In Forefront this week, Washington, D.C. native Dax-Devlon Ross returns to his hometown to dive below the surface-level conflict and find out what’s really going on with race, class and gentrification in the District.

Gentrification, historically, began with a block. A few intrepid outsiders moved into a shady neighborhood. They were the risk takers. They invested sweat equity and financial capital into the community. Built up the block, and then the community, with their labor. Another wave of gentrifriers followed. Recently, demographers and sociologists have identified a trend they’ve coined “new build” or “super-gentrification.” In this scenario, tax breaks and other government incentives encourage commercial investors to stimulate the local economy. They build brand-new upscale retail and residential development — condominiums for the most part — in a previously depressed but centrally located community. The city starts calling the area “revitalized” and real estate agents market it as “up and coming.” Young professionals buy in with the expectation that their property’s value will skyrocket once a few more changes occur and, for the most part, they’re right. By and large, this is what has happened in D.C.

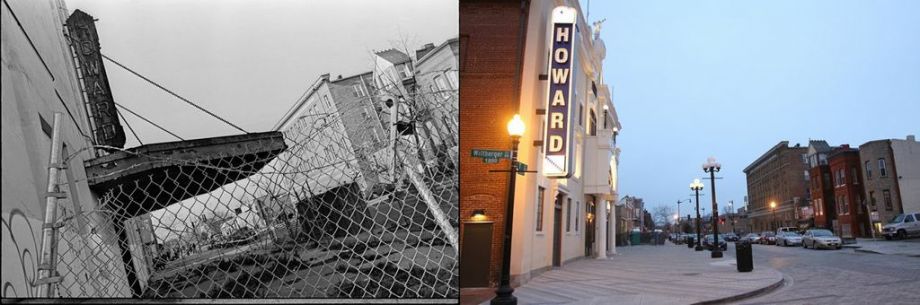

Seventy years ago, Northwest D.C.‘s 20001 zip code was the center of the city’s black intellectual and cultural life. Large tracts of the area, which includes the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights and the now-trendy U Street corridor, were destroyed in the uprisings of the 1960s and further depressed by neglect in the 1970s. Property values bottomed out in the 1980s as crime and drug use put the zip code into a sleeper hold. In the 1990s it became the site of a nightlife renaissance, but remained largely underdeveloped otherwise. By 2012, a Fordham University study had ranked the zip code as the sixth-fastest gentrifying area in the United States. New condos and retail have spurred much of that growth. In 2000, condos only accounted for 2 percent of the zip code’s home sales — six were sold in total. In 2011 alone, condos accounted for 57 percent of total home sales (276), most at triple the 2000 median price. The zip code now boasts an Ann Taylor, a Brooks Brothers, an Urban Outfitters, enough bars to serve several university populations at once and a mind-boggling 10 Starbucks.

Likewise, in the past decade the zip code’s demographic character has been inverted. We can start with education. In 2000, 11 percent of 20001 residents had a bachelor’s degree. By 2011, 25 percent held graduate degrees. The spike in education levels in turn triggered a wholesale switch in the zip code’s income levels. In the years between 2000 and 2011, the number and percentage of households earning $100,000 or more rose from 787 (6.6 percent) to 5,548 (35 percent) and median household incomes jumped nearly $50,000. Consistent with the average American’s perception and experience of gentrification, the zip code’s growth and change coincided with the departure of blacks and the arrival of whites. According to the most recent ACS data, some 7,500 blacks have disappeared from the 20001 zip code in the past decade, while some 9,000 whites have moved in. Whites now make up 33 percent of the population, which is 28 percent more than a decade ago. More than a quarter of the city’s total population growth between 2000 and 2010 happened in this single 2.6-square-mile area.

What’s telling about the zip code’s “new build” makeover is that it did not move the poverty needle. The zip code’s poverty rate is exactly what it was in 1980, 1990 and 2000 — 28 percent — and the child poverty rate is nearly twice what it was in 1990 (45 percent). This, I would contend, is the overlooked consequence of super-gentrification. Two different groups with two very different experiences of America are thrown together. Even though neither group’s members identify themselves as being wealthy, one at least has the education and social and cultural capital that allows it to access resources that can, in turn, make the neighborhood more desirable and expensive. Meanwhile, the other group has a sense of ownership over blocks and rowhomes kept intact despite deep challenges and very little support. No one was painting bike lanes or donating sidewalk garbage receptacles in 1980.

Both groups feel entitled and resent the other’s sense of entitlement. Over time the neighborhood’s revitalization engineers a rigid caste system eerily reminiscent of pre-1965 America. You see it in bars, churches, restaurants and bookstores. You see it in the buildings people live in and where people do their shopping. In fact, other than public space, little is shared in the neighborhood. Not resources. Not opportunities. Not the kind of social capital that is vital for social mobility. Not even words. Hence, stagnant poverty figures.

The “Parcel 42” affair is a prime example of what happens when these disconnected and unevenly resourced realities bump against each other. In 2007, the District selected a patch of city-owned land on 7th and R streets to build a $28 million mixed-use affordable housing project. The building was supposed consist of 112 apartments priced for renters earning up to 60 percent of the $107,500 area median income (AMI), or $64,500. The building would offer four rent tiers and reserve 16 units for tenants making 30 percent or less than the area median income. The plan sparked a contentious debate. The chair of the local Advisory Neighborhood Committee (ANC) — major players in each neighborhood’s development planning, though they wield no direct ability to enact policy — called the building a repeat of “the affordable housing built in the 1970s and 1980s that was so terribly unattractive.” Others flooded the blogosphere with their displeasure. Nearly all of their doom-and-gloom forecasts concerned design aesthetics, building amenities and the threat that a 100 percent affordable housing unit posed to the community. Meanwhile, One DC, a Shaw-based community group, staged protests and advocacy campaigns to keep the proposed project in place. The group saw the building as both a way for residents to get a foothold in the middle class and to ensure racial and social equity as the city prospers.

“There is a huge divide in D.C. between what is deemed ‘white liberalism’ and ‘black liberalism,’” said a city official who has worked intimately on D.C.‘s economic development policy and strategy over the past decade. Agreeing to an interview only on the condition of anonymity, he epitomized the conflicted space many lifelong residents I spoke to hold but are reluctant to articulate on the record. Like many 30- and 40-something African Americans who grew up in the District and went off to college in the 1980s and 1990s (like me, in other words), he has fond memories of a city most Americans jeered and avoided. He loved go-go music as a teenager and is proud he was raised in a majority black town. As an adult, he’s embraced the new D.C. — the one with rooftop lounges, cafés and chain sports bars — but is frustrated that the forces that have shaped city policy have stripped away so much of the African-American history and culture.

“On a national political level, we’ve always been and always will be Democratic,” he told me. “But when you go down into the local landscape or subscribe to the policy of all politics are local, that liberalism has a divide. White liberals in D.C. don’t give a shit about social services because they’re not of that element. White liberals in D.C. are more about quality-of-life issues as it relates to the lifestyle they want to have. It is bike lanes. It is dog parks. It is about state-of-the-art swimming facilities. It is about recreation centers. Capital Bikeshare. Car2Go. Streetcars. It’s about a way of life. Black folks want this stuff, they’re just not as passionate about it.”

Instead, many black residents want to know why the city seems to be bending over backwards to accommodate newcomers when they and their neighbors are struggling to simply survive.

“The problem is that the game has changed and we have a whole side of town, philosophically, that is still calling 1968 play calls,” the city official said. “One of my biggest frustrations has been that community leaders, pastors and non-profit leaders all come from this place of fear.”

The evolution of Parcel 42 illustrates the disconnect between competing definitions of liberalism in the new D.C. The original developer waffled on its promise for affordable housing once the complaints started rolling in. Negotiations broke down. The city blamed the developer and the developer blamed the city. Five years went by and the lot remained undeveloped. Then, last spring, the city solicited new development plans that only asked candidates to “maximize” the number of affordable housing units at or below 80 percent of the AMI ($86,000), but requiring no specific number or percentage of such units. In December, the ANC threw its weight behind a plan to build a 102-room hotel, a modest 22 units of affordable housing and ground floor retail that includes a trendy Milk & Honey Market. After its decision, the ANC expressed that one of the plan’s selling points was that the 24-hour hotel operation would increase security at the corner. The D.C. City Council is expected to affirm the ANC vote this spring.

The way the Parcel 42 deal has ultimately shaken out is a telltale sign of who does and does not have a power in the new D.C. Last year, two black city council members, both seen as strong advocates for affordable housing and equity in education and employment, copped to fraud and embezzlement charges. Both gave up their seat. Adding insult to injury, Mayor Vincent Gray — an African American who ran on a neo-civil rights platform — has been embroiled in an ongoing federal investigation into his connection to a shadow campaign that smeared his predecessor, Adrian Fenty, and led to questionable hires in his administration. Around these parts, even the whiff of corruption can unsettle city leaders. It has the potential to resuscitate the haze of impropriety that reduced the city’s credit rating to junk status during Marion Barry’s reign and automatically renews fears of another federal takeover. Any hope Gray has of losing the shady-dealings stigma and avoiding a one-term mayoralty now rests in his ability to keep the investment community happy, a fact made abundantly clear in his new 116-page, full-color, infographic-laden five-year economic development strategy. The document’s audacious “100,000 new jobs/$1 billion in tax revenue” slogan appears to advance the same vision Williams put forth a decade ago, just with less divisive language, “new jobs” having replaced “new residents.”

In his role, my source has seen firsthand the toll these scandals have taken on issues like affordable housing. “Leadership has been weakened,” he acknowledged. “When you’re sitting across from a developer trying to hold firm to something that you know is right, you can’t. The authority is not there.”

To read more, subscribe to Forefront. Already a subscriber? Click here to continue reading.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)