Sock Yong Phang is a professor of economics at Singapore Management University, and every month, when she gets her paycheck, 20 percent of her income is automatically diverted to a savings account managed by the Singaporean government. Like all Singapore workers, her contribution is required by law. So is an additional 17 percent contribution from her employer. The savings account, called the Central Provident Fund, is meant to help Singaporeans pay for healthcare, retirement, and housing. When workers like Phang want to buy a house, the CPF typically covers both the down payment and the monthly mortgage. Because the Singapore government also builds most of the housing in the city, homes also tend to be priced at levels that typical workers can afford.

“You don’t really have to come up with cash,” Phang says.

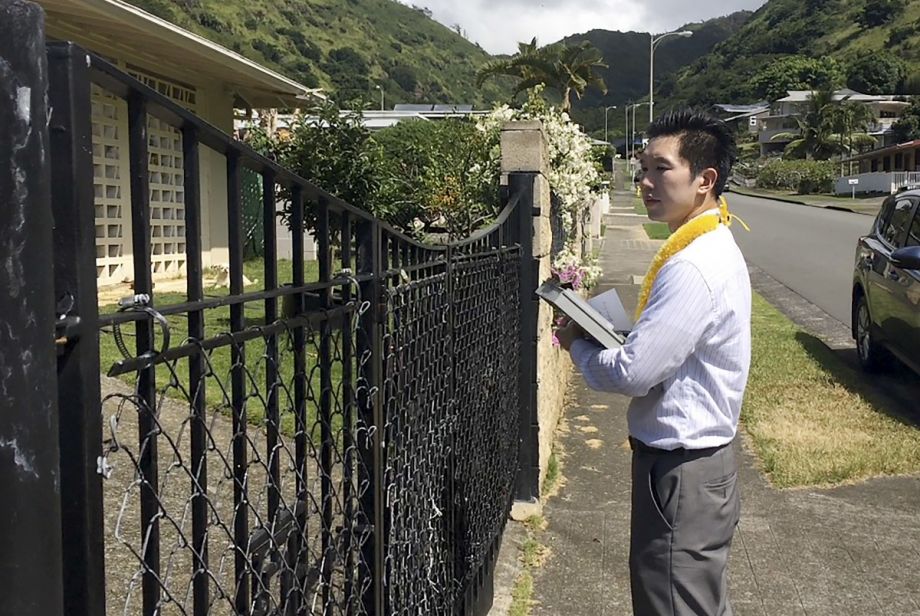

This scenario — abundant housing, publicly owned, accessible to virtually everyone in the country — was so enticing to Hawaii State Senator Stanley Chang that, in 2019, he took a delegation of 45 lawmakers, developers, and transit and housing agency leaders to visit Singapore in person. Chang was the sponsor of a program called ALOHA Homes (Affordable, Locally Owned Homes for All), which called for the Hawaiian government to build new housing on a mass scale on state-owned lands near transit stations. Under the proposal, as Next City covered, the state would build some 67,500 housing units, enough to cover its entire shortage, and make them available to anyone, regardless of income, at around $300,000 a year. The legislation died once the pandemic began. But Chang recently reintroduced it.

The package includes a bill that would establish a system of housing savings accounts, inspired by the CPF in Singapore, to help Hawaii residents budget for housing. Like the other aspects of the program, Chang has tried to adapt the idea for an American context. Instead of requiring contributions from both employers and workers, the bill would require employers to offer a housing savings account to each employee, and allow both parties to choose how much to contribute into it. The default contribution for workers would be 5 percent of income, which they could increase or reduce. (Research has shown that when workers are automatically enrolled in retirement plans with a choice to opt out, participation tends to remain high.)

The funds would technically be unrestricted and workers could use them on anything they want. But Chang says that simply calling it a housing account would be a kind of psychological trick to help people think about budgeting for housing. He thinks it would benefit low- and moderate-income people the most.

“These are often the people that have the hardest time saving for a downpayment or a security deposit,” Chang says. “It will benefit them because those funds are going to accumulate without the participant even thinking about it, without having to do anything. That’s a feature of Social Security and Medicare — there’s no paperwork to do.”

Of course, a voluntary 5-percent housing savings account in a state with a severe housing shortage is much different from a compulsory 37-percent savings account — roughly, as contributions vary with the age of the worker and are subject to caps — in a country where the government builds all the housing it needs to meet demand. And Singapore’s system took some time to develop. After Singapore became independent in the mid-1960s, it implemented a series of programs that can be thought of as “land reform in an urban setting,” as Phang wrote in a 2016 paper on the country’s housing policies. By land area, the country is only 281 square miles, a bit smaller than Charlotte, North Carolina. The government knew that demand would rapidly increase the value of such a scarcity of land, and decided that the benefit of that increase should go to the public, Phang tells Next City. It passed a law allowing the government to acquire land from any private landowner for any public purpose, which was designed explicitly to prevent landowners from getting rich off the public’s investment. The acquisition prices were locked in place prior to when the government started buying and building. The state owned about 44% of land in Singapore in 1960, according to Phang’s research; today it owns about 90%.

“It was an unusual situation which allowed for these kinds of very radical policies to be introduced,” Phang says.

The Central Provident Fund works in tandem with the Housing & Development Board, which builds housing. At first, workers’ contribution to the CPF was 5 percent, with an additional 5 percent contribution from employers. The mandatory contribution has been raised several times over the years.

“It’s a system that has been in place for 60 years already,” Phang says. “Every decade there have been changes. It’s a dynamic system and it addresses the problems that arise in each season.”

Along with Vienna, Singapore has become a model that other countries look to when they’re trying to address their housing shortages. But a lot of the circumstances that allow the system to work are uniquely Singaporean, Phang says. And without all of them, it’s unlikely to be replicated.

“If you’re going to adopt pieces of it, it’s no longer the Singapore model,” Phang says.

Still, for Chang, there’s a lot of inspiration to take from Singapore, even if its policies can’t be imported to Hawaii perfectly. The state already owns land near the route of an under-construction rail line, and it could choose to build housing there as densely as it wants, Chang says. Some aspects of the program may be controversial in Hawaii, he says, but then, so is the current system, in which private developers build luxury housing and sell it for more than most Hawaiians can afford, foreign investors buy up condos as investments, and apartment units go vacant while people are homeless.

His ALOHA Homes package, a portion of which was approved by a state senate committee last week, is designed to be revenue neutral. The new homes would be publicly owned and sold to residents on 99-year leases, like in Singapore. And they would sell for prices that don’t require taxpayer subsidies. A lot of American lawmakers instinctually look to other states that have dealt with housing shortages to find solutions, Chang says. But the solutions, in most of the U.S., have not met the challenge.

“Why would we copy California’s policies?” Chang says. “They’ve clearly failed.”

Update: We’ve clarified details about Singapore’s savings account system.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Jared Brey is Next City's housing correspondent, based in Philadelphia. He is a former staff writer at Philadelphia magazine and PlanPhilly, and his work has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, Landscape Architecture Magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Philadelphia Weekly, and other publications.

Follow Jared .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)