Geography is a strong indicator of economic upward mobility, according to a new study from leading American economists. The researchers mined millions of anonymous earning records to compare upward mobility across metropolitan regions in the U.S. Where exactly you grow up has a large bearing on what tax bracket you might climb to as an adult.

That might sound like common sense, but until now there hasn’t been strong data to prove it. The researchers found that upward mobility is much higher in cities where poor families are more integrated into mixed-income neighborhoods. In other words, living in a neighborhood where people hold all sorts of jobs and earn varied wages gives poor children a better chance of digging themselves out of poverty and earning more as adults.

This is an idea I’ve been thinking about for a while, and wrote about earlier this month in a piece about another recent study that pointed to inclusion as the significant predictor of economic success in cities:

In 2006, Federal Reserve economists conducted an analysis of about 120 metro areas across the U.S. by looking at variables that influence local economic growth. The result? “A skilled workforce, high levels of racial inclusion and progress on income equality correlate strongly and positively with economic growth,” Benner and Pastor write.

This new study, which the New York Times outfitted with some amazing interactive graphics, essentially proves that theory: Low-income kids living in cities where people of a mix of incomes live in closer proximity have a better chance of succeeding than kids in more economically segregated cities.

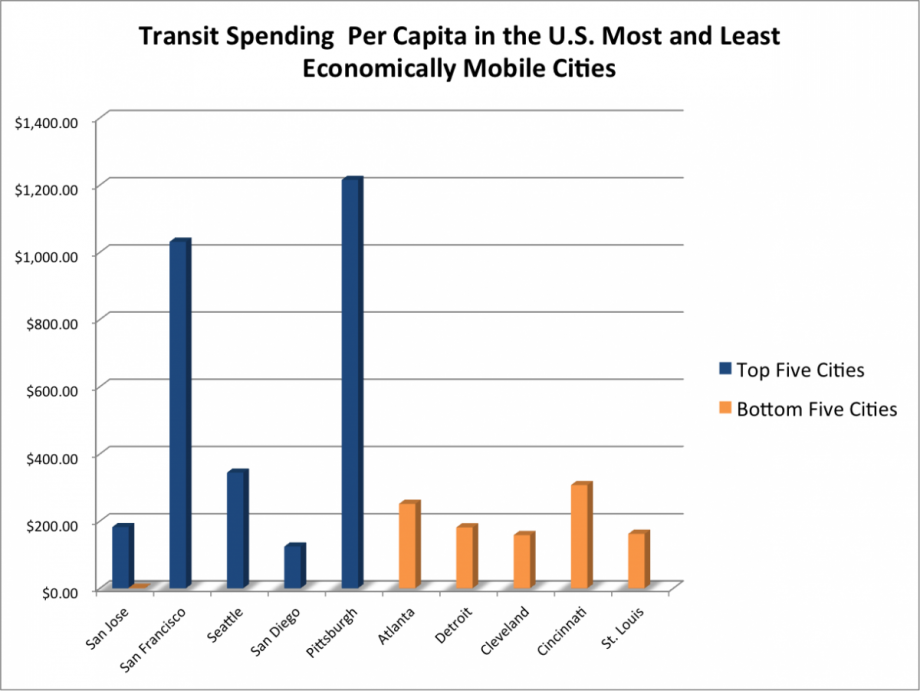

But the Times, which spoke with an Atlanta area woman about her insanely long commute (“a bus, two trains and another bus”), got us thinking: How much does easy access to transit foster upward mobility? The study ranked 30 cities according to the chances of rising up if you were raised in the bottom fifth of income earners (that is, if your parents make less than $25,000 a year). We looked at the top five cities and bottom five cities on the list and calculated the per-capita investment in their regional mass transit authority’s operating budget.

Credit: Next City/Ben O’Neil

Top Five Cities

- San Jose

Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority

Annual operating budget: $341.7 million

Per capita spending:$381.67$181.68

- San Francisco

San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency

Annual operating budget: $851.1 million

Per capita spending:$1030.55

- Seattle

Sound Transit

Annual operating budget: $212 million

Per capita spending: $343.87

- San Diego

San Diego Metropolitan Transit System

Annual operating budget: $243 million

Per capita spending:$76.48$123.97

- Pittsburgh

Port Authority of Allegheny County

Annual operating budget: $372.1 million

Per capita spending:$1215.17$262.92

Bottom Five Cities

- Atlanta

Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority

Annual operating budget: $426.1 million

Per capita spending: $250.58

- Detroit

Detroit Department of Transportation

Annual operating budget: $128 million

Per capita spending: $181.30

- Cleveland

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority

Annual operating budget: $237 million

Per capita spending: $158

- Cincinnati

Cincinnati Metro

Annual operating budget: $91 million

Per capita spending: $306.86

- St. Louis

Metro Transit St. Louis

Annual operating budget: $249 million

Per capita spending:$782.595$161.68

Now, it’s worth noting from the outset that these numbers don’t tell the whole story. The San Francisco stats only include Muni’s operating budget, not BART’s, which brings many workers of various economic backgrounds into San Francisco every day. I’ve ridden both San Diego and Detroit’s mass transit, and though this number might lead you to believe that Detroit’s is better or a larger priority for the city, it’s not. San Diego’s transit was much more pleasant and timely, but those buses don’t have to travel the 139 square miles that make up Detroit’s vast footprint. Seattle and Pittsburgh are more reliant on cars, yes, but it can’t be denied how much money they’ve invested in regional transit. Seattle, much like San Francisco with BART, has two regional transportation authorities.

But even if the numbers are raw and rudimentary and have a couple outliers (St. Louis San Jose and San Diego, specifically), it’s still worth considering. It seems fairly simple: When everyone has access to some form of mass transportation, it gives them access to jobs they might not otherwise have applied for.

This is part of the problem in Detroit now. There are many Detroiters looking for jobs, but few jobs exist in the city. There are jobs in the surrounding suburbs, but no reliable form of transit to get there without a car.

If a region allocates more resources to mass transit, it gives residents in the urban core a better chance of climbing to a higher income bracket. Instead, we have large concentrations of poverty across the country with few reliable transportation options, and little chance at either physical or economic mobility.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.