It’s a cold, wintry-gray day on Ritner Street in the South Philadelphia. But turn a corner, past a deserted, brown park, and suddenly the street shines orange and gold. An imposing, carved fence presses against the sidewalk; statues of the Buddha spill onto the walkway. We are at Preah Buddha Rangsey Temple and the bright red gate is open.

A religious sanctuary for Philadelphia’s Khmer community, mostly comprised of Cambodian and South Vietnamese immigrants, it is also a communal locus, housing regular English classes and occasional colorful festivals. And if it looks like Preah Buddha Rangsey Temple is bursting at the seams, that’s because it is.

Muni Ratana, the temple’s head monk and CEO of the corresponding Khmer Buddhist Humanitarian Association, will sign a deal this month to buy 10 acres of land in Voorhees, N. J. to build a meditation center complex. Responding to community needs, the center will provide silence to meditate, parking spaces for thousands of devotees, and display traditional Cambodian architecture. It will be more accessible for some congregants who come from surrounding suburbs, though the South Philly stronghold will remain.

Across town, at 58th Street and Lindbergh Boulevard in the city’s southwest corner, beyond half-used warehouses with half-busted windows, another temple is taking shape. From the road it looks like a squatters’ compound. A boisterous pack of dogs announces visitors; a burn barrel smokes outside of a newly constructed house. But on the gate of Khmer Palelai Buddhist Monastery are clues of the nature of the community: Remnants of dilapidated prayer flags, and a sign in curly red script stating “No Alcohol No Weapons.”

The sign speaks to the incongruity of this location for such a spiritual landmark. On Lindbergh, dilapidated rowhomes are punctuated with gas stations and Chinese take-outs. The temple is tucked off the main road behind several garbage-strewn lots. But set away from the metropolitan hustle and bustle, the location is ideal for the monks: Spacious and quiet, with ample room for congregants driving from throughout the city and suburbs to park during festivals.

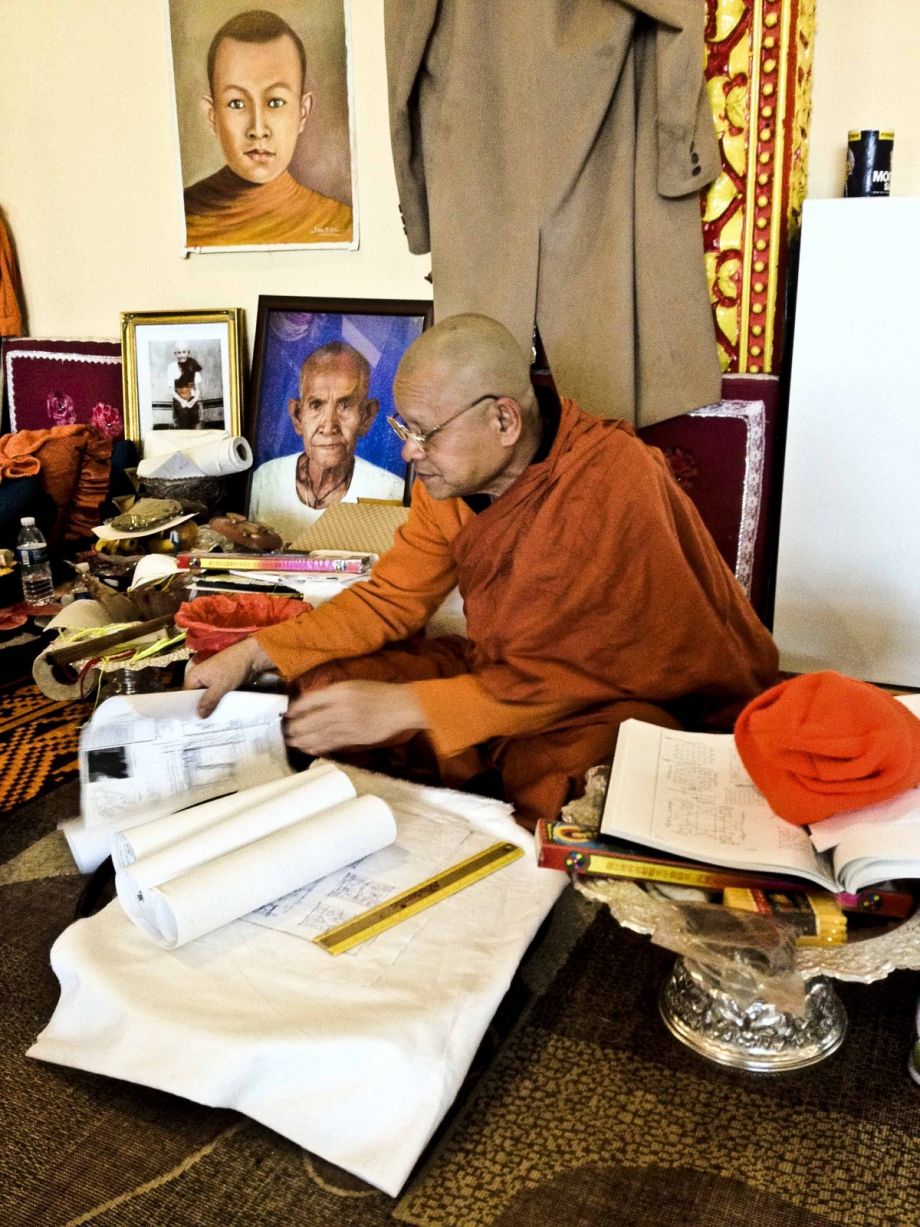

From outside, the sanctuary is visibly under construction, but inside it is warm and welcoming. Carpets cover the floor, Buddhas of many shapes and sizes bedeck the altar. Sitting on a red floor cushion, Sam Sokhoeun, the head monk, shows off countless blueprints and his dream board: A hand made poster covered in images of Cambodian monasteries titled “Buddhist Monastery Case Studies”.

Khmer Palelai monk Sam Sokhoeun shows the many plans that have gone into construction of the new temple.

One of the first Cambodian Buddhist temples in Philadelphia, Khmer Palelai opened its doors in 1986 in a converted Presbyterian church on Greenwich Street in South Philadelphia. The monks lived in the former Sunday school classroom. Their arrival in South Philadelphia was tense at the time, as the neighborhood began to shift from its historic Irish-American roots with the new influx of Asian immigrants. Cambodian Buddhists are now following the tradition of Jewish and Christian communities, anchoring their arrival around a central worship space and investing money and energy to revitalize affordable, run-down neighborhoods. Their expansion speaks to the financial growth and slow sprawl of the Cambodian community from their tight-knit loci in the city.

Accustomed to the Cambodian countryside, the monks were forced to squeeze into the tight dwellings of crowded South Philly. “In our country we have big land like this, with separate buildings for chanting and special events,” Sokeoeun said. “In Greenwich we had no choice, we had to make do.”

After more than a decade of crowding on Greenwich Street, the community bought the Southwest Philadelphia lot at the edge of the train tracks almost 10 years ago. Tied up in zoning and legal issues until 2011, they now have permission to build and have started work on the sanctuary, school and dormitory for the monks.

The physical expansion is a logical next step for a community that has grown over the last four decades. At last count, some 20,000 Cambodians live in and around Philadelphia, making it the fourth-largest such community in the country, according to the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia. In the city alone, there are four Khmer Buddhist temples, with chanting and services in the Khmer language. To see evidence of the community’s numbers, go no further than the 1100 block of Washington Avenue, where Cambodian and Vietnamese businesses dominate well-trafficked blocks

Most Cambodians came to Philadelphia in the 1980s and 1990s as refugees. Many vividly recall their experiences under the communist Khmer Rouge rule, when families were forced to flee their homes, camp in the jungle at the Thai border and languish in refugee camps. Rorng Song, executive director of the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia (CAGP), lived in a refugee camp for eight years before finally being accepted into the U.S.

When they first arrived, Song said, most of the refugees lived in cramped apartments, sharing rooms and working low-skilled jobs. “Anyone my age or older, we all experienced working in the farms in New Jersey in the summer, picking blueberries,” she said, and laughed at the incongruity of her story. She is a brisk, busy businesswoman now, dressed sharply in a blazer and gold embroidered scarf in her office in Olney. She works to connect Cambodians with social services and to promote and maintain Cambodian culture.

By the 2000s, she says more Cambodians owned homes and businesses, and the second generation started working professional jobs. Now that the community is established in work and home, they are spending ever more on their religious structures. “When it comes to religion our community is still very loyal and generous. We come from a war-torn country where religion was destroyed, temples were destroyed under the Khmer Rouge. When people were free… they felt reborn. They really believe in rebuilding the temple.”

The expansions are happening with little fanfare, and mostly funded by congregants. But the monks see a quiet flowering of Buddhism in the city. “Meditation is the teaching of the Buddha, but it’s not just for Buddhists, it’s for everyone,” Muni Ratana said, “I want the center in New Jersey to serve all of the people from Pennsylvania and New Jersey.”

Song of CAGP sees the Cambodian experience within the broader globalization of the city. “When this city was losing population, immigrants were replacing it… I’m proud of what Philadelphia has become. Now you can find any kind of food here, you can build friendships with many different people.”

Allyn Gaestel is currently a Philadelphia Fellow for Next City. Much of her work centers on human rights, inequality and gender. She has worked in Haiti, India, Nepal, Mali, Senegal, Democratic Republic of Congo and the Bahamas for outlets including the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Los Angeles Times, Reuters, CNN and Al Jazeera. She tweets @allyngaestel.