Anticipating a less affordable future, Philadelphia is considering requiring developers of residential projects of 10 units or more to set aside 10 percent of units at rents or purchase prices below market rate. New Orleans has a similar voluntary program right now — and it could become permanent. In Boston, developers can pay into an affordable housing fund to get zoning clearance to build bigger.

Such programs and policies, referred to as inclusionary housing or inclusionary zoning, are being used across the U.S., but their reach is uneven, according to a new working paper from the think tank Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Grounded Solutions, a national network of inclusive housing organizations. Also uneven: the way cities track what these policies accomplish.

The paper, authored by Emily Thaden and Ruoniu Wang, claims to be the most comprehensive survey to date of inclusionary housing programs, and identifies 889 jurisdictions using the approach and examines data on 791. Many jurisdictions reported having multiple inclusionary housing programs, adding up to 1,379 total in the U.S.

The authors define inclusionary housing as any program or policy that requires or offers incentives for the creation of affordable housing when new development occurs. They called and emailed jurisdictions to request data on everything from how much housing and what type of housing (for rent or for sale) the programs have produced, to what income levels they are serving, and more.

Of the data available — not everyone has been keeping precise records — the inclusionary housing programs that Thaden and Wang surveyed posted a tally of 173,707 units of affordable housing created. (“Due to missing data, these numbers substantially underestimate the total fees and units created by the entire inclusionary housing field,” they note.)

Of the 173,707, 122,320 were rentals (across 581 jurisdictions), and 49,287 were for homeowners in multifamily buildings (across 443 jurisdictions). In addition, 373 jurisdictions reported raising $1.7 billion through developer fees for affordable housing. (Some cities allow developers to pay “in lieu” fees into a pot of money that fuels affordable housing development, and the developer is not required to include below-market-rate units in a new building.)

That said, 80 percent of jurisdictions with inclusionary housing programs are located in just three states: New Jersey, California and Massachusetts. It’s due largely to state laws or judicial decisions, the paper notes.

Since 1969, California’s Housing Element Law has required that all local governments, including cities and counties, plan to meet the housing needs of everyone in the community. Since 1979, California’s Density Bonus Law has required local governments to provide density bonuses and other incentives to developers of affordable housing or housing for other specified vulnerable groups like seniors or youth aging out of foster care.

Meanwhile in Massachusetts, Chapter 40B was enacted in 1969 to address exclusionary zoning statewide that prevented the development of low- and moderate-income housing subsidized under federal or state programs. The goal of this state statute is to make at least 10 percent of housing stock in each community affordable for moderate-income households. The state has since created programs and additional measures to create accountability and support progress toward that goal, with limited effect. As of 2014, 48 out of 351 communities had met this goal, according to Thaden and Wang.

In New Jersey, two landmark state supreme court decisions involving Mount Laurel Township declared municipal land use regulations that prevent affordable housing for low-income individuals and families are unconstitutional, and mandated that municipalities take affirmative action to provide the locality’s fair share of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income households.

The first inclusionary housing program, as defined by Thaden and Wang, was enacted by Fairfax County, Virginia, in 1971. Adoption of inclusionary housing has accelerated since then, with 115 since 2000 including 72 from 2010 to 2016 alone.

The most popular incentive given under inclusionary housing programs has been a density bonus, allowing developers to build more units onsite than current zoning allows, in exchange for onsite affordable units or developer fees.

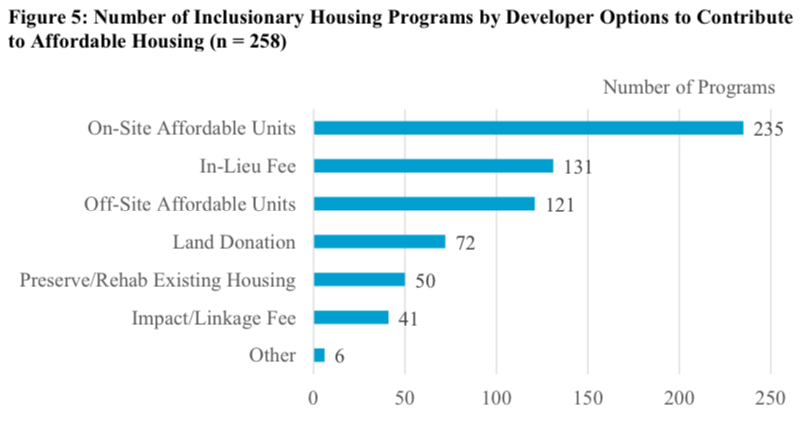

Inclusionary housing programs also typically give a range of options for developers to contribute to affordable housing either onsite or off-site through other construction or fees. Some cities may negotiate for some of the developer’s obligation to be satisfied onsite and some satisfied offsite. Thaden and Wang also surveyed programs for this information.

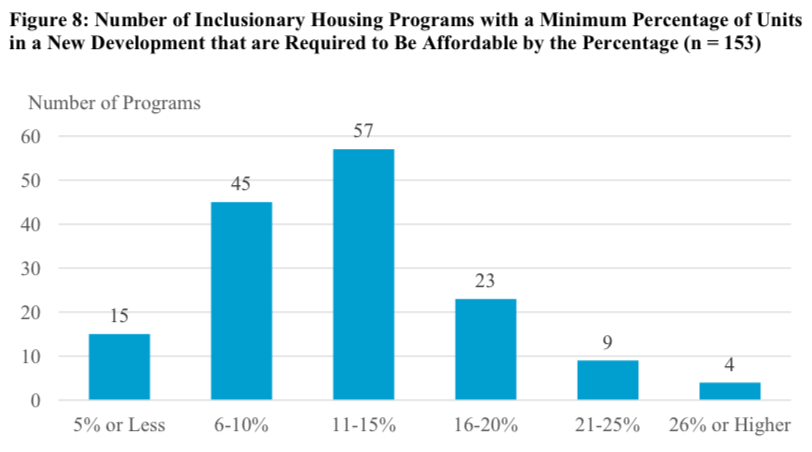

For instances where inclusionary housing programs required onsite affordable housing, Thaden and Wang surveyed what percentage of units (or in some cases square footage) was set aside for affordable housing.

Issues around developer fees instead of onsite affordable housing units are worth further study, Thaden and Wang write. Proponents of developer fees often argue that collecting fees can generate a higher volume of affordable housing than requiring some small percentage to be located in new construction. But one of the original goals of inclusionary housing policies was to reduce concentrated poverty and create more equitable access to high-performing public schools, parks and other public amenities. According to Thaden and Wang, minimizing fee options may be an effective shift to promote affordable housing in asset-rich areas. They also note that there’s been a shift away from the developer fee model since 2006.

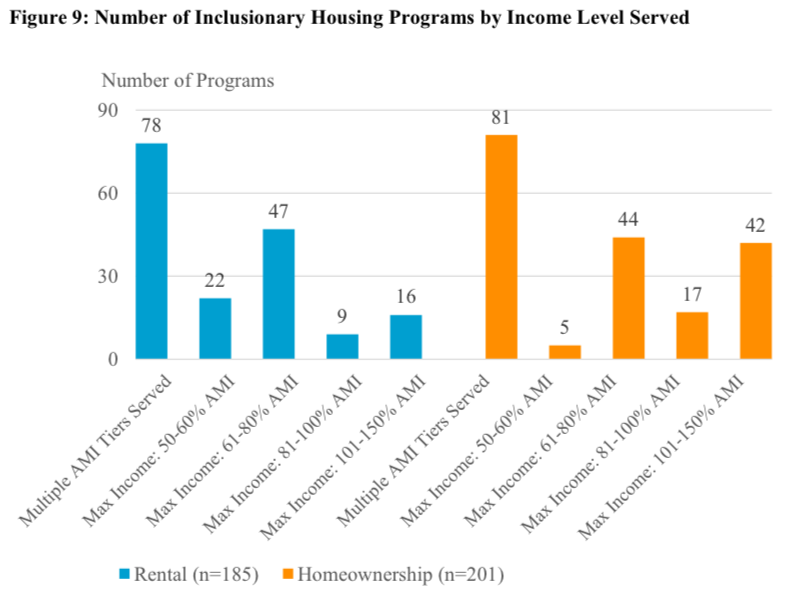

Digging even deeper than mere production, Thaden and Wang surveyed programs for information on who has benefited from inclusionary housing programs. It’s a growing point of contention in cities where affordable housing production does not quite match up with the affordable housing needs of the market.

New York City, for example, is in year four of a 10-year plan to spend upward of $40 billion and use inclusionary zoning to build and preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing. Yet according to one study, most of the units being built are not affordable for most of the city’s rent-burdened population — leading many residents and activists to ask repeatedly, “Affordable for whom?”

Looking at 185 inclusionary housing programs that provided the necessary data, Thaden and Wang found that most programs are serving multiple income tiers, with the most common tiers served being those between 50 and 80 percent area median income.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)