In the last four years, more than 30 new businesses have opened on Broad Avenue in the Binghamton section of Memphis. After years of decline, the wide, storefront-lined avenue is finally rebounding as the spine of a new arts district.

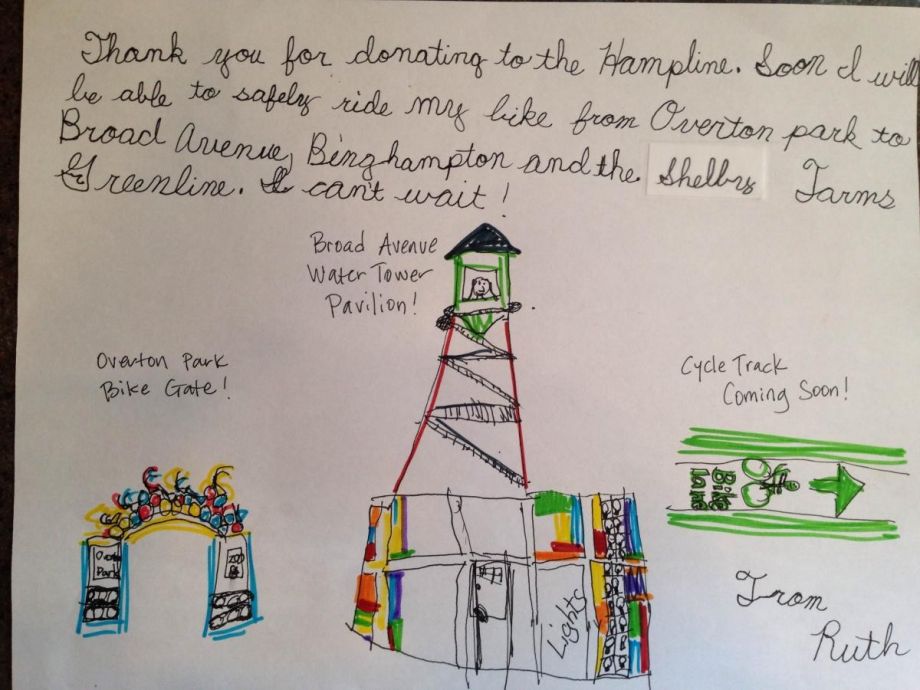

Ask locals what drove the change and invariably, they will mention the Hampline, a bike lane connecting Broad to some of the city’s most popular neighborhoods and amenities. The Hampline is being built largely with federal, state and city grants, but when a $75,000 budget hole cropped up in 2013, community leaders decided not to wait for more grant dollars from Washington and instead, turn to a new source of funding: the crowd.

The non-profit Broad Avenue Arts District and other local organizations came together to create a campaign on Ioby, a non-profit platform for fundraising for projects that do civic good.

Soon enough, they had raised the needed money and in the process, connected with hundreds of new Hampline supporters, bringing new attention to the project and to the changing identity of Broad Avenue. “I think the campaign helped Memphis understand what the Hampline was,” said Sarah Studdard, a spokesperson for the Broad Avenue Arts District.

The Hampline is one of a growing number of public space projects developed in part thanks to individual donors drawn in through an online crowdfunding campaign. When crowdfunding began to take off about five years ago with the 2009 launch of Kickstarter, the strategy was largely the province of artists and entrepreneurs looking for a way to raise quick capital for a creative project. With platforms like Ioby and Indiegogo, that is beginning to change.

In Chicago, the non-profit Windy City Hoops, which runs basketball programs in public parks and schools, recently raised $60,000 for a program it hopes will keep at-risk teens off the streets. In Philadelphia, a group raised $10,000 to cover a cost overrun on the city’s first major public skateboard park, $4.5 million Paine’s Park. Meanwhile, in Manhattan, a non-profit raised $100,000 for the Lowline, a sunlit underground park that, if fully funded, would run below the Lower East Side of Manhattan in a historic trolley terminal.

Public parks have always relied on support from donors but crowdfunding makes it possible for anyone to give at whatever level they can. “We had people who donated from $5 to $5,000, so it creates a lower buy-in point,” said Studdard.

At its best, crowdfunding can democratize the process of giving, a power that could mean big things for cities like Memphis where many neighborhoods have deep needs but shallow pockets.

Rodrigo Davies is a civic technologist and doctoral researcher at Stanford University who has been watching the evolution of crowdfunding closely. Last year, he published the first study of the use of crowdfunding for civic projects. One question he set out to answer was how crowdfunding could be a positive force in community development for communities at all income levels.

The study found that the people who launch campaigns tend to be younger adults who are supporting themselves but not yet obligated to families. They disproportionately live in dense urban areas. Would their projects aggravate existing disparities or be a help to communities with more financial pressures? “It’s clearly capable of doing both,” he said in a recent interview.

His research found that 81 percent of civic projects initiated on Kickstarter reached their goals, making these projects more likely to succeed than projects that don’t serve some kind of public purpose. One in five crowdfunding projects across all platforms included in the study explicitly reference benefits for underserved communities. He also found that while some platforms are actively reaching out to lower-income communities for projects, such as Ioby and Neighbor.ly, overall the majority of projects in the civic crowdfunding space are not coming from those communities.

When ioby crunched its own data last May, it found that 65 percent all projects were in low-income neighborhoods, and in some areas, like Memphis, the majority of projects were in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty where median household income is below $20,000.

In Davies’ next paper, he points both to a crowdfunding campaign to subsidize Google Fiber in lower-income parts of Kansas City, and to one in Oakland that paid for private security in an affluent neighborhood, giving residents there greater access to public safety than what other parts of town could afford.

Open space and parks are the most common civic project funded through crowdfunding. That comes as no surprise to Adrian Benepe, former New York City Parks Commissioner and a senior vice president at the Trust for Public Land. He sees any tool that can leverage private dollars for public parks as a net positive. Crowdfunding is a win-win, for him. “Rather than exacerbating inequality, private money enables a city to take public money and allocate it to neighborhoods that have no chance to do private fundraising,” he said.

Asked whether in his time in parks he saw large, multi-million-dollar projects sit unstarted for want of only thousands of dollars, he said it happens all the time. In New York City, he said, public agencies can’t proceed until all the money is in place. So in that way, private money can either get projects started or wrap them up, like with the Hampline or Paine’s Park. “It can be the last piece or the first piece,” Benepe said, but at a standard price of $1 million per acre for an active recreation park in most American cities, it’s unlikely to be the whole piece.

Crowdfunding may also be fostering new kinds of projects. For example, Ioby has eliminated a hurdle by sharing its non-profit status with unincorporated groups. It has only been providing fiscal sponsorship in limited areas up to now, but, as of last week, it’s extending it to any community group on Ioby in the U.S., making the campaigns’ gifts tax deductible.

There is social benefit in this cross-pollination of ideas and dollars across communities, Davies believes. “The received wisdom is that contacts between people tends to break down barriers,” he said.

For its part, Ioby says that about a third of the platform’s food projects are attempting to put vacant lots back to use as urban farms or food distribution sites. Looking forward, Ioby Executive Director Erin Barnes says that more green infrastructure and bike or pedestrian recreation projects are coming down the pike. Kansas City’s bike-share program, for instance, recently broke up its rollout into campaigns for different parts of town, an approach which also enabled its advocates to talk about disparities.

“You’re seeing a new slice of people appealed to with these projects,” said Davies, “who say, ‘There is something I can do to have an impact in my community, even if I can only donate 20 or 50 dollars.’”

Now that’s a proposition I’d throw a few bucks behind. How about you?

This article has been updated to state that while a majority of civic crowdfunding projects do not originate in low-income communities, a majority of projects initiated on the platform ioby.org are in low-income areas.

The column, In Public, is made possible with the support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.