Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

A Zero Waste proponent at New York City's Earth Day 2017.

Photo courtesy NYC Department of Transportation

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberAcross the country, city waste programs are coming off a 2018 to forget. Recycling programs have been in financial straits after the market for recovered paper and plastic fell out when China cut imports in 2018. India, Malaysia and other countries then followed suit. Some cities have suspended recycling programs altogether; still others started incinerating recyclables, which has damaging environmental consequences. The issue becomes more urgent now that a number of cities are running out (or have already run out) of landfill space. The disposal alternatives include spending millions to transport garbage to landfills hundreds of miles away.

It’s a far cry from the mood earlier in the decade, when a number of U.S. cities boldly declared their intention to get to “zero waste,” meaning they intended to keep 100 percent of all trash out of landfills and divert it to other uses. Intentions certainly have been laudable: municipalities such as New York, San Francisco, San Diego, Austin and now Boston have announced plans to cut down on the trash they produce while stepping up recycling and composting programs. Each has declared its intention to boost sustainability, decrease their city’s greenhouse gas emissions and (eventually) send no more garbage to landfills, or in some cases waste-to-energy plants or incinerators. Yet every city in this brave group has collided with formidable obstacles and come up short.

San Francisco, arguably sustainable waste disposal’s shining city on a hill, began its quest in 2002. By 2012, year nine of its zero-waste plan, the city boasted an impressive 80 percent diversion rate, meaning four-fifths of the city’s garbage was being recycled, composted or otherwise reused. Yet in late 2018, just two years before San Francisco’s target date, the city announced it wouldn’t reach the finish line on schedule.

Nearly 3,000 miles away, New York City unveiled in 2015 a well-publicized zero-waste goal of 2030. Since then, inertia has struck on several fronts. By 2018, the city’s diversion rate was stuck at around 20 percent, considerably below the 35 percent national average cited by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Austin began its zero-waste quest in 2012 with a diversion rate of 38 percent. The goal was to hit an interim target of 50 percent by 2015, but at that point the city had progressed only to 42 percent. San Diego, another 2040 zero-waste aspirant, is doing better at 66 percent, but still has a long road ahead.

While urban zero-waste goals seem very much alike, each city grapples with unique shortcomings. In San Francisco, despite progress in the zero-waste effort, you might say its successes finally hit the wall — one made of plastic, electronic devices, and other materials that just can’t be recycled. Recology, the private waste collector San Francisco contracted for both garbage and recycling, has spent $33 million over the last three years to boost the local recycling rate in order to help nudge the city closer to its lofty goal.

As New York City’s municipal budget surplus dwindles, less money is earmarked for projects that form the base of its zero-waste push, including expansion of residential organic waste pickups around town. Austin is contending with a jackrabbit population growth rate of 34 percent for the decade that ended in 2017, a figure that exceeds the nation’s other 50 largest metropolitan areas, according to its chamber of commerce. More people means more garbage, and Austin will have to sprint to keep up.

Newcomers to the zero-waste bandwagon don’t have it any easier. Boston announced a zero-waste program in 2018, and will reveal specifics soon. Not long afterward, the city faced sticker shock when shopping around its recycling contract (a key prong in its plans). Only one bid came in at a whopping $6 million per year, potentially a $3 million increase. That doesn’t bode well in a city whose 25 percent recycling rate already falls behind national averages.

Given current market conditions and obstacles, are urban zero waste programs a pipe dream, or a feel-good financial sinkhole? Surprisingly, upside exists amid the high costs, obstacles and start-stop progress. Both the private and public sides of civic waste disposal are getting a better sense of how to forge ahead. Three opportunities stand out as places where cities can effectively make the most progress toward zero-waste goals: creating a commodified demand for waste materials; separating valuable substances out of city collections with greater efficiency, namely organic waste; and decreasing the overall amounts of trash generated by residential and commercial customers.

In this week’s feature and next, Next City takes a constructive look at ideas that can help zero-waste cities move closer to their goals, and further the quest to cut waste, spend less, and become more sustainable global habitats. In this story, we look at where zero-waste efforts stand in key cities, and the ways that Austin in particular has commodified recycled material in the marketplace. In next Monday’s part two, we examine burgeoning composting programs that divert organic waste, and enforcement solutions such as pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) that aim to decrease the volume of waste cities generate.

All zero-waste programs, whether newly minted or nearing their second decade, have faced rollout pains. Start with agreement on the basic definition of what “zero” means. Various waste industry factions have disagreed as to whether the label means complete sustainability, or a target that falls just shy of that mark.

Neil Seldman of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance says in the last few years, zero-waste advocates have come to grips with reality over idealism. “Absolute zero waste is an aspirational goal,” he says. “Proponents are professional people and want to show that we’re not reaching for pie-in-the-sky or something that’s impossible, so we’ve tempered that with realism.” What does that mean in practice? Seldman says a 90 percent diversion rate is probably the best that can be reached; about 10 percent of the garbage cities produce is unsalvageable, and destined for landfill.

“The days of cheap disposal are over, and environmental justice issues will make incineration unviable as an alternative.”

There’s also disagreement over which tools cities have at their disposal fit within a zero-waste framework. The more stringent proponents insist that burning garbage in waste-to-energy facilities or incinerators runs afoul of the movement’s dual credo of simultaneously shrinking disposal and minimizing the release of greenhouse gases. If one of the guiding objectives is cut back on piling trash in landfills in order to lower the amount of methane released in the atmosphere, then setting flames to the garbage and releasing carbon dioxide in the process nullifies those benefits.

No matter how they parse the zero-waste label, cities are scrambling for trash solutions. The reasons why San Francisco, New York, Austin and other municipalities hired consultants, pored through disposal options and hammered out thick policy statements stem from problems that are uniform from coast to coast.

For starters, a growing number of cities feel the financial pinch, paying more to dispose of their trash or to find the space to dump it. New York foots an ever-larger bill to ship garbage off to distant landfills in Upstate New York, Virginia or South Carolina. The expense has ballooned to a projected $412 million in the preliminary city budget for 2020, compared to just under $370 million in 2016.

In some regions, disposal options closer to home such as landfill or incineration have dwindled, particularly in the Northeast. In 1980, Massachusetts had 300 landfills. Today, that number is less than five. But disposal problems are not limited to the Northeast. Both San Diego and Austin have local landfills that will soon have no additional capacity.

The nation’s 76 waste-to-energy incinerators are another possibility, but most of those facilities were built between the 1970s and 1990s, so relying on that aging infrastructure is not a long-term solution. Incineration comes with additional expenses, including hauling garbage to the fires and then transporting ash byproduct away from facilities.

To make matters worse, many incinerators were built near disadvantaged urban neighborhoods, and have come under fire for the hazards they may cause. “The days of cheap disposal are over, and environmental justice issues will make incineration unviable as an alternative,” says Amy Perlmutter, a consultant who has worked on recommendations to Boston’s zero-waste initiative.

Communities across the U.S. have realized that the future of waste disposal depends in large part on generating sufficient demand to balance the supply of trash zero-waste programs take out of the waste stream. “The key to success is going to be cities that incorporate an approach that includes recycling and composting, but [one that is] also based on economic development,” says Amy Perlmutter, the former head of San Francisco’s recycling effort who has been working as a consultant advising Boston’s zero-waste startup.

Cities such as Austin have significant incentive to keep their sights locked on zero-waste. A study the city sponsored in 2015 found that local reuse and recycling had sparked some $720 million of economic activity, with a potential as great at $1 billion. On top of that, the study found that 80 percent of what the city threw away could have been recycled or composted. What compounds the problem is that garbage sent to city landfill is piling up, with no plans in place to open additional landfill capacity.

At [Re]verse Pitch 2019, Dean Young of HID Global shows a sample of the waste product being donated for the competition: polycarbonate skeletons, 900 to 1,400 pounds of which his company produces each week. (Screenshot courtesy City of Austin)

Austin’s zero-waste plan was released in 2011, a 321-page document two years in the making. The voluminous plan maps out Austin’s ambitious steps to channel 90 percent of its trash away from landfills and incinerators by 2040. The city didn’t shy away from aggressive interim goals, either. A 50 percent diversion rate goal was set for 2015, and 75 percent by 2020. Austin’s starting point was 38 percent in 2010. The city’s 2016 waste analysis showed that diversion had increased to 42 percent, a higher number that was nevertheless under target.

Updated figures won’t appear until 2020, when the city commissions a new in-depth disposal analysis. There’s reason for optimism. For one, since commercial waste makes up 85 percent of the city’s total, efforts to address that part of the problem could yield a potentially outsized payoff.

The city of Austin prides itself, in the words of city spokesperson Mimi Cardenas, on being “the blueberry in a bowl of tomato soup.” Partisan political references aside, Austin can point to some innovative ideas the city has supported to generate a market for recyclables and other materials that easily can be extracted from its waste stream. As a result, the city is arguably at the forefront of efforts to create or jumpstart markets to buy, trade and consume materials that otherwise would end up in the garbage.

One such experiment seems like a science fair crossed with a yard sale — a showcase where business models are based on inventions made entirely out of waste scraps and other bric-a-brac. Another idea can be characterized as Craigslist with a twist. Both have caught on locally, with potential for expansion beyond Austin metro limits.

Austin launched one experiment, the [Re]verse Pitch Competition, four years ago, part of the legion of ideas spurred on by the Zero Waste Plan. The contest attracts entrants who are local artists, engineers and other creative types and sparks a fair amount of buzz in South and Central Texas. The competition’s challenge is to devise a business plan that makes something marketable out of heaps of trash that nearby companies and nonprofits are eager to donate to the cause. In past years, starter donations have included expired canned goods from a food pantry, damaged pressboard furniture, distillery dregs, and even a mound of used mesh delivery bags.

The [Re]verse Pitch Competition is upfront about its environmental responsibility and do-good intentions, but make no mistake: It’s strictly capitalism that moves contestants the most. Here, one entity’s trash is a startup’s potential treasure trove. Winners bag as much as $10,000 in seed capital, along with a mound of raw material for immediate use, not to mention a fair amount of notoriety. “There’s a lot of energy in the room, a lot of networking going on,” says Natalie Betts, the head of Austin’s recycling programs. “It’s fun and exciting, and part of the appeal is that this blends startup ideas with sustainability and environmental solutions. Half the people in the room are there to take part as competitors, mentors or advisors to contestants, and the other half are there because they find the competition to be interesting.”

This year, the first leg of [Re]verse Pitch began on February 26, attracting roughly 150 artistic and science-leaning entrepreneurs. It kicked off with supply and sustainability officers for local companies taking turns at the podium to narrate powerpoint slideshows displaying a wide variety of castasides while a lively audience chattered in the background. A local winery was on hand to hawk the estimated 10 to 15 tons of white and red grape skins, stems and seeds that will be left over after the 2019 vintage has been pressed. An ID card manufacturer offered up 5,800 pounds of polycarbonate shells — cutout leftovers that look like squared-off plastic swiss cheese from a children’s game. A local cancer clinic pledged 100 or so styrofoam coolers and reusable freezer packs.

After contestants get the briefing on what scraps, debris and dross are available, the race is on. In the following weeks, participants summon their muses and devise the process alchemy and business plan they’ll need to convert on their vision. The city of Austin pitches in by offering entrepreneur workshops and a legion of mentors for guidance that come from a roster of local entrepreneurs, financiers and engineers. The hand-holding helps many contestants reach the finish line and submit a plan that includes designs, logistics and even some preliminary financials. On April 30, the contest draws to a close, culminating in a ceremony where a panel of five judges selects winners.

A gloved hand scoops through what looks like sawdust, but which is really hundreds of thousands of juicy grubs, fattened up by restaurant food waste to become chicken and pig feed, courtesy of 2016 [Re]verse Pitch winner Robert Oliver and his company, Grubtubs. (Screenshot courtesy Grubtubs, via Vimeo)

Another contest similar to Austin’s competition will be held in New York City for the first time this year. The NYC Curb to Market Challenge is the creation of Montana private equity venture capitalist Chris Graff. The event will offer a first-prize kitty of $500,000 to the best idea and business plan centered on reuse of some portion of the Big Apple’s garbage. Its perks are similar to Austin’s, including consulting and connections to advisors and angel investors as well.

Past [Re]verse Pitch champions have invented straight-up wonders of recycling and composting. Take Grubtubs Inc., a company that sprang to life from a first-place show in [Re]verse Pitch 2016. Founder Robert Oliver’s brainstorm was to convert food scraps from Austin restaurants into feed for pigs and chickens.

To collect food waste while blocking foul odors, the Grubtubs team designed special air-tight, 6.5-gallon plastic tubs that can be stowed unobtrusively in a restaurant’s prep and dishwashing areas to collect food scraps in “back of the house.” Once full, containers are transported to local chicken and pig farmers, where phase two kicks in.

It’s then that Grubtubs adds its secret ingredient — a liberal helping of black soldier fly larvae. The bugs are known for their ravenous hunger and make short work of the waste food within the tubs. Once the scraps have been eaten, the farmers feed the grubs to chickens and pigs, who devour the protein-rich food. It doesn’t hurt that Grubtubs charges farmers less than what they pay for commercial feed. Finally, when the grubs are gone, Oliver’s company circles back, retrieves the buckets, washes and sanitizes them, and returns the tubs anew to participating restaurants.

The idea has worked so well, the company is thinking big. A new ordinance in Austin requires 6,000 city restaurants to adopt responsible food-waste solutions. In an interview, Oliver said one of the biggest challenges will be scaling demand on the restaurant end of the business. Grubtubs has set its sights on signing up 1,000 restaurants for supply and 12 local family farms as end subscribers, an operation that it estimates will feed 36,000 chickens and keep 9 million pounds of trash out of landfills. Next will come recruiting farmers — particularly those who produce organic meat — to sign on. After that, Oliver thinks their business model will be primed to roll out coast to coast.

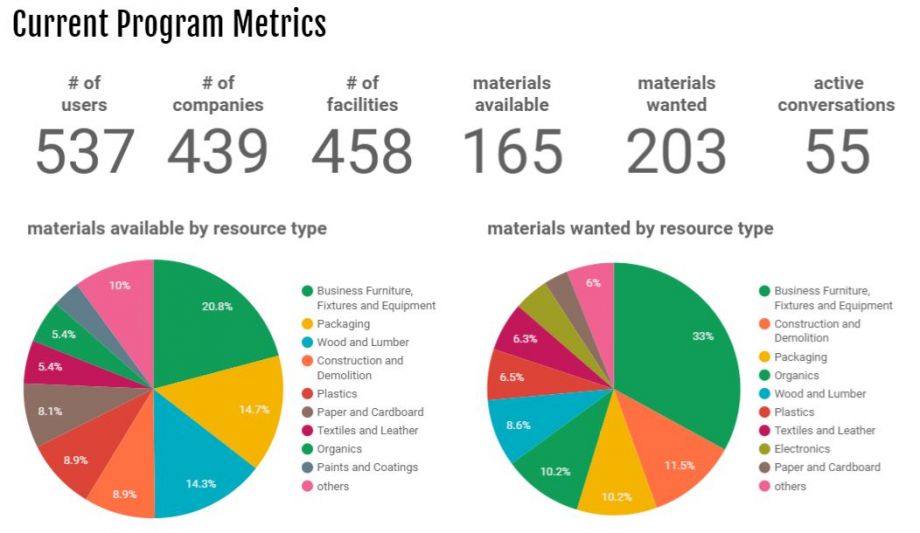

Another success is the Austin Materials Marketplace, an online exchange similar to Craigslist. Companies set up accounts to buy, sell or give away lumber, plastic, textiles, or construction and demolition remnants. In essence, one party offers what they’d normally pile into dumpsters — bulk leftovers, used furniture, manufacturing afterproducts and more. Another party steps up to haul the stuff away for their own end use.

Since it began in 2014, the marketplace has developed relationships with more than 500 users and close to 450 companies. By the city’s tabulation, the exchange has brokered 622 unique transactions, with a gross value of more than $630,000 — and that’s before any reuse or repurposing of the exchanged materials. In all, the city estimates the exchange has kept 1 million pounds of refuse out of landfill. According to Betts, although some offers have a price attached, most transactions are giveaways, provided the recipients pick up and haul away their spoils. In this model, suppliers get rid of garbage and lower their trash bills in the process. Recipients score raw materials or inputs that they can transform into sellable products.

(Graphic courtesy Austin Materials Marketplace)

The underlying idea isn’t new. A number of industry groups have set up waste-swapping sites of varying magnitudes; for example, New York City started a program called Wastematch. What sets the Austin Materials Marketplace apart is the city’s commitment to the project. The city government spent roughly $175,000 during years one and two to get the exchange off the ground, an annual cost that has since dropped to the mid-$80,000 range. The city pays for hosting, software and associated internet fees but also for time their staff spends actively sleuthing for deals and connecting buyers and sellers with potential matches. Betts says the city is contemplating ways to make the service more self-sustaining. A participation or subscription fee won’t work because it may price out nonprofits, schools and small businesses who benefit from low-cost materials acquisition. Consultations with a local business council, meanwhile, have centered on instituting a transaction fee based on the value of goods changing hands.

Perlmutter says several factors will determine how economically viable waste-matching or recyclable markets can be. Just how much state governments contribute is one mitigating factor. State intervention can boost the scale and scope of fledgling markets for recyclables. The secret lies in aggregating demand. Local markets are smaller, have fewer participants and may have a narrower list of materials in demand. To expand recyclable exchanges statewide would draw in more potential buyers and sellers.

“One of the challenges is broadening what we use and how we use it,” she says. “When we talk about the available materials, we tend to think just of of recycling bottles, cans, paper and plastic.” The problem, adds Perlmutter, is that those trade in international commodities markets and go through up and down cycles. Success also depends not only on repurposing a wider variety of materials, but also creating a greater array of products out of them. “This isn’t just about creating newsprint out of recycled paper, but instead thinking more broadly and expanding markets to new products such as artisan paper or handmade paper,” she says.

In the early 2000’s, Perlmutter headed a group that aimed to spur that sort of activity. Called the Chelsea Center for Recycling and Economic Development, it was a joint effort between the University of Massachusetts and the state environmental affairs office in Boston. The center functioned as a sort of reuse chamber of commerce for the state of Massachusetts. In some cases, it sponsored studies to look at helping communities spark businesses to reuse local streams of plastic and paper.

Other projects promoted new uses of existing waste materials. For example, the center helped one Massachusetts company work up a business plan to develop a variety of plastic lumber, test it and roll out a product offering. One marketing study dove into reusable toothbrush handles and the best way a local manufacturer could drum up business, while a third investigated making wheel chucks for commercial trucks out of reused plastic.

The [Re]verse-pitch meet and materials marketplace are both part of broader efforts Austin has tried in pursuit of zero-waste’s missing link: A viable marketplace. Compost and recycling programs pile additional costs on top of city waste disposal budgets. Creating bonafide demand for plastic, paper, glass, food waste and other materials removed completely out of Austin’s garbage would not only give those programs a financial boost, it would transform zero-waste programs from budgetary burdens to possible economic boons.

There’s every reason to think that is possible and perhaps closer in reach than many cities realize, argues ILSR’s Seldman. In a recent Next City story, Seldman argued that thanks to recycling, the U.S. has potentially the most valuable trash on earth, a raw material that under the right conditions could become a revenue stream for municipalities. “It’s a question of cities seizing control, claiming and capturing those materials in order to create wealth, jobs, and tax base while reducing the costs of waste management,” he asserts. “A stable market for recyclables will make that happen by giving cities a sense that they are in control, [as opposed to] the big waste management corporations or China.”

James A. Anderson is an English professor at the Lehman College (Bronx) campus of the City University of New York.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine