In a 1938 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Boston, a mosaic of color-coded sections warned lenders away from neighborhoods purportedly risky for investing and highlighted other areas as “safe,” prime for investment.

Formulated for 239 U.S. cities in the 1930s, HOLC’s make-or-break ratings could doom whole neighborhoods to neglect and eventual blight, and they were based heavily — and openly — on racial composition. Area description forms that accompanied the maps noted the percentage of foreign-born and black residents and flagged “negro infiltration” as a major risk factor.

White neighborhoods and suburbs typically were graded A, their favorability symbolized by green shading. Predominantly black neighborhoods and those with even a few black households received D grades, making it nearly impossible for homebuyers to get loans insured by the new Federal Housing Administration. These low-rated areas were colored red, leading to “redlining” as a shorthand for the system’s detrimental and isolating effect.

Lacking access to mortgages, people in redlined communities were vulnerable to predatory lending or “contract buying,” in which one missed payment could cause a family to lose a house and all the money they’d invested in it. Blacks who could afford to buy were barred from higher-rated neighborhoods by discrimination, sometimes in the form of restrictive covenants that kept whites from selling to blacks even if they wished to.

In his 2014 case for reparations for descendants of enslaved African Americans, Ta-Nehisi Coates implicates redlining, which dramatically constricted blacks’ options for homeownership, a crucial source of wealth-building.

“Redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived,” Coates writes.

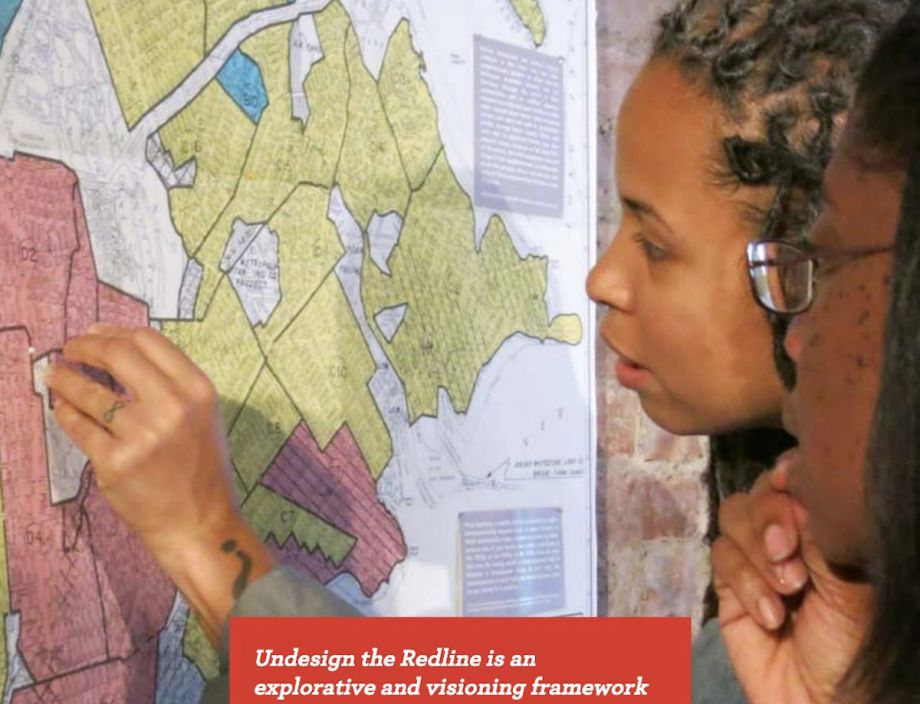

Now, redlining’s history, its persistent impact over generations, and some possible paths toward change are the focus of “Undesign the Redline,” an interactive exhibit created by New York-based Designing the WE. A version of the exhibit with Boston-specific elements is now on view at The Brewery, a small-business complex in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood. Its panels line four walls of a lobby just outside the office of City Life/Vida Urbana, a grassroots housing justice organization.

The Brewery itself lies in a previously redlined neighborhood now grappling with displacement of longstanding residents of color as it shifts to a hot market for affluent newcomers. This trend has been studied and mapped by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Other once-redlined, now-desired Boston neighborhoods include the South End, already among the city’s most expensive areas, and Roxbury, a majority-black neighborhood now seeing housing costs soar as developers have scooped up devalued properties to create luxury housing.

In many other U.S. cities redline-era patterns of racial segregation persist and areas once shaded in red still suffer neglect, poverty and even “planned shrinkage.”

City Life/Vida Urbana, which works with residents fighting sharp rent hikes, eviction and foreclosure, is organizing a series of exhibit tours led by locals whose lives or communities have been affected by redlining’s long shadow.

“One of the goals of bringing the exhibit here is to have it serve as an ‘each one teach one’ approach,” says communications coordinator Helen Matthews, “where no one is holding the knowledge and explaining it from on high, but it’s more of a horizontal platform.”

The exhibit ran earlier this year at Boston Architectural College and at Boston City Hall. With the move to Jamaica Plain, Matthews says, it will have reached three intended audiences: future urban designers, policymakers and people “on the front lines of displacement.” All of these groups may be unused to seeing housing instability as a systemic issue rather than an individual failing.

“Each individual story of displacement today is a microcosm of a long arc of discriminatory housing policy,” Matthews says.

Leading one of the first tours in mid-September, Roxbury resident Lawrence E.J. Carty tells of his great-grandparents who moved to Detroit from Georgia in the Great Migration of the early 20th century. Threatened in the South, they sought the greater physical safety of the city’s closer neighbors, he says, though they left behind 700-plus acres of land inherited from a formerly enslaved ancestor. They were able to settle and prosper in Conant Gardens, a thriving black neighborhood that suffered less from redlining than other parts of Detroit.

“So what I’m trying to bring to this is, there were these systemic forces at play, but sometimes people were able to overcome them,” he says. “Conant Gardens was born despite the prevailing economic and political forces.”

The exhibition begins with a “What is redlining?” intro and proceeds to tell the story through maps and documents that prove redlining’s racial element, along with ephemera like restrictive covenants and insurance underwriting manuals that reinforce the notion that white-only areas “invaded” by “incompatible” racial or social groups inevitably would lose value.

The practice of redlining technically ended in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act, but its ramifications persist.

One white tour attendee mentions a first-time homebuyer event in Roxbury that drew some 1,000 participants, only a tiny handful of them white. She draws a connection between historic redlining with lower home and business ownership today.

“The young African American couples, their families have no history of ownership,” she says. “And now with the new industry of marijuana shops, white people can open them with money from their families, because they weren’t affected by all this.”

Boston today bears the infamous distinction of an enormous racial wealth gap. A 2015 Federal Reserve Bank of Boston report showed the median wealth of Boston’s white households at $247,500 and that of black households at just $8.

The exhibit’s timeline traces systemic racism through slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, white flight, capital flight, the war on drugs, mass incarceration and today’s “serial displacement.” A parallel timeline shows grassroots fights against oppression and discrimination, including Boston successes like the halting of a planned I-95 extension that would have cut through Roxbury and Jamaica Plain and an anti-displacement movement that created the Villa Victoria affordable apartments in the South End.

The exhibit and tour are meant to be interactive, and this tour sparks myriad discussions, jumping from school segregation to the GI Bill’s disparate benefit to neighborhood-erasing urban renewal projects.

For Joel Mackall, a Roxbury resident who leads black history tours in Boston’s North End, a key takeaway was redlining’s double-sided impact.

“Not only was it an obstacle-making system — a designed ‘cage’ for black folks — the design of it was to improve opportunities for white folks,” he observes. “That’s important. If you’re talking about redlining, you should always include ‘greenlining,’ too.”

The final panel of “Undesign the Redline” — which this one-hour tour, with its robust conversational detours, doesn’t quite reach — encourages viewers to consider positive alternatives. It highlights case studies such as a community land trust initiative that united two groups not traditionally aligned.

The exhibit, co-presented by City Life/Vida Urbana, Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corporation, Designing the WE and Enterprise Community Partners, runs through Dec. 31, 2019.

And after that? Several participants suggested bringing the exhibit to other Boston neighborhoods. Dante Comparetto, a community activist and school committee member in Worcester, Massachusetts, expressed hopes of bringing the exhibit to Worcester and ensuring that high school students see it.

“Worcester has a similar story to Boston’s,” he says, “and if we can tell those stories, it can really improve civic engagement. Knowing the history of your place can really be empowering.”

This article is part of “For Whom, By Whom,” a series of articles about how creative placemaking can expand opportunities for low-income people living in disinvested communities. This series is generously underwritten by the Kresge Foundation.

Sandra Larson is a Boston-based freelance writer covering urban issues and policy. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times, Guardian Cities and the Bay State Banner. See her work at sandralarsononline.com.

Follow Sandra .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)