Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Photo by Steve Grant

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberBill Zawiski is Ohio’s water quality man and he knows the most efficient way to clean the infamously dirty Cuyahoga River that flows through Cleveland and other Ohio cities. It’s not a new regulation or cutting-edge infrastructure. The answer: tearing down old infrastructure — specifically, dams.

“If you are looking at the most economical way to gain watershed restoration, dam removal on its own jumps ahead of many things on the list,” says Zawiski, water quality supervisor with the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency.

Zawiski explains the science simply. Dams prevent waterways from cleaning themselves. When they are removed, the natural filtering process can work its magic.

“When the dams are removed, you are allowing that river to be free flowing, removing the chemicals the dam retains, and letting the river function in a natural way,” he says.

For about five years now, the Ohio EPA official has been working with local, state and federal agencies to move forward with an ambitious plan to tear down a 55-foot dam known locally as the Gorge Dam and clean up polluted sediment festering in its wake. The stately concrete waterfall was built in the early 1900s as a place to generate electricity, a purpose it ceased to serve in 1991 when nearby industry stopped relying on it for power. Aside from serving as a landmark in Gorge Metro Park, about 4 miles outside Akron, the dam serves no practical function. This is true of many of the 2 million to 2.5 million U.S. dams the EPA estimates are out there. However, they can impair water quality. Buried in the lake behind Gorge Dam are 832,000 cubic yards of sediment laced with arsenic, mercury and other harmful hydrocarbons that will have to be removed and then buried in a landfill.

John Waldman is a professor of biology at Queens College in New York. In 2015, he wrote an influential paper arguing that “no other action can bring ecological integrity back to rivers as effectively as dam removals.”

The paper got attention because it reinforced an idea gaining credence in many parts of the United States, particularly in urban regions where clean water and public waterfronts are both in short supply.

Since 1912, about 1,300 dams have been removed in the U.S. But in the last 10 years, the pace of de-damming has sped up considerably with nearly half of the removals happening since 2006.

“We have entered into a new era of dam removal because a broad array of people — ranchers, Native Americans, irrigators, businesses and communities — are realizing opening up and restoring rivers is an effective way to save taxpayer money, revitalize communities and help the environment,” says Michael Scott, acting environment program director at the Hewlett Foundation. To mark its 50th anniversary last year, the foundation is awarding $50 million in grants to fund community efforts to remove obsolete dams and restore rivers on the West Coast.

But $50 million is a drop in the rushing water where dam removals are concerned. Especially at a time like now, when federal support for the EPA and its environmental cleanup projects are being threatened. President Donald Trump has floated cutting the agency’s annual budget by nearly a third, to $5.7 billion. Though Trump’s proposal is just a starting point for budget negotiations with Congress and it’s possible that some EPA programs will be spared, there is no doubt that dam removal projects could be imperiled.

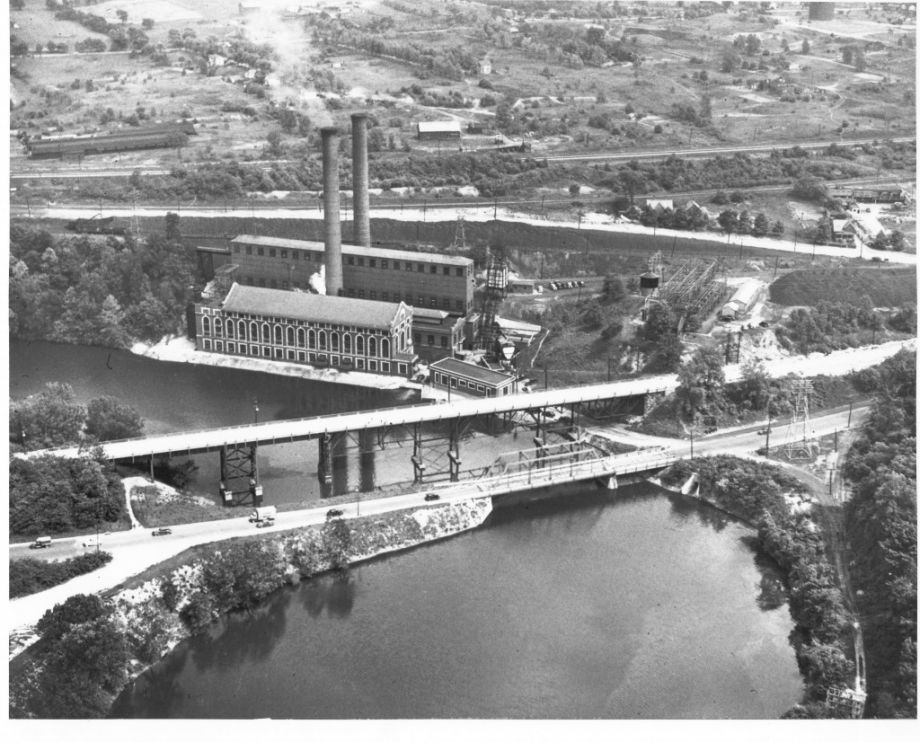

The Gorge Power Station, sometime before 1945 (Credit: Cuyahoga Falls Historical Society)

For Gorge Dam alone, the cost of removal and cleaning up left-behind sediment is estimated to be $70 million. The Ohio EPA is banking on the federal government to help cover some of that; the federal government is now working with the state agency on a preliminary design that will cost $1.4 million, $750,000 of which is coming from the state. A spokeswoman for the Ohio EPA says there is “no commitment” as of now for further assistance from Washington, but Cuyahoga Falls Mayor Don Walters has said that plans are in the works to lobby congressional and state representatives to sign letters of support for the project.

“A lot of these dams are unsafe and don’t serve any purpose anymore,” says Martin Doyle, director of the water policy program at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment. “They represent making electricity and grinding grains and floating logs in a different era. There is certainly not many reasons to keep these dams, given that removing them lets the river oxygenate and clean itself up. But the big question is that even though there are not strong reasons to keep these dams, does that equate to spending tons of money to remove them in cities across the country?”

It’s a question that is being asked by local governments and the people they serve in dozens of communities, from Cleveland to Milwaukee to Colchester, Connecticut, and Washington State.

The American Society of Civil Engineers classifies almost a fifth of U.S. urban dams — 14,000 of 84,000 — as “high-hazard,” meaning there will be loss of life and significant economic loss downstream if they fail. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates it would cost $21 billion to fix these dangerous, aging dams. Meanwhile, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers projects that it would take $2 billion just to fix 20 of its most decrepit dams falling apart. Some of these aging dams are hydroelectric energy generators, some have flood control aspects to them, and some merely send water flowing into recreational lakes.

“I was at a recent meeting of the National League of Cities, and almost everyone there was talking about sprinkling their cities with some environmental green stuff, some solar panel on roofs, new sidewalks, better storm water infrastructure,” says Jane Goodman, city council president in South Euclid, Ohio, and executive director of Cuyahoga River Restoration. “All that is good, but cities need to realize that one of the most important environmental projects they can be working on these days is restoring the city’s most important piece of infrastructure, which is often the river running through their cities. I love what we are doing on the Cuyahoga, because it has taken a lot of time and planning, and it mirrors the issue so many cities now face, which is to make the water that runs through their city cleaner and safer, and not harmful to the people that live there.”

The Cuyahoga River in Ohio is relatively small in the world of rivers. It begins in the countryside in Northeast Ohio and runs into Lake Erie in Cleveland, and is only about 85 miles long from beginning to end, nowhere near the size and cultural import of the Mississippi and Colorado and Rio Grande rivers in the United States. But while the Cuyahoga hasn’t loomed as large in the nation’s history books, its story is representative of many American waterways.

For a few hundred years, the Cuyahoga powered local industries while serving as their wastebasket. While factories hummed and new cities rose up nearby, the river became more and more polluted. Since the 1970s, Northeast Ohio has spent nearly $2 billion cleaning up the Cuyahoga River.

In some respects, this little Ohio river in the industrial heartland became the symbol of what was right and wrong with how American businesses used and abused water resources in the U.S. A fire on the Cuyahoga River in downtown Cleveland in 1969 captured the attention of local and national media, and inspired many Americans to think differently about the future of their waterways. That 1969 blaze — the 13th time the Cuyahoga had caught fire in a big way since 1868 — was the one that engaged politicians and early environmental activists to form the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

The Cuyahoga River formed about 12,000 years ago when the glaciers retreated northward. Cuyahoga Falls, situated at a turn in the river, became a popular park destination in the late 1800s. Pictures from the era show suited men and formal-hatted women strolling near the three-tiered, 22-foot-high cascading falls.

But once the dam was built there, the falls no longer had a communal purpose. And while the river has become cleaner in the decades since the fire, some sections of it do not meet EPA clean water standards — and Gorge Dam is one reason why.

An aerial view of the plant at Cuyahoga Falls taken prior to 1945 (Credit: Cuyahoga Falls Historical Society)

“It is real simple in some respects,” says Jennifer Grieser, who helps manage water resources for Cleveland Metroparks and is chair of the Cuyahoga River Area of Concern Advisory Committee. “I don’t know if you will visually be able to see a difference in the whole river when that dam is removed, but it will make a big difference in the river system functioning better.”

The goal is to have the Gorge Dam removed by 2019 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the famous 1969 fire. “The Cuyahoga River is a microcosm of what was great and not so great with this country over the years,” says Goodman. “We will be proud when we get this dam out of the river and we move closer to having it cleaned up well.”

The project is historic in another way: There is no partisan bickering about its value.

“With the new administration coming in, there is a certain air of uncertainty regarding the funding of environmental projects, but from the beginning this dam removal has had the backing of both parties in the state,” says John Kaminski, president of Friends of the Crooked River. “It became very simple for those of us who live here: We could clean up the river and create about 40 acres of park around the river by getting rid of an old dam from another era. Pretty simple.”

Despite bipartisan interest in these projects, paying for them can be complicated. Often, the tab is covered through a mix of federal and state grants coming from different agencies and private money from businesses associated with the dam or region and philanthropy.

Then there are the indirect costs associated with removing dams. In Columbus, Ohio, for instance, there are two dams that local authorities would like to remove but doing so would open a veritable mess of expenses. The dams carry sanitary sewer pipes through them and across the rivers and the cost to replace those sewer lines would be $44 million.

“In a perfect world, we’d love to take all of the dams out,” says George Zonders, spokesman for Columbus’ utilities department. “But we’d have to build new infrastructure sewer lines and adding in pump stations and the cost would be passed on to our citizens in higher drinking water charges and we can’t do that.”

But that same city of Columbus has found success with two dam removal projects completed since 2010. By removing two dams — one near Ohio State University and one downtown — the city was able to restore nine miles of river for public use and create a new 33-acre greenway.

Science is on the side of advocates for dam removal but as recent history has made clear, facts aren’t always what motivates communities to act. In many towns, the local dam is a beloved landmark. Some remember their first kiss as teenagers being by its falls, others remember it as the spot where their father taught them to fish or the place where the family would go to cut ice out of the river during the winter. “Those are the hardest arguments to deal with, the hardest things you have to overcome in convincing people that lives will be better off if the dam is removed,” says Frank Magilligan, a geography professor at Dartmouth College.

“Cities need to realize that one of the most important environmental projects they can be working on these days is restoring the city’s most important piece of infrastructure, which is often the river running through their cities.”

“The big question, and there are many, is that there are many reasons to take out a dam, but being for or against it depends on who you talk to,” he says. “The problem is finding an intersection between the influence of those at the top in government or foundations, and the … people who live near the river and have dealt with the dam their whole lives.”

But even if communities do come together around dam removal, it is an open question whether or not the EPA will be able to help them get the job done. An agency budget cut is almost a certainty, and water projects such as the San Francisco Bay Program, and Great Lakes and Chesapeake Bay cleanup programs are all on the proposed hit list to trim the spending by 25 percent.

How those cuts will affect dam projects is difficult to gauge. For example, local authorities in Ohio had anticipated $45 million in federal support from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI). In December, Congress approved $300 million per year for it, but proposed EPA cuts list the GLRI funding getting dropped by 97 percent, from $300 million down to $10 million annually.

“We are certainly concerned about what appears to be an attack on science, quite honestly,” says Amy Kober, spokeswoman for American Rivers, a nonprofit group that works on many water cleanup projects involving rivers. “If any grants that fund clean water river restoration are stopped, not only rivers will suffer, but local communities will suffer, because public health and public safety and local economies rely on healthy rivers.”

Kate Dempsey is the state director for the Nature Conservancy in Maine. She hopes that the dam removal trend can outlive the current political moment. “We saw that when we removed the dams from the Penobscot River, people living in the area developed a pride in where they lived, they celebrated the different ways fish moved as part of the natural state, and they wanted to come down to the river instead of ignoring it,” Dempsey says.

Dempsey says it’s too soon to know how the EPA will fare, but that the nation must remember the Cuyahoga River and the fire that rose out of it in 1969, inspiring the Clean Water Act.

“But free-flowing and cleaner rivers are now possible,” she says, “and that, we have to build on.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been corrected to note that there have been two dam removal projects in Columbus, Ohio. A correction has also been made to reflect that Trump has proposed cutting the budget of the EPA by $2.6 billion.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine