When Barbara Griffith-Wilson thinks of Flint’s future, she sees riverside parks, inner-city fishing piers and wide-open green spaces where houses and factories used to sit. A longtime community activist, Griffith-Wilson helped draw up Flint’s new Master Plan, its first since 1960, back when the Michigan city was home to 196,000 people working in half a dozen General Motors factories.

“I really wanted urban spaces, open spaces,” Griffith-Wilson said. “For years, I’ve been a person who wanted to make this area beautiful.”

Griffith-Wilson lives on the South End of Flint, near Thread Lake, which the plan designates as Community Open Space set aside for recreation such as fishing and boating. Elsewhere, Flint aims to make an asset out of one of its least appealing qualities — acres of vacant land — by transforming its emptiest quarters into green neighborhoods which will eventually be given over to parks, agriculture and alternative energy projects like solar panels and wind farms.

“If you go through some of those neighborhoods on the East Side, I think that we probably could do some farming,” Griffith-Wilson said. “I think we’re going to need some food sources, and I don’t see anything wrong with hoop houses.”

The Master Plan is a new blueprint for urban life in Flint. An auto-making town with a housing stock of mostly small wooden bungalows and Cape Cods, Flint was built for a blue-collar workforce raising families on 40-by-100-foot lots not far from the factory. Those factories don’t exist anymore, and many of the families have long since fled for bigger houses in nearby suburbs.

“The city’s circumstances are radically different than 50 years ago, before suburbanization and globalization,” Flint Mayor Dayne Walling said. “Flint boomed as a one-size-fits-all industrial city, and the 21st century is completely different from that.”

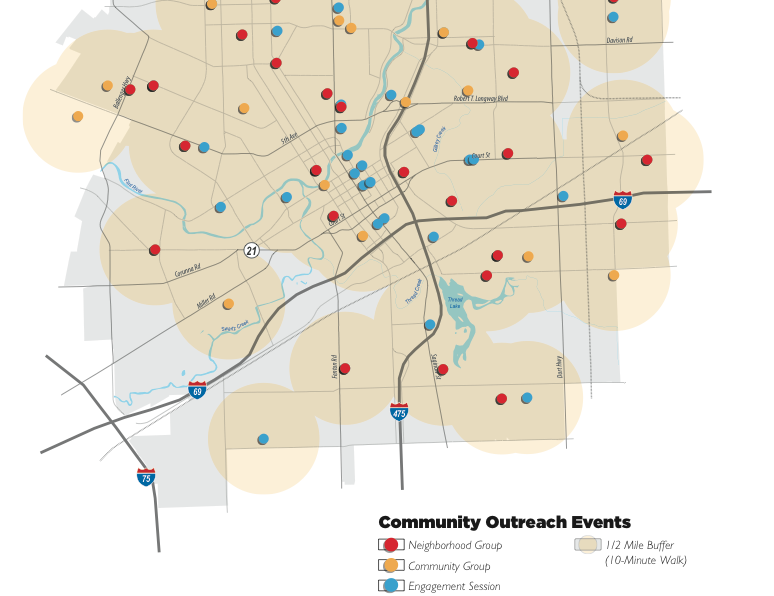

Since March 2012, the city has held 280 community meetings, some of which drew 500 people — a number that represents 0.5 percent of the city’s population — for a discussion of its future. The process was the first such public planning exercise for Flint, and one steeped in painful history. Hard feelings still linger over the construction of I-475, which destroyed an African-American neighborhood in the 1960s. For many residents, urban planning sounds too much like the top-down urban renewal strategies of that era. With a mix of support from the federal government and local entities, the city worked to address that by creating a document based on public input.

“How do we rebuild the relationship between residents and the city?” said associate planner Kevin Schronce. During planning meetings, “you had people from the North End of Flint, and the South End of Flint, and the more affluent areas, and you had to form a consensus at that table.”

Before the process started, Flint didn’t even have a planning department, so it used a $1.57 million Office of Sustainable Communities grant to hire a chief planner and two associates. Megan Hunter left a job with the city of Los Angeles to take a two-year contract with Flint. The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, which is based in Flint, gave another $529,477 to support the development and community engagement aspects of Flint’s master plan.

“Flint is already in the process of revitalizing,” said Alicia Kitsuse, a Flint area program officer for the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, which supports the Center for Community Progress. “The master plan is a reference for coordinating the resources in the city, and also pointing out the opportunities for raising the profile of assets and building on them… Engagement will be key to getting projects implemented.”

The Master Plan draws on planning concepts now being tried in other shrinking Rust Belt cities, such as Detroit and Youngstown. The city’s most depopulated areas have been designated Green Neighborhoods, where current residents will be allowed to remain in their homes, while new housing is prohibited. (A construction ban is hardly necessary — in 2012, Flint issued four permits for single-family houses.) The strategy, still untested, strives to balance the rights of homeowners who want to stay in depopulated areas with the public need to consolidate services and use fallow land more strategically.

Besides Green Neighborhoods, the plan calls for converting open space to state and county parks, and expanding existing parks around the Flint River and Thread Lake. This approach has been tried before in Flint: An abandoned Chevy plant, known as Chevy in the Hole, is being developed into public open space for art events and other activities.

One of the most significant elements of the Master Plan is its emphasis on mixed-use zoning and housing rehabilitation programs. In traditional residential areas, the city will encourage infill housing, rehabs and side-lot programs that transfer vacant lots to neighbors, so they can have suburban-sized yards. In large parts of the city, the plan proposes emulating the success of downtown Flint, where long-vacant hotels have been transformed into college dormitories and apartments whose vacancy rates hover between 0 and 1 percent. Flint has the highest rental rate in Michigan — 56 percent — and an older-than-average population, so demand for apartments and senior housing will likely be high. The plan calls for 5,000 new units downtown by 2040.

“Downtown Flint is the fastest-growing neighborhood in Genesee County,” Walling said. “We believe we can do something similar to that in a number of areas in Flint.”

Cities such as Detroit and Cleveland have successfully lured artists with cheap rents. Flint’s plan calls for low-cost loans to creative professionals who want to set up art-related businesses downtown. One key moment in downtown’s revitalization was the University of Michigan-Flint’s decision to become a residential campus. The plan will build on the city’s educational and research institutions with the establishment of a University Avenue Core, which will link Hurley Medical Center, Kettering University, and General Motors Tool and Die.

The biggest obstacle to attracting new residents may be the city’s murder rate, the highest in the nation. City leaders hope to reshape the urban environment to reduce crime by, for example, demolishing abandoned houses that are havens for drug dealers, and fostering an urban agriculture movement that could create new jobs. According to the document, “smart urban design, community partnerships, and city planning can also facilitate more ‘eyes on the street,’ thus reducing the likelihood of criminal activity.”

A new Master Plan won’t bring back everyone who left Flint in the last 50 years. But it may bring back some, and it will make Flint a more livable city for those who have stayed. After all, they wrote it.

Edward McClelland was born in Lansing, Mich. His book Nothin’ But Blue Skies: The Heyday, Hard Times and Hopes of America’s Industrial Heartland was released in May 2013 by Bloomsbury Press and was inspired by seeing the Fisher Body plant across the street from his old high school torn down. His book The Third Coast: Sailors, Strippers, Fishermen, Folksingers, Long-Haired Ojibway Painters and God-Save-the-Queen Monarchists of the Great Lakes won the 2008 Great Lakes Book Award in General Nonfiction. Like so many Michiganders of his generation, he now lives in Chicago.