Amid rising college costs, America’s rebounding economy continues to favor those with a four-year diploma. For workers with a bachelor’s degree, average weekly earnings are nearly 50 percent higher — and unemployment is roughly half — when compared to people with no more than a high-school education.

And although college enrollment spiked during the Great Recession, more than two-thirds of all American adults don’t have a college degree. Where do you work without a bachelor’s and in what field? Those are just a couple of the questions investigated in a new report titled “Identifying Opportunity Occupations in the Nation’s Largest Metropolitan Economies,” released last week by the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia, Atlanta and Cleveland.

An “opportunity occupation,” according to the authors, is one that is both accessible to someone without a bachelor’s degree and pays the median national wage (adjusted for local cost of living). “We identified jobs in healthcare, professional office settings, tech supervisory positions, along with some of the trades,” says Keith Wardrip, a researcher at the Philadelphia Fed who also co-authored a companion study that investigated the same questions, only zoomed in on his Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Delaware region.

“Both reports drive home the point that place matters, place really affects the type of work that someone has access to,” Wardrip says.

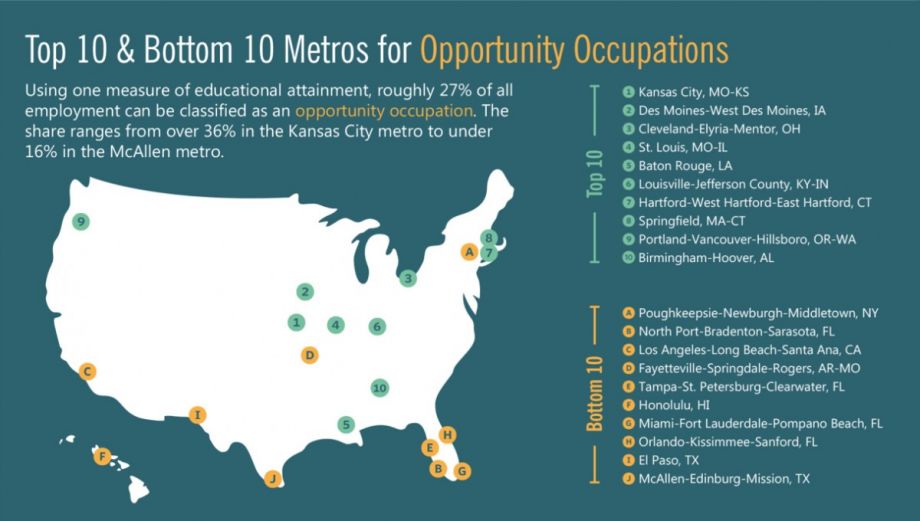

Overall, between 20 and 27.5 percent of all jobs in the nation’s 100 largest metros were estimated to be opportunity occupations — with significant regional variability. In the highly educated economy of Washington, D.C., for example, only 13 percent of jobs were opportunity occupations. (That’s based on the share of online job advertisements that ask for a minimum education equal to or greater than a bachelor’s degree — one of three measures of accessibility that the study analyzed.) In St. Louis and Kansas City, among the highest-ranking metros, 30 percent of employment is accessible to people without a bachelor’s degree.

The Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia, Atlanta and Cleveland released this chart last week with a report called “Identifying Opportunity Occupations in the Nation’s Largest Metropolitan Economies.”

“We do see that wage inequality is lower in metropolitan areas where the opportunity occupation share is higher,” Wardrip says. While that might seem intuitive — less inequality exists in metros that offer more mid-range wages — the correlation of other trends are not so obvious.

Look at nursing, which the study identified as the profession with far and away the most opportunity occupations. Between 2011 and 2014, online job ads in the profession that did not mention a bachelor’s degree decreased by a huge amount during that period, nearly 10 percent. And that’s at a time when there’s a shortage of registered nurses — and the profession is in the midst of a projected 20 percent growth period between 2012 and 2022. Why is there increasing demand for nurses, and yet, a simultaneous increase in the barrier to employment? Part of the answer has to do with recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine, which wants the share of nurses with a bachelor’s degree or better to increase from 50 to 80 percent by 2020 — in order to match the growing array of competencies required on the job, in areas like research, policy and public health.

All of that’s to say it’s difficult to pinpoint the profession-specific reasons for shifting shares of opportunity occupations. Employers aren’t necessarily changing their preferences willy-nilly; they’re often responding to larger forces at work, such as new prerequisites across an industry. But the basics of supply and demand still allow for some variation on the local level, which explains why nursing job ads requesting less than a bachelor’s degree increased 8 percent in Madison, Wisconsin, between 2011 and 2014 — bucking the national trend — while they decreased in the vast majority of metros studied.

The Federal Reserve Banks’ analysis of changes in online job ads does have at least one positive takeaway for those without a college diploma: Out of 23 occupations studied, 17 showed a decrease in ads calling for workers with four-year degrees — meaning, most of the largest opportunity occupations have become easier to access over the last five years. “It’s interesting that we’re seeing small relaxations in the education that’s required,” says Stuart Andreason, co-author of the study and a researcher at the Atlanta Fed. “I think it might mean that the labor market is rebounding.”

The authors also don’t discount the positive impact that the growing industry of workforce development and “sectoral training partnerships” has made in terms of providing pathways for non-degree holders to enter workforces like healthcare and tech. One such example is Tech Impact, a nonprofit based in Philadelphia that trains young workers without college degrees over the course of a 16-week information technology program. Participants, who are mostly African-Americans living in the city, earn industry-recognized certificates like Cisco IT Essentials and CompTIA A+ certifications, which can lead directly to positions as help desk techs — one of the 15 most prevalent opportunity occupations, according to the new report.

“Our data show that our graduates are earning three times more than what they did when they came in, generally speaking, in the range of $35,000 to $40,000 a year,” says Executive Director Patrick Callahan.

More research needs to be done, in order to parse out which workforce-training programs are most successful and why certain metros are faring better than others in terms of opportunity occupations. “Really this first report it descriptive in nature, gives us the landscape,” says Wardrip. “The next report we want to do will help answer the whys.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Malcolm was a Next City 2015 equitable cities fellow, and is a contributing writer for the Fuller Project for International Reporting, a nonprofit journalism outlet that reports on issues affecting women. He’s also a contributing writer to POLITICO magazine, Philadelphia magazine, WHYY and other publications. He reports primarily on criminal injustice, urban solution and politics from his home city of Philadelphia.