One last great play may be in store for the Houston Astrodome.

Obituaries for “the eighth wonder of the world” were written in November 2013 when voters rejected a $217 million bond initiative that would have transformed the historic sports arena into a special events venue. The former home of the Houston Oilers and Astros hasn’t hosted sports teams since 1999, or any event since 2009. With the prospect of demolition casting a long shadow, urban planners faced an all-too-familiar problem: How do you repurpose an aging stadium of gigantic proportions?

If the Urban Land Institute has anything to say about it, you do it by combining a preservationist ethic with uniquely Houston needs. ULI’s new proposal to redevelop the iconic stadium as a “grand civic space” is the Astrodome’s best bet for a useful — even beautiful — future.

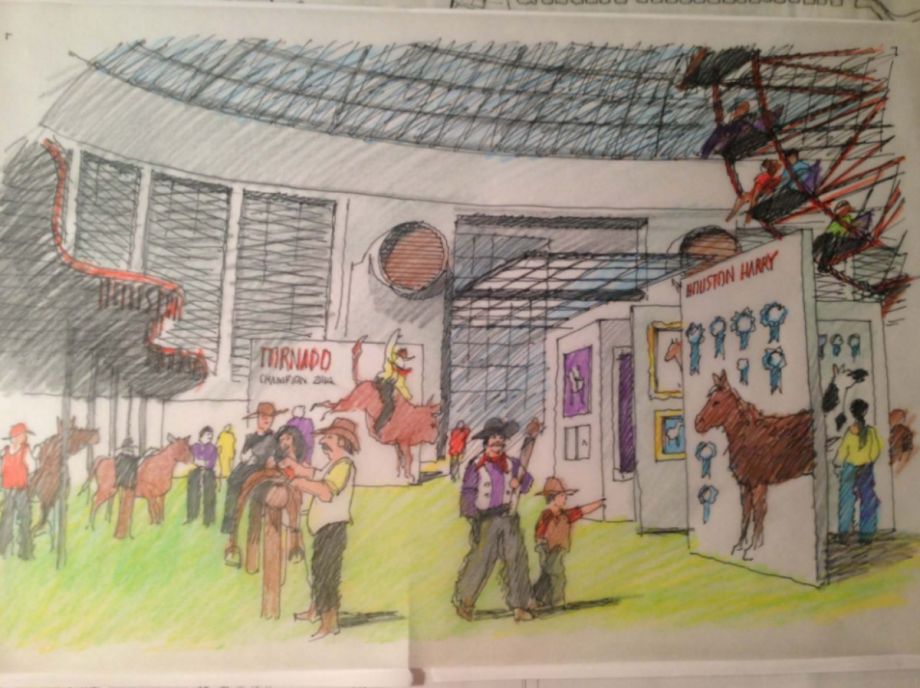

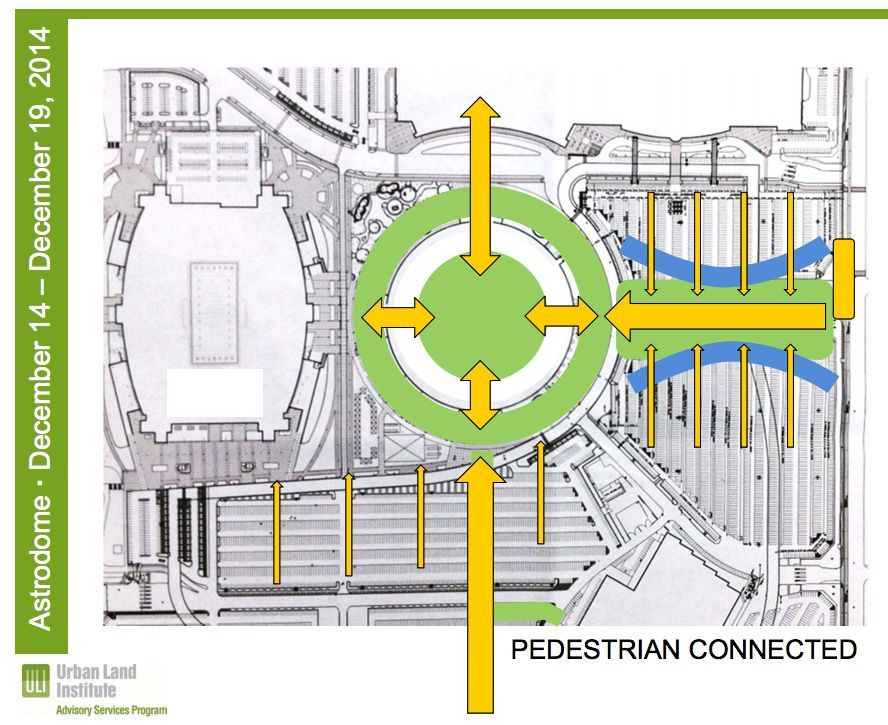

Here’s the vision: Leverage the “can-do” spirit of Texas to transform the 18-story stadium into a one-of-a-kind civic park, rich with green space, gardens, pavilions, zip lines, climbing walls, and trails for biking and running. An oak-lined outdoor promenade and greenery would circle the publicly accessible building, and space would be designated for exhibitions and festivals. Part of the arena would showcase Houston history, including its legacy of space innovation. A natatorium, library and skate park round out the key component of the redevelopment. The Astrodome would also connect with the nearby NRG Center and NRG Stadium so that visitors could enjoy the dome before walking over to rodeos, conventions or football games. (See ULI’s full proposal here.)

(Credit: Urban Land Institute)

While fashioning a modern “adventure park” in an old facility presents technical challenges, it’s not unprecedented. In Detroit, the Globe Building, built in 1892 as a riverfront manufacturing hub, re-opened as the Outdoor Adventure Center, operated by the state’s Department of National Resources. In Pittsburgh, an 80,000-square-foot building that once housed a metal fabrication company, was transformed into The Wheel Mill, an indoor bike park.

But the real brilliance of the ULI proposal — and the reason it beats out earlier notions to turn the stadium into a museum, or water park, or demolish it altogether — is that it fits perfectly into the city’s greening momentum.

Houston is going big on sustainability and green space. The Bayou Greenways project is a $480 million public-private project that is radically changing the relationship between city residents and the bayous. It will add 150 miles of parks and trails in the city limits by 2020. Houston also signed on as a “Complete Streets” community, meaning that this car-centric town is becoming walkable. The city is also investing in public transit and a rapidly expanding bike-sharing program. And Houston, which opened an office of sustainability in City Hall a few years ago, is incentivizing the greening of office buildings. All this points to real excitement for a greener and more physically active Houston among city leaders, planners, business owners and citizens. Turning the Astrodome into a wonderful new city park fits right in.

(Credit: Urban Land Institute)

“We live in Katy, but we could come if there was (an indoor park in the Astrodome) … and even be willing to pay for use of facilities,” Jessie Cheek, a mother of five, wrote in an August email to the Houston Chronicle. “More greenery is very needed.”

What’s more, the indoor park model works well for Houston, which struggles with suffocating summer heat. The need to find shelter in hot weather is why Houston patched together a network of climate-controlled tunnels over the 20th century, spanning 95 blocks and 77 major buildings. While Houston has embraced Discovery Green, a beautiful new outdoor park, an indoor park in the Astrodome would provide the city with another public-spirited recreation option that offers a climate-controlled alternative.

(Credit: Urban Land Institute)

But the success of ULI’s proposal depends on its ability to make the practical business case for the project — to tell the “why we all win” story in economic terms. As I wrote in “The Lone Star Progressive,” a Next City profile of Houston Mayor Annise Parker, brass-tacks urbanism is what works in this city. Sentiment is not enough. Reformers must make the practical case for their progressive vision — to speak not the language of ideals, but the language of utilitarianism.

Neither ULI nor its Harris County partners have put a price tag on redevelopment, nor have they clarified whether voters will be asked to support it. They’ve only said that the project will be backed by both the private and public sector, as well as local hotel tax revenues, historic tax credits, and possibly TIRZ (Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone) money and county funding.

(Credit: Urban Land Institute)

Once developed, planners estimate annual operating costs as being between $500,000 and $1 million per acre used. Event space, they said, could generate revenue to pay for itself: movie nights, food and beverage services, charity events, a farmers’ market, and more.

All this sounds good. But we need more precise redevelopment numbers in the complete report that is expected from ULI in about two months. No hedging. Transparency about the business case for this project will make all the difference in its viability.

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in Elle Magazine, the New York Times, Politico, the Columbia Journalism Review, Next City and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book. She has been a Fulbright fellow in Nairobi, Kenya and a Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of THE POISONED CITY: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books in 2018.

Follow Anna .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)