This analysis was published as part of The Bottom Line, my weekly newsletter reflecting on the challenges of addressing affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Subscribe to keep up with what I’m writing, thinking and reading every week.

Divestment doesn’t necessarily have a big, direct economic impact on the target of a divestment campaign, but history has shown divestment can be a powerful tool for galvanizing broader support around causes that might seem distant or foreign. Nobody likes to get caught with their hands in the cookie jar. But until someone digs into the numbers, all of our hands are in more cookie jars than we realize.

In Palm Beach County, Florida, the local government outright told county residents about one of the jars they were reaching into together: government bonds issued by the state of Israel. Back in March, Palm Beach County Clerk of the Circuit Court and Comptroller Joseph Abruzzo held a press conference announcing that the county government was the world’s largest investor in “Israel Bonds,” which made up $700 million of the Florida county’s $4.67 billion investment portfolio.

Not only that, but Palm Beach County had just made a new purchase of Israel bonds after county commissioners increased the cap on the percentage of its portfolio it could hold in Israel bonds, from 10% to 15%. The revelations drove a few concerned Palm Beach County residents to call for divestment. It’s not just Florida. The state of Ohio holds $262 million in Israel bonds.

Whether you’re on the side of investing or divesting from Israel government bonds, let’s use this moment to look at a pool of money that normally falls below the radar: state and local government investment portfolios.

College or university endowments typically get the most talked about during divestment campaigns. It’s often their students who are on the campaign frontlines, as they are today with calls for such endowments to divest from companies that do business with the state of Israel.

College or university endowments currently hold nearly $1 trillion of investments in their portfolios. Meanwhile, state and local governments across the U.S. hold more than $4 trillion in their collective investment portfolios.

How local government investments work

State and local governments’ investment dollars come from every household or business living, working or operating within their borders and therefore paying property taxes, income taxes, sales taxes or fees. Some of those dollars also come from the federal government grants and other income sources.

State and local government incomes and spending are never synchronized by default. Property taxes may come in only once or twice a year; sales taxes may come in monthly or quarterly. Payroll goes out at least twice a month; payments for construction and other work go out to contractors as projects hit key milestones. A bond issuance can mean millions come into a city’s coffers within a few hours but are spent over several years as work is completed on a big infrastructure project.

Between coming in and going out, those dollars could all be sitting in state or local government bank accounts, earning a relatively modest rate of interest. But many cities choose to invest the bulk of their revenue as it comes in, hoping to earn a bit of investment return along the way, later selling off investments as they need the cash.

And what investments are in those portfolios?

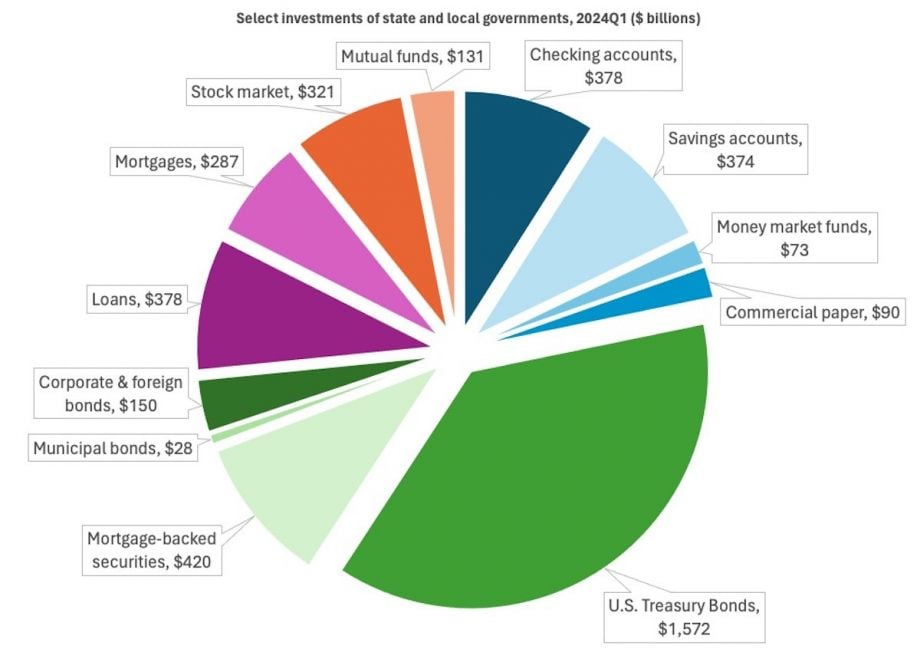

This chart covers almost all of the more than $4 trillion that state and local governments have in their investment portfolios, based on data compiled by the Federal Reserve. (It’s important to note this total excludes state and local government pensions, which are a whole other bucket of money with a different purpose and decision-making structure. Public pensions are typically overseen by a board of trustees that sets its investment policy, which determines what each pension’s version of the pie chart above looks like.)

State and local government investment policies are typically set by the state or local legislative body — like the Palm Beach County Commission, which tweaked its investment policy to allow the office of the County Clerk of the Circuit Court and Comptroller to purchase additional Israel bonds.

In the pie chart above, Israel bonds fall under “corporate and foreign bonds.” But at the same time, there could also be corporations doing business with Israel that are part of the stock market investments in a state or local government’s investment portfolio. Some of those company stocks or bonds could also be part of the mix of investments held as part of a mutual fund. Some of the banks where a state or local government holds its checking, savings or money market accounts could also be providing loans or serving as the investment banks that underwrite Israel bonds.

How divestment is possible

As I wrote in this newsletter a few weeks ago, “divesting from death” can be complicated, but it’s not impossible. The complications arise from the fact that as “institutional investors,” state and local governments typically don’t themselves select what’s in their investment portfolios. Instead, they contract out those decisions to private asset management firms who handle slices of those portfolios.

The challenge is finding asset management firms who are able and willing to work with investors whose interests may go beyond the mere financial.

Asset management firms typically need to get through an approval process determined by the state or local legislators before being eligible to manage public dollars for investment. A divestment campaign that covers all bases has to include examining the criteria used in that selection process.

Asset management firms often specialize in one slice or several related slices of the pie. “Fixed income” is a kind of catch-all term that includes everything from U.S. Treasury bonds to mortgage-backed securities to municipal bonds and corporate or foreign bonds. Some firms specialize in stock market investments. Sometimes one company can have different teams internally working on different slices of the pie. A county might hold its checking accounts at JPMorgan Chase while a whole different arm of the same company manages the county’s fixed-income investments.

It’s important to note that the contracts for asset management firms do typically fall within the specific areas also known as “asset classes”: fixed income, “equities” for the stock market, sometimes “alternative” for private equity or venture capital funds, sometimes there’s also a real estate slice. Banking contracts may be reviewed on an annual basis, or every other year. Other contracts may get reviewed less frequently. The City of Chicago reviews its asset management firm relationships every year across all its asset classes and banking relationships.

The highest priority for the treasurer, comptroller or chief financial officer is to safeguard public dollars from potential losses. That’s why the largest slice by far in the pie above is for U.S. Treasury Bonds, generally considered the safest investments in the world. But there’s still room for some intentionality, starting with the criteria used in the selection process. Back in 2019, for example, I wrote about how the St. Louis City Treasurer’s office started requiring banks seeking authorization to hold city deposits to submit documentation showing how they were involved in responding to the Ferguson Commission Report, forged out of the uprisings following the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown.

In between selection periods, the office administering the state or local government investment portfolio also has some discretion. Each time there is a big influx of cash, say a semi-annual property tax payment deadline, their office begins calling approved asset managers to allocate cash for investment.

That can be a moment, for example, when the office can be strategic about who it calls first. Maybe the call list can always start with the minority- or women-owned asset management firms; private foundations have used this strategy to help move more of their portfolios under the management of minority- and women-led asset management firms over the past few years. Maybe asset management firms doing business with Israel or financing the fossil fuel industry can be at the bottom of the call list, if they’re on the list at all.

How to see where your local government is investing

Most state or local governments won’t come out with a press conference to announce investments in Israel. So how can researchers and activists find their own state or local government’s investment portfolio?

Start by looking for its “comprehensive annual financial report,” or some combination of those words. These reports have to be formatted to certain global accounting standards and published annually for state and local governments to maintain a good credit rating. They are typically quite long and complicated, covering multiple entities for which the state or local government is financially responsible.

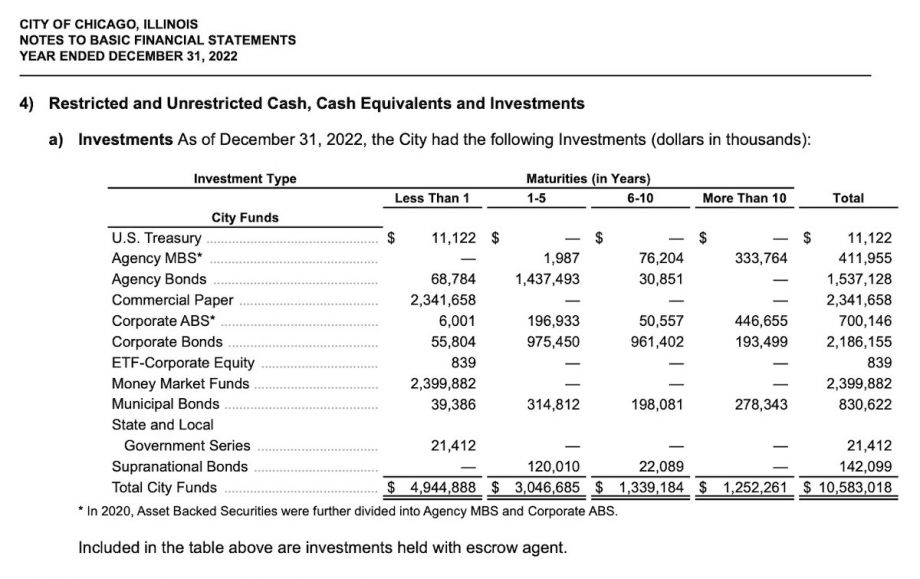

Ultimately what you’re looking for is a table like this one, which comes from Chicago’s most recently available annual comprehensive financial report:

I can’t emphasize enough that this chart is just a starting point. In this example, which isn’t too out of the ordinary, the city’s bank accounts are missing from the table above. A few pages down, there’s another note stating the city has around $307 million deposited across all its various bank accounts, in addition to the $10.6 billion investment portfolio above.

The next step if you’re curious would be to see which firms are managing those dollars. For that, the Chicago City Treasurer’s office conveniently provides lists of both the asset management firms handling the portfolio above as well as a list of banks authorized to hold municipal bank accounts — though it does not provide the dollar amounts that each firm or bank manages or holds on behalf of the city.

From there, I’d start looking into which asset management firms match up to the asset classes where there are investments I want to discourage, then see if those firms have any clear ties to those kinds of investments. For example, Bank of America is an authorized depository for the City of Chicago, and it is also one of the global banks that underwrite the most recently issued round of Israel bonds, according to the Israeli business publication Globes.

While it is possible to be an authorized depository for a city without actually holding any deposits from that city, that’s one place to start looking around to see where there might be undesirable connections.

State and local government dollars are some of the most representative pools of dollars invested on behalf of the public in some way. More than university dollars, which are supposed to benefit universities and their students. More than foundation dollars, which are tied to specific foundation missions and the unique history of each foundation. Meanwhile, all of our money is linked to these $4 trillion-plus investments, by virtue of paying state or local sales taxes and property taxes (even renters, assuming landlords pass those costs onto tenants).

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)

Add to the Discussion

Next City sustaining members can comment on our stories. Keep the discussion going! Join our community of engaged members by donating today.

Already a sustaining member? Login here.