After 112 years, golf is making its Olympic comeback. But while the official Rio 2016 website gushes about “a new chapter in the history of Brazilian golf about to be written,” in the meantime the golf course the city is building for the event is doing serious damage to Rio de Janeiro.

Gil Hanse, the American architect who won the bid to design the Olympic course, has called it “the opportunity of a lifetime,” saying, “I don’t know that we will ever get to build a more significant golf course.”

Significant, without a doubt, but not because of any misty-eyed Olympic symbolism. Rather, the course’s importance stems from its environmental and legal implications. On its way to becoming reality, the project has handily steamrolled all potential roadblocks, from land-use regulations to environmental protection laws to legislative checks-and-balances.

Its first casualty is the municipal budget. The City of Rio has committed R$60 million ($26.8 million USD) to the course, currently under construction in Barra da Tijuca. The median cost for design and construction of an 18-hole golf course is around $4.5 million. Anything above $5 million is considered “high end,” according to Sports Illustrated contributor John Garrity.

If construction of the course was an essential component of Rio’s Olympic dreams, its exorbitant cost might be less problematic. But this isn’t even the case. Itanhangá Golf Club, one of Rio’s two existing 18-hole courses, ranks on Golf Digest’s list of the 100 best golf courses outside the U.S. Just a 20-minute drive from the Olympic Village, Itanhangá would have met IOC regulations, according to the club’s president, Alberto Fajerman.

But “Itanhangá was never sought out…about the possibility of hosting,” wrote Fajerman in a letter to the city council. “Itanhangá Golf Club does indeed have the conditions to meet the structural demands of hosting the golf competition.” When asked, International Golf Federation (IDF) President Peter Dawson insisted that while “there are other courses in Rio, there is no Plan B at present because I don’t think we’ll need one.”

To complicate matters further, the new course’s chosen location in Barra da Tijuca is laughably ill-suited. Over the past 30 years, Barra da Tijuca has experienced explosive development, sprouting so many high-rises and shopping malls that it’s been dubbed “Rio’s Miami Beach.” The chosen site for the Olympic golf course turned out to be some of the region’s last undeveloped real estate, resting on 11 million square feet of ecologically fragile marshland.

Until the bulldozers arrived, the area was a patchwork of mangroves, sandbanks and shoals jutting into the Marapendi lagoon. The whole area is made up of the Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Forest) biome, a sliver of terrain that used to encompass an area nearly twice the size of Texas. Though less than one-tenth of Brazil’s Mata Atlântica remains intact, these remaining fragments still contain the highest biodiversity index of any biome on earth, harboring eight percent of the world’s species, many of which are found only in Brazil. The region surrounding the Marapendi lagoon — which is protected at the federal, state, and municipal levels — contains around 300 identified species, including endangered animals like the yellow-necked alligator, the beach lizard and the crested guan.

“The environmental questions are obvious,” says Jorge Borges, an urban planning specialist who works for the city council. He adds that, though not as immediately apparent, the more serious issue is that the project is “completely overrun with legal issues.”

Thanks to Brazil’s 1988 constitution — “a masterpiece,” according to Professor Fernando Walcacer, former city prosecutor for urbanism and the environment — there’s no shortage of tough environmental laws on the books. The 2006 Atlantic Forest Law declares the entire biome a national patrimony and mandates its protection against further degradation. The national forest code also sets down a list of “environmental crimes” punishable by federal law.

Additionally, most of the golf course site lies inside an Area of Environmental Protection (APA), subject to strict sustainable-use guidelines. The remaining portion of the parcel was part of the public Marapendi Municipal Reserve, an area under “permanent protection,” which theoretically makes it untouchable.

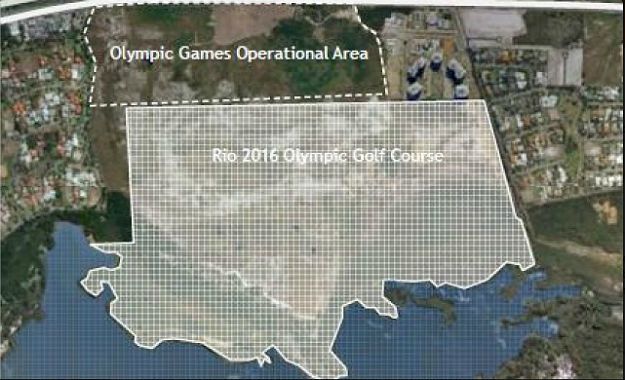

A map of the area to be developed.

Trouble is: “There is a very great opposition between what the laws say and the practice here in Brazil in the area of environmental protection,” says Walcacer. “The real estate and contracting industries have always been economically powerful [in Rio]. They are very important when it comes to financing political campaigns.”

According to Marcello Mello, a biodiversity gestation specialist, “Political authorities and business interests in Rio de Janeiro have been uniting to cash in on development in the city’s last green spaces.” With October elections fast approaching, many authorities have much to gain by approving the licensing for development projects no matter what.

In order to gain access to the golf course land parcel, the city council passed Complementary Law 125 in late December 2012, during an emergency session just before its holiday recess. First, it declares that the construction of a golf course inside the Marapendi APA met the sustainable land-use guidelines, even though those guidelines limit development within APAs to “ecological-economic zoning… protecting the biological diversity and ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources.”

Second, the law redraws the borders of the Marapendi Municipal Reserve, carving out the piece that lays within the intended golf course’s bounds, thereby nullifying its protected status. So much for public land under “permanent protection.”

Finally, in exchange for funding the course’s construction, developer RJZ Cyrela is now allowed to construct 23 new 22-story luxury high-rises on the parcel. This tramples previous zoning regulations that capped construction to six-story buildings and residences. Cyrela, which did not respond to a request for comment, is poised to cash in on some of Rio’s most valorized real estate.

Apartment suites in the neighboring Riserva Uno condos, also owned by Cyrela, start at over R$6 million (nearly $2.8 million USD). By virtue of their location, the new crop of high-rises will be worth even more: R$16 million ($7 million USD). According to Andréa Redondo, an architect and former president of the City Secretary of the Preservation of Cultural Patrimony, “The [government’s] discourse is very seductive, but the project is just a real estate tool at its core.”

The passage of Complementary Law 125 throws up a number of red flags. Despite the area’s protected status and the clear presence of endangered species, no environmental impact studies were carried out and no resource management plan was formulated, both in violation of the law. There were no public audiences to its passage, as is expressly required by law. In response, the city’s Public Defenders have called for the suspension of work on the course. “The World Cup and the Olympics gave the city government the pretext for completely diminishing good urban planning in the city of Rio de Janeiro,” Walcacer laments. “We are going pay dearly for this.”

Because of critical delays, it remains to be seen whether or not Olympic medals will end up gracing the necks of the world’s best golfers come 2016. R&A chief executive Peter Dawson has confirmed that a test event on the Olympic golf course is on, but failed to clarify what that event will be or when it will be played. According to the draft version of the Olympic test events, recently released by Rio 2016, golf’s test event is scheduled for August 15, 2015. This would just squeeze though the IOC’s one-year cut-off between the test and the real thing.

When asked if the necessary work on the course would be completed in time for the Olympics, IGF Vice-President Ty Vokaw dodged the question, saying only: “Well, predictions are dangerous things.” No matter what happens, though, the project’s illegalities and environmental consequences are unacceptable.

So far, nothing — not an official complaint by two city council members, not a class-action lawsuit, not environmentalists’ outrage — has managed to halt the golf course’s construction. According to Borges, “Impunity is our national reality. And this project is very good business.”

UPDATE: Rio’s public defenders (Ministero Público) now have a shot at canceling the environmental license for the course, with the aim of halting construction and requiring the recuperation of any environmental damage in the area. After being stalled for several months in the hands of the assigned public defender Ana Paula Petra, on August 14, 2014, the public defenders filed another lawsuit against the city of Rio and Fiori Empreendimentos. Construction on the golf course has now reached 59 percent completion.

_on_a_Sunday_600_350_80_s_c1.jpeg)