Eminent domain, condemnation, annexation, racially restrictive covenants. These are a few tools that government has used to create and enforce segregation — leading to uneven wealth and opportunity — in U.S. cities, including St. Louis, the fifth most segregated city in the country. A person born in wealthy, white suburban Ladue is twice as likely to survive infancy, eight times more likely to graduate college, and will live on average 15 years longer than a person born in the poor, largely black neighborhood of St. Louis Place.

After the unrest that erupted in Ferguson following the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, the Ferguson Commission determined that segregation in the St. Louis region and the unequal outcomes it produces were key underlying factors. Last fall, a group of students from the Harvard Graduate School of Design spent a semester working on projects that attempt to respond to the commission’s call for an unflinching look at segregation in St. Louis, and propose strategies for combating it. The assignment yielded radically different proposals.

“St. Louis didn’t fall from the sky looking the way it does. It’s a product of human decisions made over a long period of time, and those decisions could have been made differently,” says Daniel D’Oca, a Harvard GSD professor who led the studio, “Affirmatively Further: Fair Housing After Ferguson.”

The name’s borrowed from HUD’s 2015 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, which requires cities receiving federal housing funds to demonstrate that their policies don’t make segregation worse. That policy will likely be under fire from incoming HUD Secretary Ben Carson, who has called AFFH “failed socialism.” Talking about that threat, outgoing Secretary Julián Castro recently told NPR, “I’d be lying if I said that I’m not concerned about the possibility of going backward, over the next four years.”

“There’s still this sense that somehow what HUD is doing — that affirmatively furthering fair housing — is ‘social engineering,’” says D’Oca, “as if the last 100 years of urban housing policy hasn’t been social engineering to create segregation in the first place.”

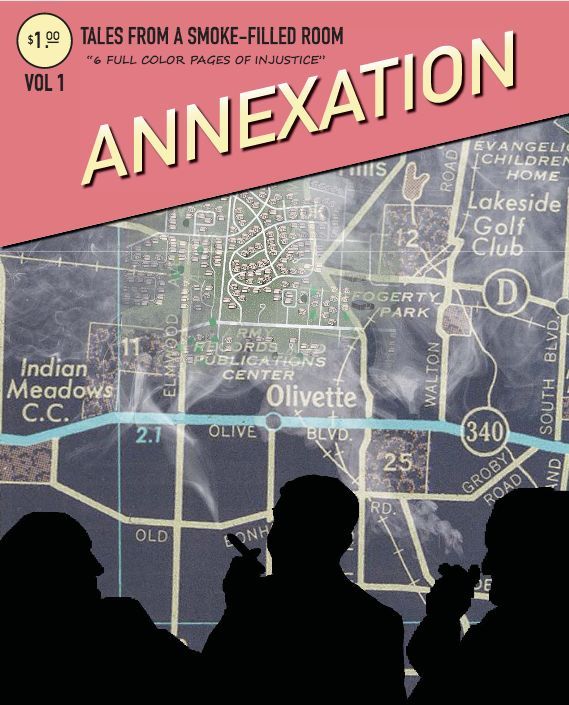

To kick off the studio, students visualized that history of intentional segregation through a series of comic books, each one tackling a different tool of exclusion. One book took on the appraisal process that led to many black people living in less advantageous neighborhoods; another explored how racist predatory lending played a role in the 2008 housing crash. The comics are informative, but also cheeky, featuring classic comic aesthetics and titles like “Tales From a Smoky Room.”

“I always knew that we had a really racist system, but I didn’t realize how intentional exclusion was,” says student Johanna Cairns. “I just didn’t realize how diabolical it was.”

After studying exclusion, the students traveled to St. Louis for a week to meet with local organizers and residents to come up with tools for inclusion. Forward Through Ferguson, established to steward the Ferguson Commission’s recommendations into reality, served as the designers’ “client,” but each student also partnered with other local groups to come up with their proposals.

David Dwight, of Forward Through Ferguson, says racial equity is the underlying goal of all 189 calls to action articulated in the Ferguson Commission’s report. FTF defines racial equity as “a future state in which outcomes cannot be predicted by race.” D’Oca’s studio also took this framework to heart. Dwight says there was concern about bringing in outside students to spend a short amount of time on issues so deeply embedded and raw in St. Louis, but that ultimately the process was successful because students responded to the needs of existing organizations and paired with people working on the ground.

Cairns, for example, was inspired by meetings with two organizations: International Institute, which resettles refugees, and Grace Hill Settlement House, which provides social services and job training for St. Louis residents. Cairns learned that International Institute is in need of an expansion and wondered if, since their missions overlapped, the two might partner to serve two communities at once.

“As we plan for the upcoming influx of immigrants resettling here, we have to create mechanisms to uplift African-American communities that have been excluded and also create places where immigrants will stay,” says Cairns.

Over 300 Syrian refugees arrived in St. Louis last year, and the mayor has supported the idea of welcoming a greater number. But Cairns and others have noted that these newcomers are being relocated to the city’s more disinvested neighborhoods and told that they will be able to move up and out as they create wealth, while the neighborhoods themselves aren’t receiving any promise of improvement. “That sends a message that [the new immigrants] don’t deserve that kind of environment, but the people that live there do,” says Cairns.

Her proposal, “A Call for Community,” suggests that the International Institute expand into the neighborhood of College Hill, where 30 percent of homes are vacant, crime is high and access to resources like healthy food is low. Through a partnership with Grace Hill, blocks could choose to opt in or out of the resettlement program. If they choose to accept refugees, they’d get access to funding that could be spent on neighborhood projects like street improvements and possibly even more personal projects like home renovations.

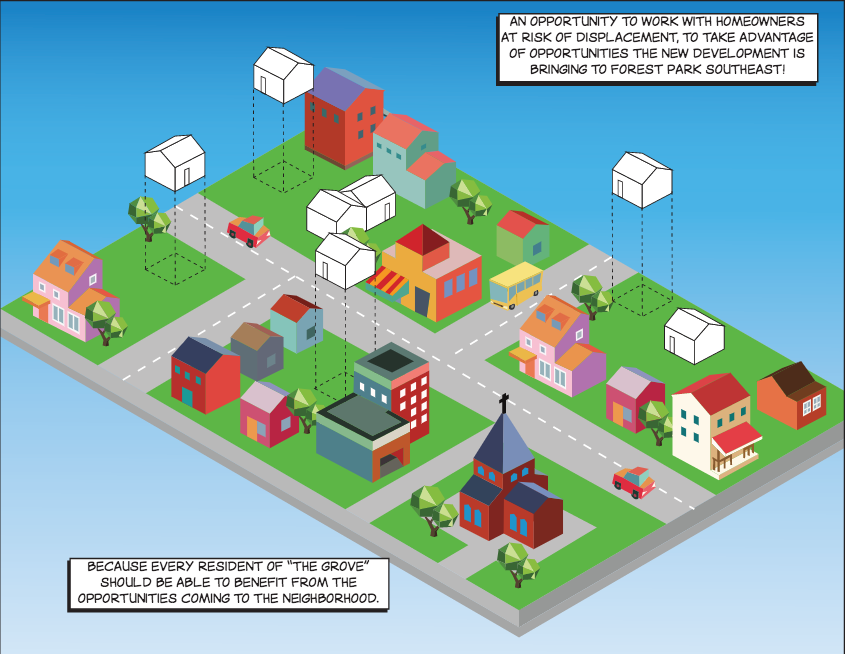

Another project, by Astrid Cam Aguinaga, focused on one of the few St. Louis neighborhoods that is gentrifying. Residents of the Grove neighborhood are overall “really positive about the development that is coming, they don’t feel they are a part of it,” says Aguinaga.

After meeting with a residents’ group called Voices of Women and Washington University in St. Louis professor Molly Metzger — and inspired by family who supported themselves in Philadelphia after moving from Peru by fixing up a house and renting out apartments — Aguinaga proposed a plan that would allow Grove residents to build modular accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in their yards and rent them out to newcomers.

Graphic from “My Grove” proposal by Astrid Cam Aguinaga

Aguinaga identified at least 50 properties in the neighborhood that could support the additions of such rentals. She also proposed a real estate transfer tax that could fund a $10,000 grant about four times a year to help residents finance the building. In addition to bringing together old and new neighbors, she says, the backyard rentals could be a way to allow older residents to remain in their homes despite shrinking families and fixed incomes.

“How can we bring power back to residents instead of just waiting for HUD to do something or for the aldermen do something, just something that they could do on their own?” she asks.

It’s a relevant question, given Ben Carson’s proclaimed stance.

“The timing is a little bit tragic,” says D’Oca of the studio’s recommendations. He anticipates that without AFFH, wealthier communities will continue to block affordable units in their neighborhoods and HUD will have no incentive to follow up on allegations of abuse, and “turn back the clock.”

At least on a local level, some students’ proposals will take shape. Cory Berg’s set of educational materials around tax increment financing will likely be adopted by Team TIF, a project by Metzger of WashU. Two students are developing a textbook about the history of planning in the region. And Forward Through Ferguson is hoping to distribute the comic books in some form, and to partner with local universities to do this type of project again. It’ll be a long haul. “The commission definitely found it would take decades to move the needle on some of these issues,” Dwight says.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)