After decades of population loss, many of Detroit’s neighborhoods are faced with an overabundance of vacant lots where houses once stood. Even the city’s healthiest, densest areas aren’t immune. Over 23.4 square miles of the city — 16.8 percent of Detroit’s total area — is vacant land, and that excludes parks and rights of way. That number is expected to exceed 30 square miles as anti-blight demolition efforts are realized.

But tearing down neglected houses only addresses blight in the short term, as the lots that are left behind can quickly become overgrown and attract illegal dumping.

“What many folks have come to recognize is that the city has a tremendous supply of vacant land that contributes to blight and works to destabilize neighborhoods,” says Dan Kinkead, acting director of the implementation office of Detroit Future City (DFC), a nonprofit that created a strategic framework for Detroit’s long-term development. “We have vast areas of the city with moderate vacancy. These are also places with high concentrations of children and elderly people. These are places where quality of life needs to be improved.”

The problems associated with vacant lots stem from a lack of stewardship. While the city has made efforts to encourage residents to become stewards of vacant land over the years, most notably through an initiative that sells side lots for just $200 to adjacent homeowners, few tools have been in place to help those buyers care for lots in a sustainable way. But today, Detroit Future City released “Working With Lots: A Field Guide,” one of the first aids for residents and community groups that are caring for and beautifying lots in their neighborhoods, transforming them from liabilities into assets.

With a grant from the Erb Family Foundation, DFC has printed 2,000 copies of the guide that will be distributed throughout the city and will be available to residents at the 23 branches of the Detroit Public Library. A website was designed to complement the booklet.

To make the guide accessible to everyday Detroiters — and not end up with a wonky manual intelligible only to landscape architects and urban planners — DFC brought in The Work Department, a Detroit-based design studio, to help engage the residents and stakeholders who ultimately will be the users. “We’d receive a technical document, then we would attempt to translate it into something residents could more easily understand,” says Nina Bianchi, a partner at The Work Department. “We have a history of building toolkits.”

Over the course of a year, the firm and DFC facilitated monthly workshops with residents and representatives of over 50 Detroit-based organizations that would serve as a sort of focus group for refining the guide. Some workshops examined seemingly simple tasks, such as arriving at a shared definition of green infrastructure, while others involved getting direct feedback from people on what would go into the guide and appear on the website. For example, 75 lot treatments were originally proposed to appear in the guide, but residents said that was too much.

“The residents were integral in helping us decide which treatments would make it into the guide,” says Libby Cole, a partner at The Work Department.

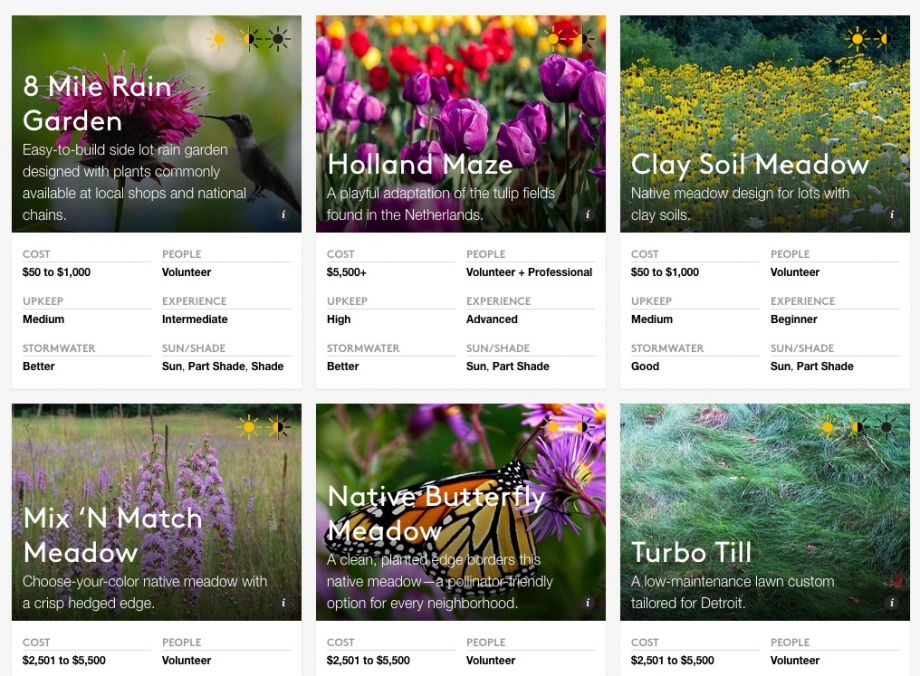

“Working With Lots: A Field Guide” offers designs for Detroit’s vacant lots. (Credit: Detroit Future City)

Using the Guide

“Working With Lots” serves as a sort of workbook, outlining 34 lot designs — from a “Dumping Preventer” to a “Soil Builder” to a “Party Lot” — and detailing the type of people, the amount of experience, and money needed to realize them. Each treatment’s upkeep requirements and stormwater benefits are also described.

But before it asks residents to think about specific lots, the field guide asks them to think about their communities and neighborhoods. “Really, it’s about bringing people in neighborhoods together to address challenges,” says Kinkead.

The first activities in the book asks users to identify neighborhood hubs and list possible collaborators before sketching or describing what kinds of landscapes they would like to see. Others involve taking inventory of a block’s human resources and physical attributes.

Then the activities become more site specific.

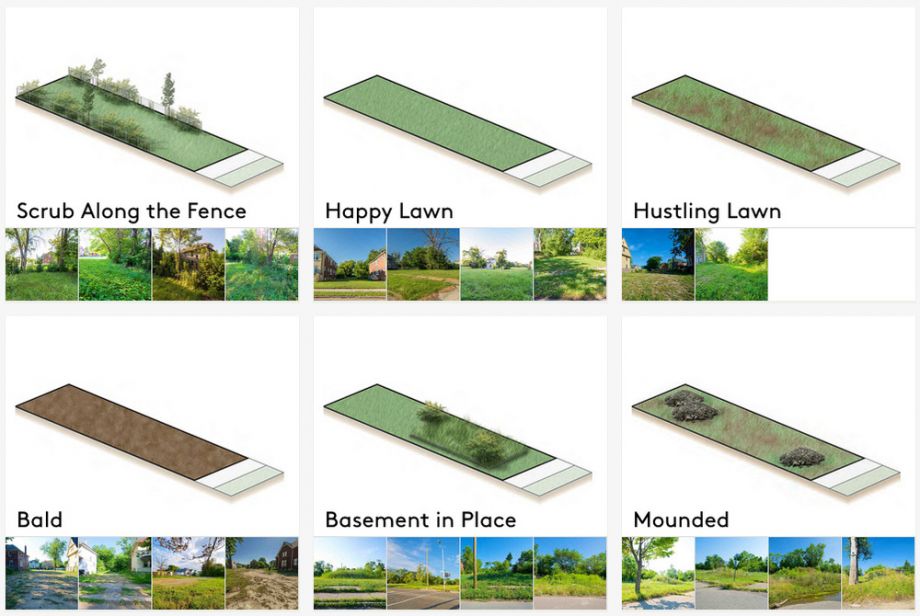

“All vacant land is not the same,” says Erin Kelly, innovative landscapes manager at Detroit Future City and a landscape architect. “The idea is to match designs to existing conditions.”

Users can identify what type of lot they are working with by using the “Discover Your Lot” tool on the website. From there they can select the best possible design type for that lot, though DFC encourages mixing and matching.

Taking into account that not all vacant lots are the same, “Working With Lots: A Field Guide” helps Detroit residents identify what type of land they are dealing with. (Credit: Detroit Future City)

“Customization is an important part of this,” says Kelly. “We intentionally did not include food production in the guide because of all the great work happening in the city in that area, but we’re excited to see how people integrate that into these designs.”

Finally, “Working With Lots” and its website contain a directory of resources and organizations that can help residents realize lot designs, including government agencies, nonprofits, service providers and landscape supply retailers. “Identifying the gaps [in services and retailers] has been interesting because they show opportunities that exist to create local wealth through new businesses,” says Kelly.

As residents and community groups begin to use “Working With Lots” to realize their visions for vacant land in their neighborhoods, DFC will begin the storytelling component of the project. Users of the guide will be given lawn signs to mark project sites and will be encouraged to share images of their work on DFC’s website and social media.

While the amount of vacant land in Detroit is expected to grow for the foreseeable future, “Working With Lots” will help assure that blight does not grow with it. And the process of creating such a tool is something other cities can learn from. “The methodology that this uses is applicable to a range of cities dealing with vacant land issues and depopulation,” says Kinkead.

Learn more about “Working With Lots: A Field Guide” here.

Matthew Lewis is a freelance journalist living in Detroit.

_600_350_80_s_c1.JPEG)