Philadelphia City Council President Darrell Clarke unveiled a new plan this week to address what he calls a housing affordability “crisis.”

Creatively titled “The 1,500 Affordable Housing Units Initiative,” the proposal calls for the construction of 1,000 affordable rental units and 500 purchasable homes, with the goal of reducing the backlog of 110,000 people on the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s waiting list.

The 500 homes would come from transferring city-owned vacant properties to non-profit and private developers for low fees with a restrictive deed covenant attached, requiring that they be sold to households who earn between 80 to 120 percent of the Area Median Income. Philly’s AMI is officially $78,800 for a family of four, though PlanPhilly’s Jared Brey notes the actual median income in Philadelphia County is $37,016.

The 1,000 rental units would be financed with a $100 million bond issue and some complicated public finance alchemy leveraging an underused 4 percent federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit.

While it’s always good to see well-meaning city leaders engaging with housing affordability and cost of living issues, the big problem with Clarke’s plan is that the housing affordability “crisis” he’s worrying about doesn’t actually exist. The impetus for the plan rests on a misreading of the policy implications of a recent Urban Institute report, cited in Clarke’s press release:

In 2012, for every 100 extremely low-income renter households in Philadelphia there were only 37 available affordable rentals units, according to the nonpartisan Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. In total, there were 43,700 affordable and available rental units for 117,578 extremely low-income renter households in Philadelphia.

Clearly this is a huge problem. But it isn’t really a housing problem — it’s an income problem.

The housing itself is quite cheap here compared to most of Philadelphia’s peer cities. The real issue is the 28.4 percent poverty rate, one of the highest in the nation. Cheap as the housing is in absolute terms, a sizable segment of the population still doesn’t earn enough money to afford it.

Clarke’s own report knows this. It defines affordability, on pages six and 18, as housing that costs 30 percent or lower of Area Median Income. That definition is problematic for reasons I’ll come back to, but by this standard Philadelphia largely achieves Clarke’s goal already.

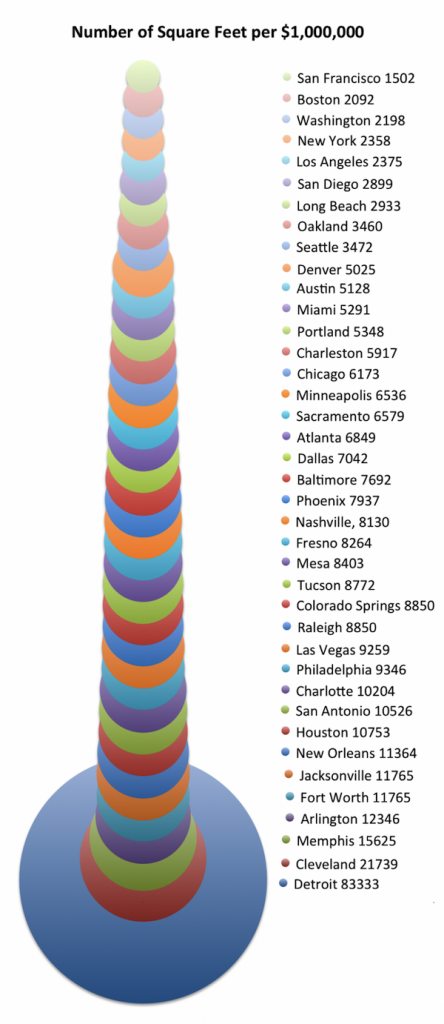

This matters a great deal, because mistaking the poverty problem for a housing market problem biases the political response toward some needlessly expensive and low-impact policies. Consider: Business Insider recently did a comparison of housing list price data from Zillow.com and Movoto.com to see how much square footage $1 million buys you in each of the major U.S. cities. Scan down the list, and keep scanning, until you finally see Philadelphia:

You can get about four times as much house in Philadelphia as in New York City or Washington, D.C., and even a bit more than in Baltimore.

The Philadelphia Real Estate Blog has pointed out that Philly’s median house price is “just about the lowest in the Northeast.” If you read the local business press, you’ll see all kinds of hilarious pro-landlord propaganda complaining about the city’s lack of rent inflation, like the recent classic “Why Rising Rents Are Not Bad for Tenants.”

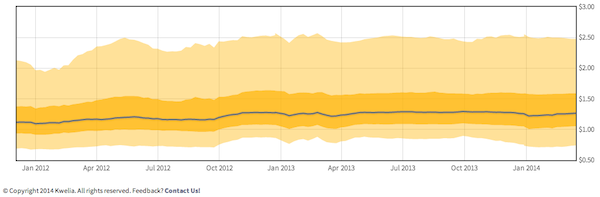

Indeed, as data from the real estate market analysis site Kwelia shows, rent growth in metro Philadelphia has been flat, even while population growth has been picking up the past few years:

Philadelphia is a huge land mass though, and looking at the citywide numbers doesn’t necessarily tell us whether we’re achieving the very worthy goal Clarke is concerned with: Keeping the areas where land values are appreciating inclusive for a diversity of incomes.

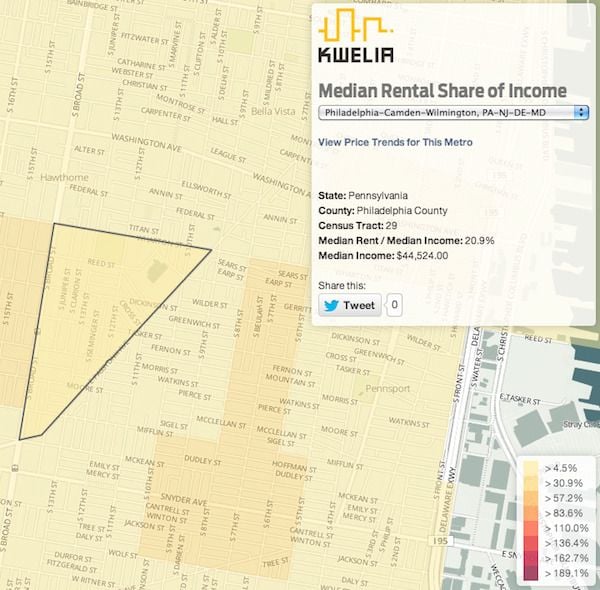

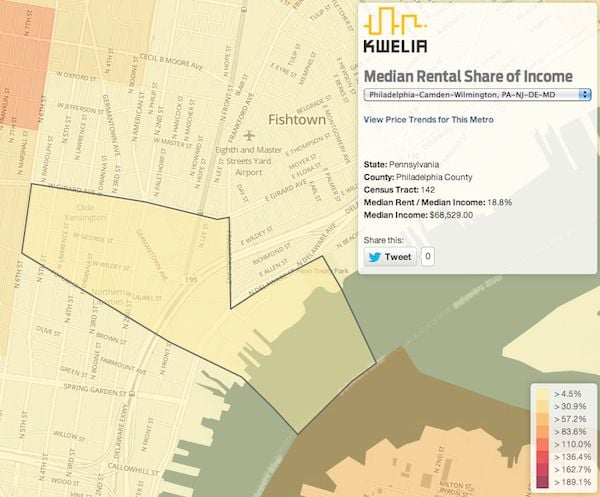

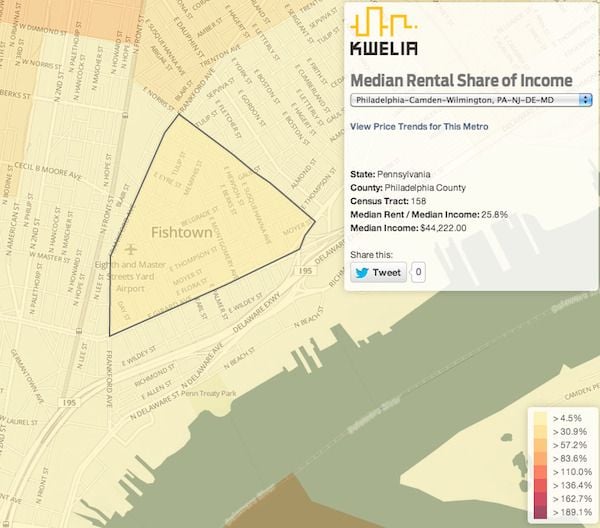

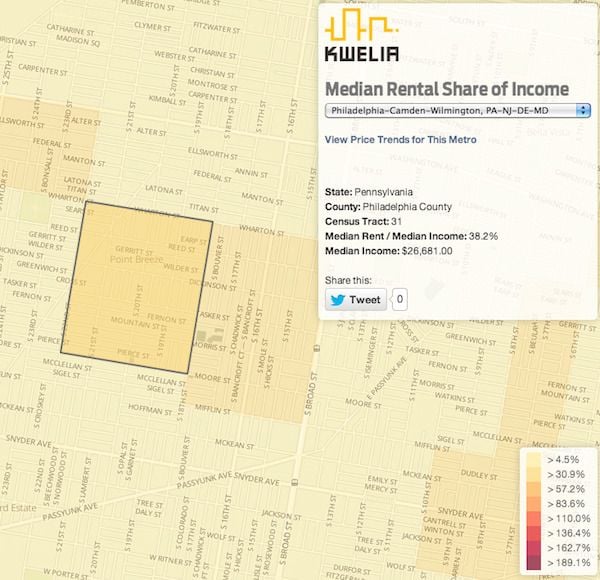

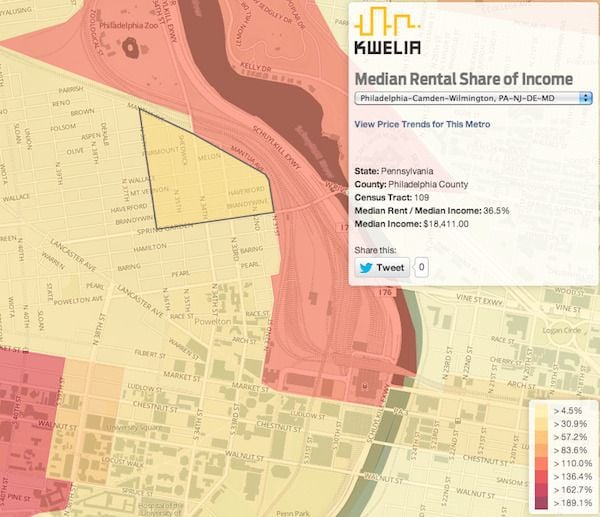

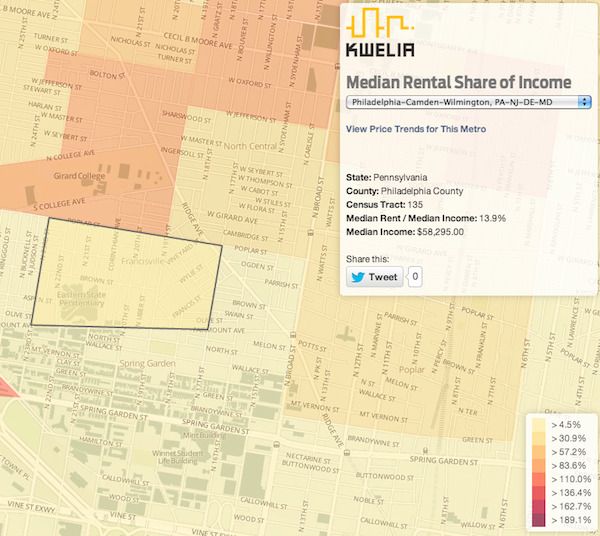

While the exact locations for Clarke’s “Opportunity Zones” have yet to be selected, the proposal specifically mentions Point Breeze, Francisville and Mantua. Is housing in these neighborhoods actually becoming unaffordable according to Clarke’s definition? I looked at this month’s Kwelia numbers and also added in appreciating neighborhoods like Fishtown, Northern Liberties and Passyunk Square for good measure.

Passyunk Square, a South Philly neighborhood that Food and Wine magazine says has one of the 10 Best Foodie Streets in America, has a median rent of about $1.32 per square foot — $924 a month for a 700-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment. If you make the median neighborhood income of about $44,500, you’ll spend about 21 percent of your income on housing.

Heads in New York and D.C. are exploding right now:

In Northern Liberties — which, to Philadelphians’ great annoyance, frequently draws comparisons to the Williamsburg hipster colony in Brooklyn — has a median rent of $1,078 for a 700-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment, at $1.54 per square foot. The median income in this Census tract is about twice the citywide median ($68,529), but the rent-to-income ratio is just 18.8 percent:

Fishtown, another poster child for gentrification fears just north of Northern Liberties, has a median rent of $1.45 per square foot, or $1,015 for a 700-square-foot one bedroom. That’s not a lot lower than in Northern Liberties, even though there are somewhat fewer amenities. But even with a lower median income of $44,222, the rent-to-income ratio is still just 25.8 percent — under Clarke’s threshold.

These three neighborhoods are some of the fastest-growing places in the city, and they’ve seen lots of nice amenities pop up very quickly, making them the go-to examples that many Philadelphians reach for when they want to rail against gentrification. But the data shows that housing in these neighborhoods hasn’t actually become unaffordable by Clarke’s 30 percent rent-to-income standard, even as these places have grown richer and more populous.

In Point Breeze, which has become the epicenter of Philadelphia’s gentrification debate, the median rent is only $665 for a 700-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment. But the median income is just $26,681, so even though the housing is really cheap in an absolute sense, it hovers just above Clarke’s affordability sweet spot with a 38.2 percent rent-to-income ratio:

There’s a similar situation in Mantua, where the median 700-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment is a fairly low at $966, but the median income is even lower ($18,411). This pushes the rent-to-income ratio up to 36.5 percent, outside the affordability range. Once again, however, that’s more of an issue with severely low incomes rather than high housing costs:

In Francisville, up near Eastern State Penitentiary and south of Girard College, the rent-to-income ratio is an impressive 13.9 percent. The median income is also much higher than the citywide median, at $58,295, and the median price of a 700-square-foot, one-bedroom is $1,225 — higher than in the other neighborhoods but still very low compared to how much square footage can be had for that amount in other big northeastern cities.

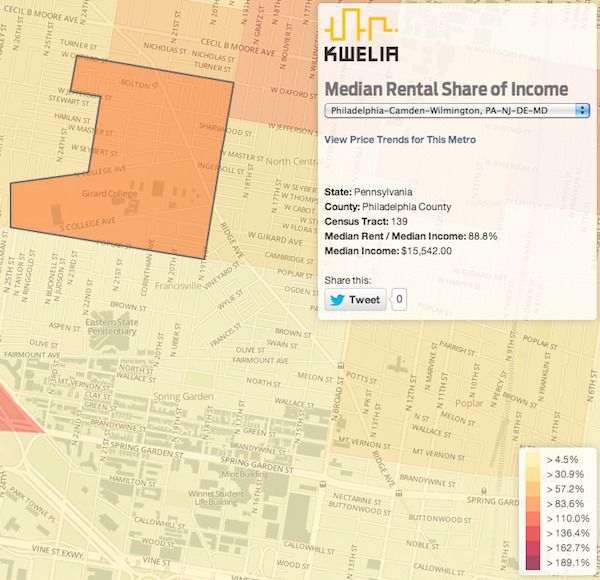

The Census tract to the north of this one really illustrates the extent to which Philadelphia has an income problem, not a housing affordability problem. Median rents are $1.10 per square foot, or $770 a month, for a one-bedroom apartment — pretty cheap. But the median income is only $15,542, which bumps the rent-to-income ratio up to 88.8 percent.

It’s not clear how much lower market rents could realistically go. It’s possible they could go lower, but a gap is likely to remain between what it costs to bring new housing units to market and what very low earners are able to afford. How should that gap be filled?

The city — whose options, to be fair, are constrained by the limited range of financial instruments the federal government has made available to help low-income people afford housing — could subsidize construction of new apartments, letting developers and the building trades unions take a chunk of the money before the public subsidy finally reaches prospective tenants. Or it could give people more money, so they can make up the gap between how much apartments cost and what they can actually spare from their meager paychecks.

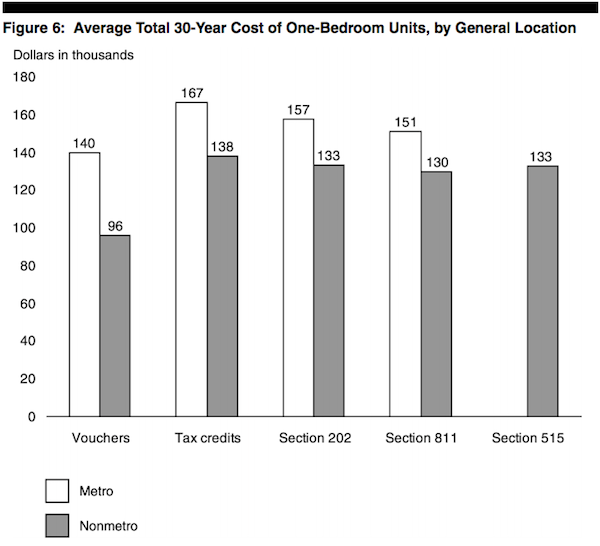

There is evidence to suggest public subsidies stretch further (sometimes a lot further) under the less prescriptive “give people money” option than under the tax credit-financed construction approach that Clarke favors. A 2002 Government Accountability Office study found that “compared with vouchers, the production programs cost from 8 percent more for Section 811 units to 19 percent more for tax credit units.”

Federal housing vouchers, though, aren’t always Moving to Opportunity vouchers, which allow lower income people to access housing in more economically integrated neighborhoods. And residential segregation by income is a big problem in Philadelphia — a key driver of metro-level income inequality — so it won’t do to compare Clarke’s plan to an idealized cash voucher program that doesn’t exist. Still, once city leaders see this as an income problem, not a housing affordability problem, some higher-impact local solutions can enter the discussion that don’t require major shifts in federal policy.

Back in 2012, City Council killed the late Councilmember David Cohen’s city wage tax rebate, a policy that passed in 2004 but was delayed several times by mayors John Street and Michael Nutter and never implemented. The rebate would have provided relief from the city wage tax for Philadelphians making less than twice the poverty line — about $35,000 for a family of three, exactly the people who need targeted help from the city. A three-person family making $25,000, for example, pays about $950 a year in city wage taxes. The rebate was projected to cost about $22 million a year out of a $4.5 billion budget.

This would put more money directly into the hands of low-income Philadelphians and help them afford their monthly housing costs, rather than running the money through a gauntlet of grasping special interests first.

A more promising option would be for City Council and the Nutter administration to follow the lead of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which factors transportation costs into its housing affordability equation. A house in the middle of nowhere is really cheap, but if you have to drive two hours into the city for work every day, all of the money you save on housing will go toward gas and car maintenance costs. Alternatively, you might pay higher rent to live in a more central location, but that means you could likely save money one commuting costs.

Housing and transportation are the top two largest expenses for the typical American family, so an affordability measurement that considers these costs in concert will better identify problem areas than one that considers housing costs in isolation.

Look up some of the neighborhoods that the “1,500 New Affordable Housing Units Initiative” targets on the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s H+T Index map, and you’ll see that they’re even more affordable than Kwelia’s data showed, being relatively close to transit connections or located within a reasonable walking distance of jobs near Philly’s main employment clusters in Center City and University City.

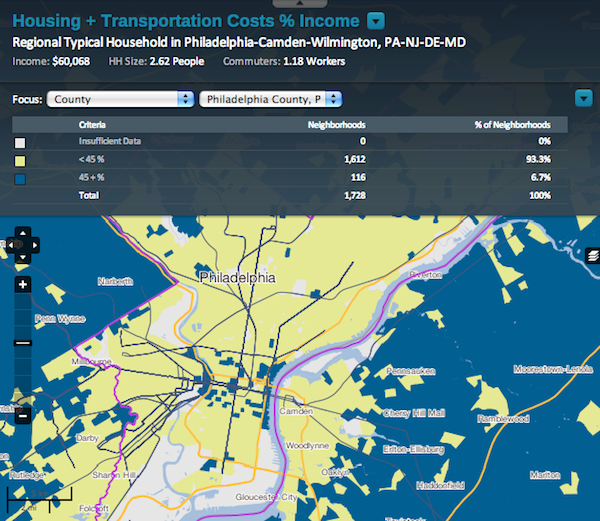

CNT puts the housing and transportation affordability threshold at 45 percent of the Area Median Income. Using this metric, it finds that 93.3 percent of the “block groups” in Philadelphia County are affordable when transportation costs are factored in:

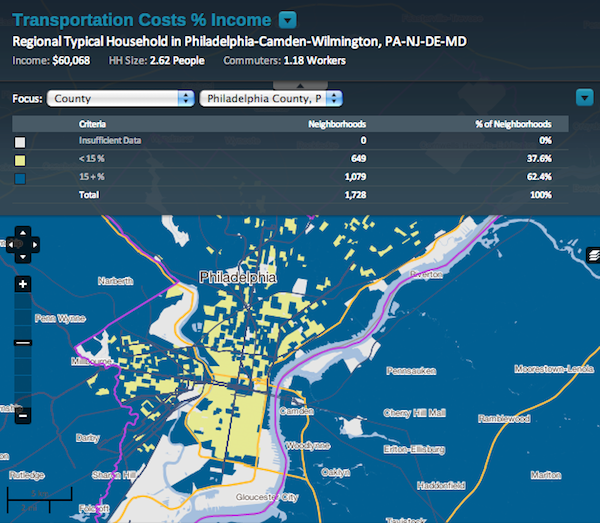

Interestingly, housing is actually pulling more than its fair share of the weight, because most block groups (62.4 percent) have transportation costs above the recommended 15 percent of median income:

That’s not surprising given Philadelphia’s strangely high 50 percent car ownership rate. If there is an affordability problem to be addressed on City Council, it has to do with transportation.

Jonathan Geeting is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia, where he writes about land use and public space politics. His work appears at Next City, This Old City and Keystone Politics.