One of the more salacious details to come out this year about mismanagement at Metra, Chicago’s primary commuter regional rail agency, involves a job applicant with no particular qualifications. He showed up to his interview wearing a hat that read, “Fuck You.” And he was hired. It turns out he was just one of hundreds of patronage workers brought on by Metra on the recommendation of powerful politicians over the years. The practice was so routine that the agency kept three filing boxes full of index cards to record all the workers that, in local parlance, “somebody sent.”

Now, after facing criticism over corruption and its commitment to old, even outdated, technologies and operations for years, the nation’s largest commuter rail operation outside New York may be turning a corner.

After a tumultuous few years in which one executive director under investigation for corruption killed himself by stepping in front of one of his own trains, the next was bought out of his job by the agency’s Board of Directors with more than $700,000 in hush money, and nearly half the board was pressured to resign, Metra finally has leadership with bona fide reformer credentials, and something very much resembling momentum. The agency is in the midst of crafting a new strategic plan — incredibly, the first in its 30-year history — and on Oct. 9th it released details on a new capital plan to modernize its fleet. The agency is finally looking toward the future.

The question, of course, is what it sees. While most local coverage has centered on the capital plan’s fare hikes, which add up to 68 percent over 10 years, the larger issue is what kind of service the Chicago region wants to get out of Metra’s nearly 500 miles of track and 240 stations. (The Chicago Transit Authority, or the CTA, operates the city’s eight el train routes and its buses.)

Why Now

For a number of reasons, this seems like an auspicious moment to think big: Not only has Metra cleaned house, but the release of a report by Governor Pat Quinn’s special transit task force earlier this year (prompted in part by the agency’s very public meltdowns) has made service and governance reform a hot topic. More excitingly, the Transit Future campaign — launched in April with the goal of creating a dedicated stream of revenue for public transit in Chicago’s Cook County — has secured the public endorsement of 12 of 17 county commissioners, and may significantly increase the region’s transit resources as soon as late next year.

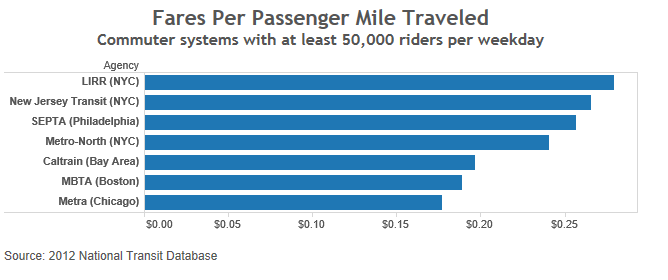

So far, Metra’s boldest move has been announcing 10 years of fare increases to raise its own much-needed revenue. Predictably, riders have objected. But Metra points out, accurately, that its fares are among the lowest in the country: A monthly pass to travel roughly 10 miles out from the city center is $121 in Chicago, but nearly $200 in New York and Boston. Moreover, the agency’s capital needs are tremendous; the Regional Transportation Administration estimates there’s a backlog of $9.9 billion just to reach a state of good repair over the next 10 years. Much of the new revenue will go toward buying new train sets, replacing some of the 50-year-old cars that make up one of the oldest train fleets in the country.

Rethinking Strategy

The rest of Metra’s strategic plan is unlikely to make waves. The centerpiece is a list of 10 goals, most of which hew to the most fundamental principles of good management: safety, financial stability, efficiency, effective communication, and so on.

Kyle Smith, a project manager at Chicago’s Center for Neighborhood Technology, a prominent research and advocacy group on transit issues and a partner with Transit Future, would like to see the agency do more. “One thing we would really like to see be a priority is transit-oriented development,” he says, pointing to a CNT report last year that found Chicago was one of the few American cities with significant rail transit infrastructure to build more housing outside the orbit of train stations than in them. “Compared to a lot of other commuter systems, Metra is doing far less to use its assets and tools to attract and facilitate redevelopment.”

Smith points out that one major hurdle for TOD — an FTA rule that any redeveloped park-and-ride lots replace lost parking spaces one-for-one nearby — was recently removed. “The time to act,” he says, “is now.”

In addition, Smith says the agency could do a better job of making sure its stations, which “run the gamut in terms of quality,” appear safe and comfortable to riders, and of doing more with potentially valuable infrastructure. The South Chicago line, for example, runs through dense neighborhoods along the city’s south lakefront, but hour-long waits outside rush hour mean it’s relatively little used. “That’s a transit asset most cities would kill for,” he says. “And it’s not elevated as a mobility option the way it should be.”

The governor’s Northeastearn Illinois Transit Task Force report echoed those concerns. “Infrequent Metra service…can make transit an unreliable option,” they wrote. “It is even harder to use much of the system for non-commute trips. … Because many Metra lines have headways of two hours or longer on the weekend, transit is less convenient for trips spent grocery shopping, visiting family, or accessing recreational space.”

A Model to the North

One model solution may lie just on the other side of the Great Lakes. Toronto’s GO Transit is in the midst of a radical transformation from the sort of traditional commuter service Metra now provides to a “regional express rail” system that provides reliable round-the-clock service across the greater Toronto area. Last year, off-peak frequency on the two busiest lines was increased from hourly to half-hourly, and the Ontario provincial government has committed itself to a multi-billion-dollar plan, called “The Big Move,” to eventually introduce 15-minute waits on all seven lines. The idea is that transit shouldn’t just be a convenient option for the city’s growing downtown population, or 9-to-5 commuters, but for everyone in the region.

“We’re playing catch-up,” says Anne Marie Aikins, a spokesperson for GO Transit. “For 20 to 30 years we didn’t have any investment, and we’ve fallen behind.” Over that time, Aikins explains, the region’s rapid growth created unbearable traffic congestion: “It had become, and still is, impacting people’s daily lives. It impacts our level of business, our health, our ability to work, everything. We’re in the midst of elections this year, and it’s the most important topic. I think people appreciate how important [transit] is to people’s daily lives.”

It’s not clear how easily Chicago could launch its own “Big Move.” While locals love to complain about traffic, congestion and transit have yet to become central campaign issues. Service innovations like increased frequency don’t yet appear anywhere in the strategic plan, and a Metra spokesperson confirmed that the agency has no plans to move in that direction. In August, Streetsblog Chicago reported that one board member flatly rejected that kind of service expansion, claiming that running a single extra train during rush hour would cost over $30 million. (Aikins, however, reports that GO Transit spent just $7.7 annually to adopt half-hourly frequencies on its two biggest lines.)

There are also structural barriers: Metra doesn’t own all of its tracks, and some carry freight trains that would interfere with frequent service. But even on the lines it does own — including South Chicago — Metra’s governance structure makes regional, big-picture planning difficult. Unlike GO Transit, which is run by the province of Ontario, a controlling share of Metra’s board is appointed by suburban officials, who have historically shown more interest in competing with the city for dollars than collaborating on a regional transit strategy.

The serious turbulence the region has experienced in accomplishing a project far less ambitious than regional express rail — a unified transit fare card — illustrates the problem. Back in 2011, the Illinois General Assembly passed a law mandating that the three major transit operators in the Chicago area (Metra, the CTA and Pace, which runs suburban buses) work together to have a single fare card by January 1, 2015. Pace and the CTA collaborated from the start on a new payment system called Ventra, and have been in compliance since late last year.

Metra, however, initially declined to join Ventra. Unlike Pace and the CTA, whose customers have been tapping or swiping cards to board vehicles for years, Metra still sells paper tickets, sometimes at stations but more often through conductors on moving trains. It has been famously impervious to change: Credit cards only became an accepted form of payment — and only at certain stations — in 2010.

In October, Metra announced that it already considered itself in compliance with the state mandate, because Ventra cards — which have an optional debit card feature most users haven’t activated — can be used to buy tickets at locations where credit cards are accepted. It has also announced plans to create a smartphone app-based ticketing system with Ventra transit accounts. What will be done for the region’s many residents who don’t own a smartphone, however, is unclear. What is clear is that a lack of cooperation has so far prevented Chicagoans from enjoying an integrated fare system.

Still, after years of scandal, any forward progress is welcome. The truth is that Metra’s emergence from a dark period in its history simply marks the beginning of a new period of debate and competing visions for its hundreds of thousands of daily riders, and hundreds of thousands more who live, work, and study near its stations but don’t find the service convenient enough to use. The future of transit in the Chicago region depends, in large part, on which ideas win out.

Daniel Kay Hertz is a student at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. He writes at danielkayhertz.com.