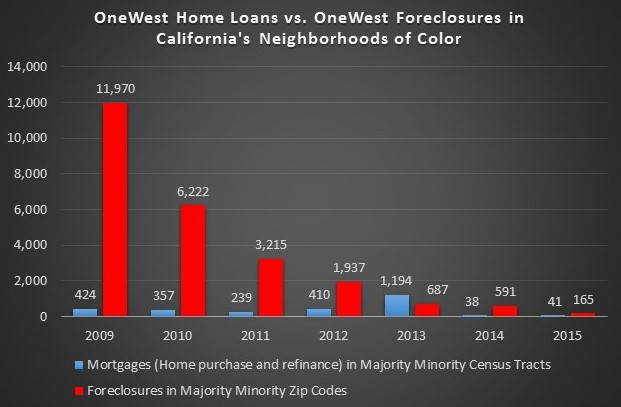

As with many subprime lenders, IndyMac had made mortgages without asking borrowers anything about their income, and many of those loans went to people of color, in working-class or poor neighborhoods. Under the new OneWest banner, the bank began to foreclose on many of those borrowers. Meanwhile, according to home mortgage data from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, OneWest just about stopped making any new loans to people of color. During Mnuchin’s chairpersonship, from 2009 to 2015, OneWest made 269 home purchase or improvement loans in California — only 16 went to Latino borrowers, and only two went to African-American borrowers.

(Credit: CRC)

Filing this Fair Housing Act complaint on the heels of the Nov. 8 presidential election is only a coincidence, according to Kevin Stein, deputy director at the California Reinvestment Coalition (CRC), one of the two nonprofits involved.

“We had been engaged with the bank for a few years and had been a strong protester of their proposed bank merger,” Stein says, referring to the sale of the bank last year to CIT Group, an NYC-based commercial financing company.

Under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), federal bank regulators have the authority to deny a merger in cases where a bank has failed to meet its obligations to meet the credit needs of all those in the communities where it does business. As it usually does for any bank merger or acquisition in California, CRC led efforts before the merger last year to gather and present data and comments to regulators about alleged discrimination in OneWest’s bank branch locations and lending.

Out of the six California counties where OneWest does business, including Los Angeles County, CRC found that 11 of its 74 branches were in a majority Latino census tract, one was in a majority Asian tract, and none were in a majority African-American census tract. In Los Angeles County, where 61.5 percent of the population is nonwhite, 82 percent of OneWest’s home mortgages went to white households in 2015, CRC found.

Regulators received over 2,300 comment letters both in support of and in opposition to the merger. Around 1,700 of the letters resulted from an email campaign initiated by CIT Group and OneWest Bank seeking support for the merger. Regulators also received two petitions in opposition, with over 21,500 signatures.

Given the level of opposition to the merger, regulators ordered OneWest Bank to come up with a CRA plan, in consultation with CRC and other grassroots groups in California. That resulted in a four-year, $4.6 billion CRA plan. Federal regulators finally approved the merger in July 2015.

“We have dealt with a lot of financial institutions and we have seen a lot of mergers, and this was certainly one of the most problematic mergers and institutions that we have been involved with,” Stein says.

CRC felt the plan did not go far enough. While OneWest’s CRA plan promises to expand the bank’s presence in minority communities and lending to minority borrowers, it did not include any provision to make restitution for its 36,000 foreclosures since 2009. CRC found that 68 percent of OneWest foreclosures happened in majority-minority ZIP codes.With the merger review avenue exhausted, CRC joined forces with Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California (FHANC, formerly Fair Housing Marin), a CRC member, which had separately been investigating OneWest Bank since April 2014, gathering information on possible violations of the Fair Housing Act. Their joint filing is CRC’s first ever complaint filed under the Fair Housing Act. “That says something in itself,” Stein adds.

As one of many local chapters nationwide of the National Fair Housing Alliance, FHANC supports 10 to 15 individuals a year to file complaints about discrimination in the housing market. A typical example is when a potential homebuyer who is black finds a newly posted listing, and visits the property only to be told by a white homeowner or broker that the property is no longer available. When such a case comes to FHANC, they send test buyers of different races to view the property to determine if the homebuyers are given different responses based on race.

FHANC also files one or two complaints a year as an agency, but it is usually in coordination with sister chapters in other states that are filing their own complaints against a large national mortgage lender. OneWest was a rare case of a single-state complaint, this one focused on disparate treatment of bank-owned properties.

“We began investigating the way in which banks manage foreclosed properties around 2013 or so,” says Caroline Peattie, executive director at FHANC.

After a foreclosure, when properties fall into bank ownership, the bank has a theoretical incentive to find a qualified buyer and give them a mortgage for the home as soon as possible, so it can earn revenue instead of paying property taxes. There’s also theoretically an incentive to keep the property in optimal condition, make repairs if needed, and to market the property widely, in order to fetch the bank the highest possible price. Good for the bank, good for the new homeowner, good for the neighborhood.

What FHANC says it found, using its own in-house investigative staff, was a pattern of OneWest Bank maintaining and marketing properties in majority-white neighborhoods, while neglecting maintenance and marketing of properties in majority-minority neighborhoods.

FHANC investigated 16 OneWest-owned properties, 13 in majority-minority neighborhoods and three in majority-white neighborhoods. They sent investigators out with checklists covering 39 different items, and took photos of properties inspected.

Eight of the OneWest-owned properties in majority-minority neighborhoods had substantial amounts of trash on the premises, while none of the REO properties in majority-white communities had the same problem. Eight properties in majority-minority neighborhoods had overgrown grass or dead leaves, while none in majority-white communities had the same problem. Eight properties in majority-minority neighborhoods had no professional “For Sale” sign posted, while all the properties in majority-white communities had one. Properties in majority-minority neighborhoods also had damaged siding, missing or out-of-place gutters, or exposed and tampered-with utility connections, none of which was found on properties in white neighborhoods. The list goes on and on.

“Investigating these properties takes way longer than you can imagine,” says Peattie.

The cumulative effect starts with depressing the value of that one property as well as those surrounding it, but it goes way beyond that, Peattie says.

“From our perspective, the cost to neighborhoods of color is much higher and more insidious than real estate values. There’s a very high price to pay in terms of health and crime,” Peattie explains. “Neighborhoods with poorly maintained homes are more likely to experience physical and mental health problems.”

The health dangers are short- and long-term. At one of the OneWest properties, there was a pool that was full of green, brackish water. “If our investigators can walk back there, so can kids,” says Peattie.

Despite the fact that FHANC brought up some of these findings during the earlier CRA plan negotiations with OneWest, the plan makes no reference to the disparate treatment of bank-owned properties based on racial demographics of neighborhoods.

Wednesday’s Fair Housing complaint requests that HUD investigate OneWest Bank’s lack of branches in minority neighborhoods, lack of lending to minorities, and its disparate treatment of bank-owned homes based on racial demographics of neighborhoods.

If he were to become treasury secretary, Mnuchin would not be directly involved with investigating the complaint and levying any settlement payments or other penalties. That would fall on the future HUD secretary’s plate. But if Mnuchin’s own record on existing banking and housing regulations is any indication of the administration’s approach to the CRA and Fair Housing Act, things could turn out bleak under a new administration.

It’s happened before. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration passed the 1968 Fair Housing Act, one of its final and most important achievements, but under successor Richard Nixon, FHA was basically rendered toothless for the first generation of bureaucrats charged with implementing the law.

“Certainly after this election the American people want to hold big financial institutions accountable for taking advantage of working people, and that is one lens of looking at this institution, which has foreclosed on 36,000 working-class families and seniors,” says Stein. “These are the bedrock principles of access and opportunity and giving people a fair shot.”

“My fingers are crossed that somebody would be appointed [as HUD secretary] who would understand the whole concept of fair housing,” Peattie adds.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)