A promising swath of real estate runs through Seattle, between the forest of cranes rapidly densifying the downtown core and the hip kingdom of Capitol Hill — promising, but underutilized.

“It’s probably the most expensive piece of dirt between Vancouver and San Francisco,” says Chris Patano, director of Patano Studio Architecture. “And we’re using it to drive cars on.”

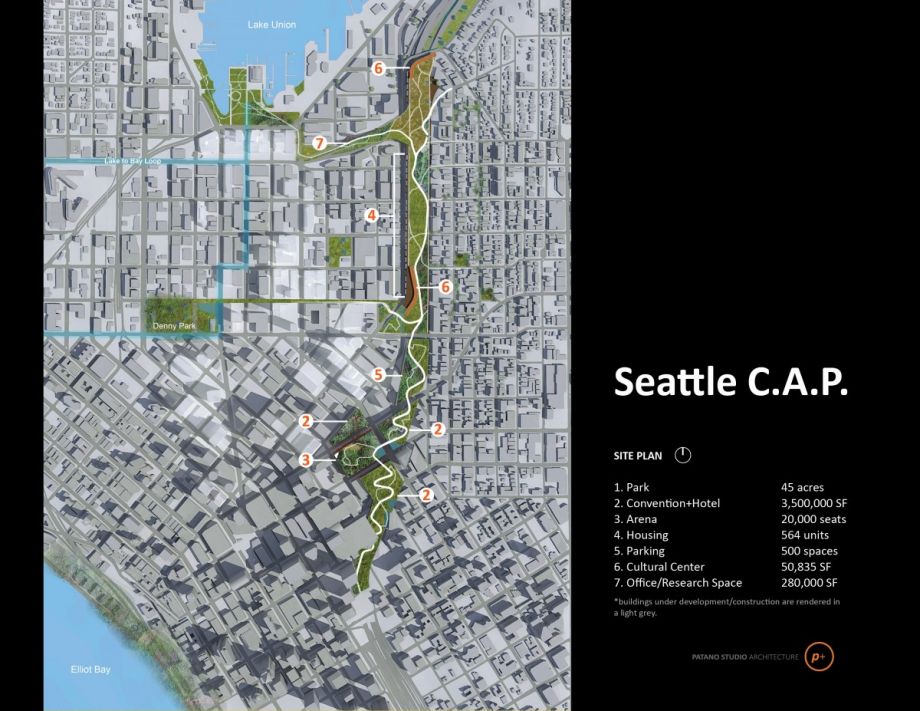

That dirt is Interstate 5, a steep, noisy canyon that divides some of the city’s fastest developing neighborhoods. Patano and his studio want to knit Seattle back together by capping the freeway with a two-mile-long, 45-acre park.

They call their proposal Seattle C.A.P. It’s a High Line for an existing transit corridor, a central park for a city with few grand public gathering places. And Patano thinks, ambitious as it sounds, that it could actually happen. His design inspiration has personal roots: He used to live near I-5, and his windowsills would get dusted with black grime, the particulate matter of pulverized tires.

Only five street connections cross the freeway between the First Hill neighborhood and the southern end of Lake Union. It’s this section — largely below the grade of the surrounding city — that Patano and his studio have in mind to cap. They see a park atop I-5 solving myriad problems at once: reconnect the severed urban fabric, reduce noise and air pollution, manage stormwater, and create some affordable housing.

Aerial rendering of the C.A.P. (Credit: Patano Studio Architecture)

In renderings, the cap is a river of trees. Patano has modeled the southern end of the park rising to a peak — not unlike the hills being constructed on Governors Island in New York — that would mirror downtown’s towers and pay homage to Seattle’s naturally hilly topography.

From there, the park would slope down to a relatively flat grade, becoming a more traditional Olmstedian park as it heads north. A winding trail would run through it, with multiple pedestrian and bicycle connections to the street. Where the western edge becomes elevated near Lake Union, a sheer wall would enclose the freeway. Patano envisions building affordable housing there.

Rendering of proposed affordable housing on park’s northwestern edge (Credit: Patano Studio Architecture)

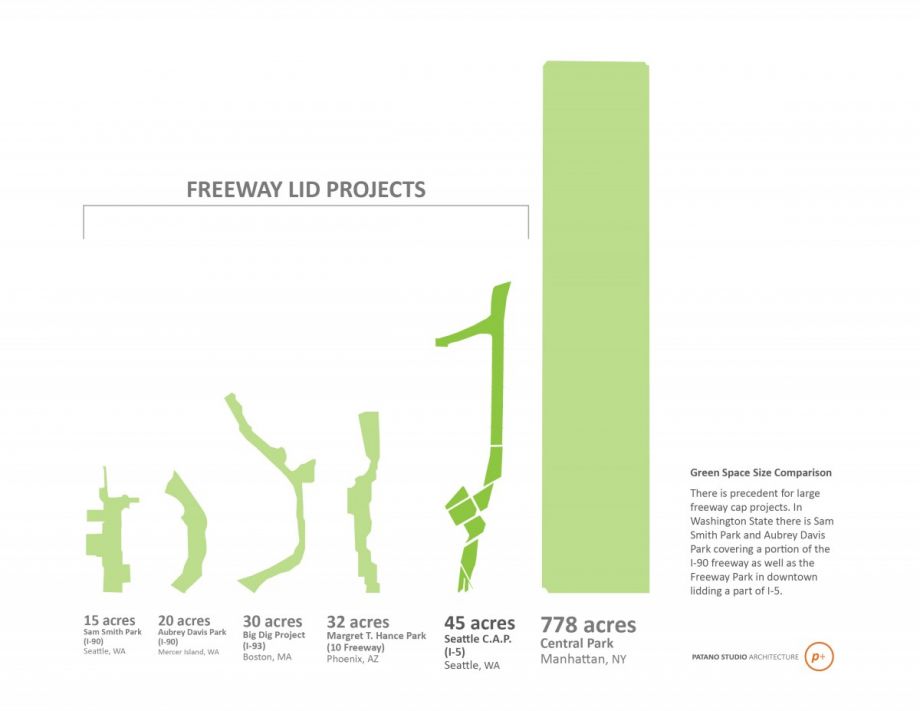

The C.A.P. would be far from the first of its kind. Boston covered a highway with the Big Dig. Dallas has Klyde Warren Park. And Seattle has actually been a leader in this field before. Just south of where the proposal begins is the 5.5-acre Freeway Park, recognized by the Cultural Landscape Foundation as the first park built over a highway.

Patano isn’t the first to propose such a concept for I-5 either. Much of his studio’s work was informed by the graduate thesis of Scott Bonjukian. An independent group had been working on this idea for nearly 10 years by the time Patano began. He says the rapid densification of the city is making the project seem more necessary every day. The studio’s renderings have helped too. “Talk doesn’t get people inspired,” says Patano. “We’re visual creatures, we can see something and understand it.”

(Credit: Patano Studio Architecture)

What distinguishes the C.A.P. from other proposals is its scale and complexity, which Patano thinks actually make it more plausible and timely. “Complexity solves multiple issues,” declares one of his PowerPoint slides on the design. Despite the wave of rapid development, Seattle is still tackling projects just one at a time. “We really want to promote that we have to think citywide, at a city scale,” he says.

For now, there’s just a vision. Seattle’s DOT has been receptive, as have other city agencies, while the state DOT has generally dismissed the project on basis of further traffic congestion and cost (which Patano estimates at roughly $800 million).

To move forward, the C.A.P. needs funding, support and a team: landscape architects to program the park in more detail, engineers to design air circulation and scrubbing for the now boxed-in freeway.

But as for why the city needs this project, and why now is the time to do it, Patano needs no assistance.

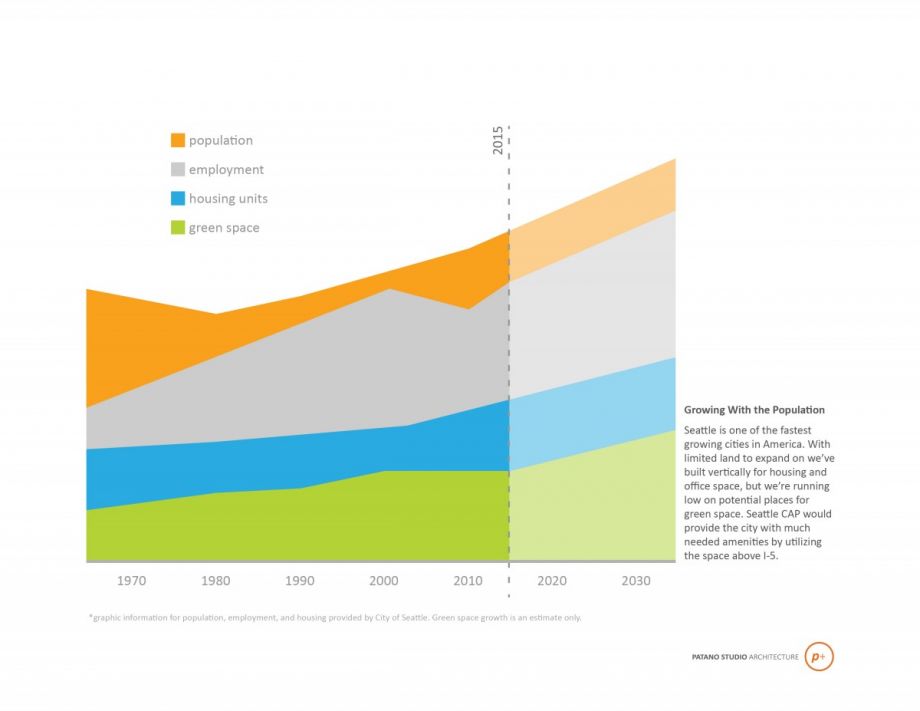

“We’re starting to see a really dense city, a city that perhaps isn’t working for all of us the way that we want it to,” he says. “You can’t walk around now and not feel the pressures that are occurring.” There’s more traffic, housing is harder to find. And there’s this graph, showing Seattle’s population, employment and housing units rising steeply — and its green space, flat since 2000.

(Credit: Patano Studio Architecture)

As condos go up, potential locations for a Seattle central park are dwindling. Capping I-5 could be the city’s last chance. Patano believes a timely confluence of events could make it possible.

First, the Washington State Convention Center, which already partially bridges I-5, is planning an expansion for 2017. Why not further cap the highway, and put in the first piece of park at the same time?Second, Seattle is clamoring for (yet another) stadium. Instead of building the new basketball/hockey arena in the SoDo neighborhood — beside the city’s two existing stadiums — why not fold it into the convention center? The arena could even sit underneath the hill at the park’s southern end.

Third, and most importantly, though Washington DOT is loath to talk about it, I-5 needs to be rebuilt altogether. Designed in the mid-20th century to outdated standards, the highway is no longer suitable for seismic stability, and will need to be replaced in the next 20 years.

This is probably the last thing Seattle residents want to hear, with the city already in the midst of a major, stumbling highway replacement project. But the eventual reconstruction of I-5 could be the perfect time to implement the C.A.P.

Before that happens, says Patano, the city needs to secure the air rights to develop atop the freeway. That will take political work on the part of city residents, something they seem prepared to tackle as the proposal gains momentum and a 50-year-old eyesore becomes less bearable every day. “It’s just like everyone woke up one morning and said, ‘Wow, this sucks,’” says Patano. “‘We should do something about this.‘”

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)