Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberDr. Bon Ku, like many Americans, grew up without health insurance. The son of Korean immigrants who bounced from Chicago to Houston before landing in Elizabeth, New Jersey, he spent his adolescence working in his family’s restaurant, bussing tables and washing dishes alongside undocumented workers. Like him, they were living on a knife’s edge, hoping to not get injured or sick.

It was this experience that led Dr. Ku, decades later, to the emergency room. “My experience of not having health care and just being really poor, working with illegal aliens in the restaurant in the basement in Newark, New Jersey, in a kitchen,” he says, “that’s one of the reasons why I went into emergency medicine — it’s really developing empathy for the marginalized or the vulnerable in our society.”

Growing up in this environment, where the abstraction of health care meets the cold reality of urban life, is what led Ku to develop a more city-focused view of medicine than most ER physicians. Between pulling night shifts at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia and teaching at their medical school, he co-founded JeffDESIGN, a hybrid university program that combines medical training with design classes. Ku, who sports clear-framed glasses and slicked-back hair, transitions seamlessly from scrubs to chambray button-downs. If you saw him on campus, you’d think he was, well, a design professor.

Studying through JeffDESIGN is like majoring in medicine and minoring in design. Launched in February 2015, the program focuses on a broad range of design applications aimed at impacting real people’s health, from 3D printing that will help improve surgery to redesigning the physical space of hospitals. Most importantly, it’s about exploring the ways infrastructure, community and the built environment can have a positive impact on health.

“One of our mission statements is, how do we design healthier cities?” Ku says. “And how do we humanize the data around that? Some people argue that’s not the health system’s job, that’s a public sector job. Because if you fix economic disparity and the quality of education and food, that’s going to improve health, totally. How can I, as a physician who deals with the complications of diseases, make an impact on that? I want caring about these disparities and social injustices to be in the DNA of physicians.”

Ku originally majored in classical studies at Penn, trying to, as he explained it, resist his parent’s Asian-immigrant dream of having their American-born son go to an Ivy League school and become a physician. But his literary fantasies quickly faded.

“I was like, ‘I’m never going to make a living doing this,’” he laughs. “Then I found the ER is a great way to be able to serve these populations that I was interested in working with.” He went to med school at Penn State and did his training primarily in urban emergency rooms before moving back to Philly and starting his career in the ER.

But the health care system’s failure to adequately serve the many low-income patients he treated in Philadelphia left Ku disillusioned. He wondered, how could he make a bigger contribution to public health? He took a year off and went to public policy school at Princeton, where he toyed with the idea of someday going into politics. However, his time away from Philadelphia ultimately reinvigorated his love for the emergency room and changed his view of the impact a physician could have — not just on patients, but on the places they lived.

“I’ve always felt like the creative part of my brain has been trapped, and a lot of these kids feel that way,” he explains. “Because I think we could do more. And so having something as loose as design allowed me that canvas to be able to go, ‘Okay, we get to work on all types of design,’ whether it’s working with architects and thinking about design of the built environment to designing medical devices. Looking at it from that sort of lens and mindset opened up huge opportunities for us.”

A couple of years after he returned to Philadelphia, Ku helped cofound JeffDESIGN as the first-of-its-kind design track within a medical school. The medical school’s dean, Dr. Mark L. Tykocinski, mentioned to Ku he had a vision of medicine intersecting with fields outside of standard medical school study, like humanities or computational engineering. They settled on a co-curricular design program within the medical school and JeffDESIGN was born. Its goal was to design healthier cities, find more efficient ways to deliver care and develop the next generation of medical devices. It’s not a bunch of heady undergrads touting the beauty of Copenhagen’s streetscapes — it’s a program that aims to arm a new crop of doctors with a modern set of tools to address public health through design.

Deep beneath Philadelphia’s old Federal Reserve building in Center City, in a steel-encased former bank vault, JeffDESIGN students have been working at the intersection of medicine and design since November 2016. They spend their days 3D-printing models of jaws, mapping inefficiencies in hospital layouts and studying how to redesign urban spaces for public health. The 4,000-square-foot laboratory space is simply called The Vault. When I was there on a Friday morning late last year, Ku and I lounged on a couch in the back corner while students tinkered with 3D printers and teased Ku that they know more about The Vault’s technology than he does. Photos and mockups of various projects were plastered on walls and easels throughout the space.

One of those projects, smarterPLAY — they have a penchant for ALL CAPS — explored the way children play in parks, playgrounds and other public spaces. Last summer, JeffDESIGN researchers slapped sensors on groups of kids across Philadelphia and monitored them in a variety of locations, from the Waterloo Playground to the Whitman Branch of the Free Library. The goal was to see how exactly they used the spaces in an effort to understand how they might be redesigned to attract more people.

The data from smarterPLAY, as Next City reported in an op-ed last fall, “resulted in hundreds of hours of quantitative data about the physical activity and location of users, both indoors and out. The data is anonymous and helps create an accurate picture, down to a few centimeters, of where people go, how much time they spend there, how active they are and what interactions they have with equipment, site features or other people.”

Dr. Bon Ku stands inside The Design Lab, also known as the The Vault, which once held the money for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia on Chestnut Street.

It might seem trivial, monitoring the way kids use a jungle gym or gallivant across the pavement in the dead heat of summer. But parks — where they are and how they’re used — have a measurable effect on a neighborhood’s well-being. A 2016 study from Environmental Health Perspectives found that proximity to trees planted along streetscapes, parks and various other forms of “greenness” lowers mortality rates. And part of a 2011 report from The Trust For Public Land explored how important design is: “It may seem odd that design could be related to health, but it’s true: pleasing predictability encourages participation. If the basics are well provided, people will flock to the system and use it to the fullest.”

This is how Ku and his students in Philadelphia can have an impact on health outcomes, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. “As important as access to care is the access to safe and healthy places for our kids to play,” Ku explains. “We don’t think of playgrounds as public health interventions. I’m trying to change the language around that and change our mindsets around playgrounds. These are health-promoting activities, these are going to make our communities healthier. And also apply the rigor of the data science that we apply to operations and pharmaceutical. Bring that rigor into it and go, this is not fluffy stuff.”

Lariq Byrd was caught in crossfire on the day after Christmas in 2015. The bullets struck his spine and left him tetraplegic. The following fall, Ku brought the 16-year-old Philadelphia native into his Design for Disability class. Students were tasked with imagining new ways to make life more livable for those with disabilities. A poet and athlete, Byrd wanted to write with pen and paper and play sports again.

JeffDESIGN students worked with Byrd to develop solutions tailored to his needs. They designed a Nintendo Wii remote that attached to the 16 year old’s wrist with Velcro and mounted buttons in his wheelchair headrest. Another group built a skate in which Byrd could rest his forearm to help stabilize his arm while writing. Yet another group built a modified headrest with built-in speakers to hold an Amazon Echo Dot to help him communicate.

But it was the human interaction that had the largest impact. Pennsylvania-state Medicare doesn’t cover home modifications for a child without cognitive disabilities. Byrd’s family could not afford to spend $20,000 to install a new wheelchair ramp at their home, and they did not qualify for government assistance. Every time he had to leave the house, it took at least two people to get him to the sidewalk.

Ku was in Austin for South by Southwest where he and JeffDESIGN co-director Robert Pugliese met with Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney. They told the mayor they were working with this wonderful kid, but that the policy issues were stacked against his family.

“So the mayor was like, ‘Send me an email, I’ll take care of it,’” Ku says. “And we’re thinking, ‘This shit’s never going to happen.’ But we sent him an email, then a month later he got a motorized wheelchair ramp…It’s this small win, but it’s really kind of connecting the dots where we understand the needs of people living in those communities. We have these partners that allowed us to connect to Lariq, and we had this access to the mayor and the city in bringing awareness to an issue. So we’re hoping to do that on a bigger scale — not just impacting one person, but impacting neighborhoods and communities and cities.”

The built environment itself can influence both physical and mental health. Whether it’s blighted blocks or a lack of trees, the way cities are designed is as much a public health concern as food deserts or access to health care facilities. Ku, who has spent the majority of his career treating patients who come from low-income neighborhoods, emphasizes this with his students.

“It’s a toxic stress on those people living in those communities. It physically impacts them,” he says. “And so it’s a huge opportunity to think about, you know, we’re not just making pretty spaces. We’re trying to get rid of these toxic stresses in their community by activating and transforming these spaces.”

A 2017 report from the Urban Institute examined how the built environment — and blight in particular — affects public health. The writers combed through reams of studies and found that everything from vacant lots to substandard housing can have negative effects on both physical and mental health. “Poor conditions in homes and neighborhoods can have a compounding effect on the health and welfare of low-income individuals,” it reads.

The numbers bear that out. In Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, where the median income is $16,500 and the unemployment rate is 52.6 percent, according to a study by Virginia Commonwealth University, the average life expectancy at birth is just 69. “That is an ultimate mark of disparity when you physically die earlier,” Ku says.

Researchers have even found that heart rates will go down when people simply walk past green space that have been added and blight cleaned up. “People were having a biologic stress response,” explains Dr. Charles Branas, chair of Columbia’s epidemiology department who has spent years studying blight and urban health. “People were also telling us that they purposely avoided these spaces. Even if it was a longer walk to school or a longer walk to the bus stop or the train station, they would take the route that did not go past these sorts of abandoned, vacant and blighted spaces.”

It’s no secret that addressing blight can, in many cities, help reduce crime, but academics like Ku and Branas are trying to change the thinking around how environment can impact health. The built environment is as much a public health concern as it is an infrastructure need.

“These kids are all going to graduate as physicians, and they’re going to have a whole new language that nobody who’s ever graduated from a med school has had before.”

“So if you have a block that has perhaps 40 houses,” Branas says, “imagine that half those houses are abandoned, have fallen in disrepair, or have been torn down and are now vacant lots. If you can, in a very short period of time — perhaps less than a month, maybe a few weeks — remediate and make those abandoned spaces into something positive for the community … perhaps a parklet, perhaps cleaning up the building, what we’re finding is that this has a significant impact on reducing things like depression and improving mental health by a number of known mental health indicators.”

Parklets are not going to erase food deserts or magically improve the health outcomes of every resident in North Philadelphia or Southwest Detroit or Chicago’s South Side. But, their installation can signal to lawmakers that chipping away at ruin or improving access to green space in under-served areas is a two-pronged investment that enhances both infrastructure and public health.

These types of improvements don’t require large amounts of cash, either. “The first thing I’ll tell you is this doesn’t need to be expensive,” Branas says. “Stop trying to install luxury-built amenities that people in neighborhoods below the poverty line need to travel long distances to use. Build straightforward-but-useful amenities right in the neighborhoods they live in. … The return on investment is anywhere from $25 to hundreds of dollars for every dollar invested in these sorts of things.”

At JeffDESIGN, Ku is trying to impart this on the next generation of physicians. They will still read x-rays and treat kids with broken collarbones, but they’ll also be able to more broadly impact public health by influencing the way cities are built or retrofit.

“These kids are all going to graduate as physicians, and they’re going to have a whole new language that nobody who’s ever graduated from a med school has had before,” Pugliese says. “So that when they’re being tasked to think about how to help to improve this community, they at least know how to have the conversation about the upstream causes of these health outcomes.”

Ku’s vision was shaped in the emergency room. He did part of his training at the Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx and has spent his career working in urban ERs. That means fewer broken ankles from soccer games and more repeat visitors for whom the ER is their only option.

A 2013 study published in Health Affairs suggests as much. “Patients with low socioeconomic status use more acute hospital care and less primary care than patients with high socioeconomic status,” researchers found. For many low- and middle-income Americans, the ER is primary care.

“What I love about emergency medicine [is] we’re the only specialty that has a federal mandate that we have to see all patients regardless of ability to pay,” Ku says. “We have an unfunded mandate to take care of all comers. Because of that we serve as a backbone of our healthcare system. And I get to see the people I work with, you know, illegal aliens, the poor, and people who can’t afford insurance who end up showing up at our doorstep.”

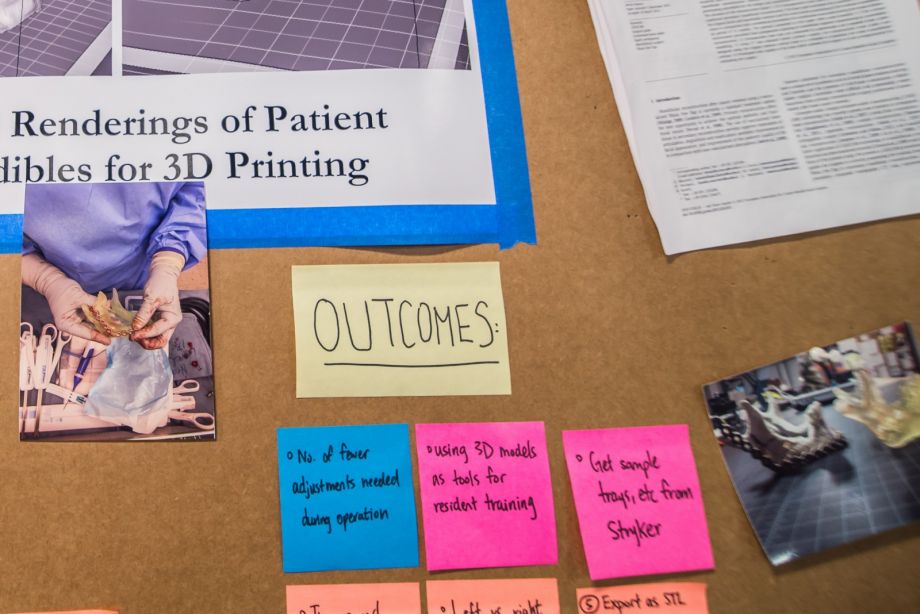

A board in the Design Lab helps Dr. Bon Ku and his team organize and plan their various projects.

The ER, Ku tells me, is “the barometer for health of communities.” He says his emergency room work connects him to Philadelphia in a more meaningful way than serving as a legislator might. This is JeffDESIGN’s ethos: You don’t have to leave the day-to-day work of medicine to change these larger trends. You can, as Ku says, work and observe from within.

“I’m in the mess of the healthcare system. I see what happens to a patient that does not have insurance. I see the urban homeless,” he says. “People from all over the city come to Jefferson, from South Philly, from North Philly. And I always ask patients, ‘Where have you come from? What neighborhood do you live in? And how are you going to get home?’”

But it’s the repeat visitors who often come in the middle of the night that have influenced the way he now thinks about medicine and public health. Whether it’s a diabetic or someone dealing with addiction or a single mother who works 70 hours a week, the emergency room has given Ku a holistic view of the city’s health. It has changed the way he thinks about patient care — and about what design means.

“I think at the core of human-centered design or design thinking is deep empathy for the end user,” he says. “So it’s allowed me to kind of pivot to the question of understanding the needs of patients and develop a skill set.”

Part of what Ku and his team are teaching at JeffDESIGN is that, as physicians, they can help change health outcomes through design choices that will hopefully become mainstream policy wisdom. Physicians are not architects or city planners, so part of their job must be to influence those who do make the decisions that shape neighborhoods and communities.

“One of the things that we’re finding is that definitely there’s no silver bullet,” says Dr. James Sallis, distinguished professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at University of California-San Diego. “There’s no one fix to any of this. And what we keep seeing over and over again is if you want a healthy neighborhood you have to work at it. And just putting in a sidewalk is not really going to do much. Or just putting in some little trees is not really going to do that much. Or even adding a park is not going to transform the neighborhood, in that you need to do all of those things. And I think of it as, you need to create a whole community, the whole picture, the whole system.”

Ku is trying to translate what he has learned in the ER for a future generation of doctors. His students are thinking outside the box and spearheading projects like smarterPLAY that have the potential to positively impact the way we design neighborhoods. But it is an immeasurably difficult task. Public health, particularly in low-income American neighborhoods, has vexed lawmakers and health workers for decades. A design competition isn’t going to fix a food desert, and a couple of trees aren’t going to curb obesity.

But if doctors have a voice in design, it can help shift the way we build our cities. Branas continually emphasizes that policymakers need to simplify their thinking. It’s less about the next big shiny project and more about equitable access to green space.

“You need to change the basic structures that are contributing to this in the first place,” he says. “Kids or anyone are not going to use parks that are a decent distance from their home. Access and getting there quickly and easily is probably the best opportunity.”

Students at JeffDESIGN aren’t spreadsheet jockeys; they do field work and talk to people, combining traditional research methods with community outreach. As part of their Health Insights 215 program — a collaboration with TD Foundation and The Food Trust, a local nonprofit food access advocacy organization — they’ve set up pop-ups at farmers’ markets throughout Philadelphia and canvassed locals about the health challenges within their community.

This spring, JeffDESIGN is buying an Airstream, gutting it, and redesigning the trailer as a mobile classroom and tech lab. Called CoLab Philadelphia, it will launch in late spring or early summer. It’s an extension of what they learned with Health Insights 215 and an opportunity to have an immediate impact on the city’s citizens. “It’s about creative placemaking in the city,” Ku says. CoLab will partner with various nonprofits and organize pop-ups in lower-income neighborhoods to offer everything from medicals services to access to fresh produce. The hope is that CoLab will be nimble and able to take on different forms as the students see fit.

“We try to go into the city, into the neighborhoods and reach out to these communities and think about ways where we could look at the built environment,” Ku says, “and try to make an impact on some of these communities. But one of the long-term fixes is, how do we, when we think about the future of medicine, redesign what a doctor does?”

There is no perfect answer. Ku knows that it will be a long time before the work they’re doing now has nationwide impact. He and his team are trying to change the way doctors think and influence public health in cities. He’s knows what he’s up against; he knows they can’t change cities overnight.

“It’s a 20-year process,” Ku says. “So I love what I do. I get to shape the future of medicine, and this is a long-term strategy. These guys aren’t going to be done with their training for another 10 years. … But now it’s like the system’s blowing up. I mean, it’s totally blowing up. So I want to give the future physician that ability to work within the system. We don’t even know what it’s going to look like.”

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.

Joshua Scott Albert is a Philadelphia-based photographer and reporter. He's contributed to VICE, Buzzfeed, Philadelphia Magazine and several other outlets.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine