Charley Cummings had a vision of creating a new, sustainable, local food system. In 2013 he and his wife started their own company in Concord, New Hampshire, delivering grass-fed beef and pasture-raised pork and chicken purchased from farmers in the region and delivered directly to consumers. Along the way, he’s found farmers, food processors, distributors and consumers who are excited to be part of it.

But the banks haven’t been interested.

“There were farmers and also other types of food businesses, processors and things that wanted to scale alongside us, but seem to have trouble accessing the right type of capital,” says Cummings, who previously worked in commercial composting and management consulting. “We found ourselves sort of lending to these businesses in one form or another, often in the form of pre-payments on our buying commitments.”

Unlike the rest of the country, Cummings found, the northeast no longer has a commercial bank that specializes in food and agriculture lending. There’s the farm credit system, established by Congress more than a century ago to provide financing for farmers and the food industry — but like the broader banking system, farm credit entities have consolidated. There once were eight farm credit entities serving the northeast, but by the time Cummings launched his company there was only one; it had grown in size to the point where it wasn’t interested in working with the smaller farms and food companies working with Cummings.

“That left a gap in the market for small- and mid-scale producers and also other value chain participants that aren’t well addressed by farm credit either, like manufacturers, distributors, consumer brands, trade brands,” Cummings says.

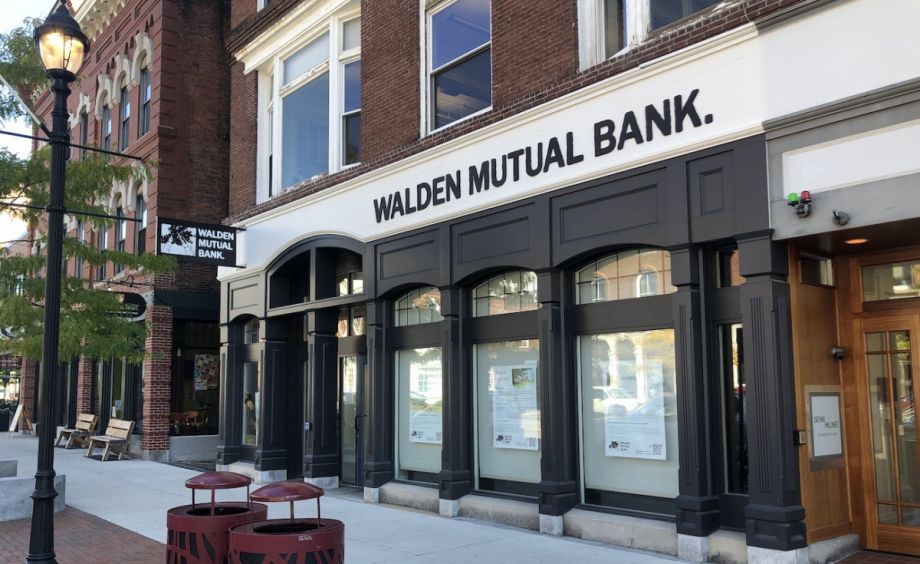

To fill in that niche, Cummings landed on a very old solution: a mutual bank. It’s a bank that doesn’t have conventional shareholders. Instead it’s owned and controlled by its depositors, similar to a credit union. Walden Mutual Bank opened for business in October 2022, becoming the first mutual bank to open its doors since 1973. Specializing in local food and agriculture lending across New England and New York, it already has more than a thousand depositors and $44 million in assets, including loans to farmers, organic food production facilities and even a project to build a solar array over a sheep grazing meadow to add some income for the farmer.

“The reason we’re structured as a mutual is because it’s intended to be permanent,” Cummings says. “The mutual bank model has proven its longevity and the structure gives the impact mission of the bank teeth from a governance perspective in a way that shareholder ownership does not.”

(Photo courtesy Walden Mutual Bank)

The long history of mutual banks in the U.S. begins in 1816, as a chapter in perhaps the longest running big city rivalry in the country. That was the year the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society, better known as PSFS, became the country’s first mutual bank to receive deposits, followed the next year by Boston’s Provident Institution for Savings.

Though they have sometimes fallen short of their original social mission, mutual banks emerged as a way for working class or poorer households — often recent immigrants — to pool their savings, earning a modest amount of interest while investing in each others’ homes. They clustered in the northeast because during the 19th and early 20th century it was the country’s most populated region, with new immigrants coming over from Europe in waves. As of 1914, mutual banks held a majority of deposits across the six New England states, including 76% of deposits in New Hampshire, 70% in Connecticut and 53% in Massachusetts. Out of 640 mutual banks across the entire country in 1914, 597 were in New England, New York, New Jersey or Pennsylvania.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation today lists 427 mutual banks across 43 states, though they’re still largely concentrated geographically in the northeast, Ohio or Illinois. Without the pressure to grow and generate profits for shareholders, mutual banks are mostly smaller institutions focusing on a specific geographic market.

For Cummings, the appeal of the mutual bank model came in large part from the prevalence of cooperatives in the agriculture space. Grocery store shelves everywhere are lined with products from farmer-owned cooperatives like Ocean Spray, Land-O-Lakes and Organic Valley. The remaining farm credit entities across the country are also technically producer-owned cooperative financial institutions. Rural electric cooperatives have a long history of delivering power to farmers and rural towns across the country. Farmers and food entrepreneurs have a history of trust and doing business with cooperatives.

Cummings did look into starting a credit union, which is a much more common example of a cooperatively-owned and -governed financial institution, but there are a few reasons why it wasn’t quite a fit. Regulators generally don’t allow new credit unions to do commercial lending in their first two or three years. Beyond that, current laws limit credit union business lending to 12.25% of their assets unless a majority of their members come from low-income census tracts. These restrictions just didn’t make sense for a new financial institution whose core business was going to be agriculture and food businesses.

“It was in that context that I came across the mutual structure in banking, which is very much akin to a credit union,” Cummings says. “It just sort of fits into a different regulatory bucket, but they’re very similar from a structural perspective.”

Until Walden Mutual, the most recently-chartered mutual bank was Volunteer Federal Savings Bank, which opened its doors in 1973 in Madisonville, Tennessee. For many decades, banking regulators and policymakers got caught up in an ideological backlash against the mutual bank model, fueled by the idea that all companies including banks were better off putting profits for shareholders above all else. Nobody currently involved in approving new bank applications at the New Hampshire Banking Department or the FDIC had any experience with reviewing an application from a mutual bank, and both agencies would have to sign off before the bank could open for business.

As it turned out, the two things that might have separately lowered the chances of Walden Mutual ever opening for business — its ownership structure and its mission — actually ended up feeding into each other as strengths to get through the application process and raise the startup capital for the bank.

The main issue for state and federal banking regulators was that, since 1973, banking regulations have changed significantly, especially after the financial crisis a decade ago. Regulators today require banks to have much higher capital levels — meaning dollars retained from profits or raised from selling shares to investors. Since mutual banks don’t have conventional shareholders they can call upon to boost capital levels when needed, they can run into difficulty maintaining required capital levels, leading many mutuals to convert into conventional shareholder-owned banks.

For a prospective new mutual bank, it wasn’t clear if it would be able to raise enough startup capital to comply with modern capital requirements. It took more than the usual amount of convincing just to give Walden Mutual the chance to find startup investors who would be willing to limit their own returns so the bank could retain enough earnings to stay in compliance.

But it turns out having a clear social mission protected by a mutual structure was a big draw for the growing segment of ESG investors — the acronym is short for “environmental, social and governance.”

Walden Mutual was able to raise $25 million in “special deposits” to use as startup capital. The special deposits are not insured by the FDIC, and they can’t be sold for a higher price later like stock shares, but they do earn a modest return based on the bank’s profitability over time.

“There was an element of the regulators sort of scratching their head to say, like, ‘well, who is investing in this if you’re not gonna sell it?’” Cummings says. “That took a lot of time to explain there’s this large community of people that are investing with a view to a set of impacts they want to see in the world. And they want a financial return, but they also want a non-financial return in the form of this very positive, tangible impact in the community.”

The investors and regulators were also both convinced that the bank’s board and management had sufficient experience and relationships in sustainable farming, food production and retail to be able to assess potential borrowers and underwrite loans successfully in this growing niche of the food world. Besides Cummings’ own prior experience running a sustainable meat company, the board includes several others with experience working in and or doing business with organic farmers or local food companies. It was also important that others on the bank’s proposed executive team include people with experience in banking generally, beyond local or organic foods. The team came together through social networks, including many whom Cummings didn’t know until he started organizing the bank.

“There is a massive amount of bureaucracy, for lack of a better word, that you need to build before you can even open the doors,” Cummings says. “And I’m not at all saying that’s not necessary. Banks operate in this realm of being akin to a public utility, you’re being given a license to operate with a guarantee from the government and so that has to come with very significant strings. There’s a lot of investors particularly in the venture world that are like, ‘well, why would you ever go through that process when you can just start a neobank and rent someone else’s charter and then essentially fly under the radar?’”

It would have been much easier to just start some kind of unregulated investment fund, pooling capital from a bunch of wealthy families, foundations, corporations or large banks and turning around to make loans to farmers and other food businesses in the supply chain. And there are such funds that can work with new or early stage businesses that are too new for any bank to work with, even Walden Mutual. Cummings says he has a bench of business partners whom the bank can bring in to make those earlier stage investments as needed.

But Cummings believes that such investment funds would be insufficient to scale up the local food ecosystem. At some point, every business needs a bank loan, but not every bank is structured specifically to understand and work with local and sustainable farmers and food businesses.

“My view of what would unlock a much more significant rate of growth in this ecosystem was an entity that could lower its total cost of capital significantly,” Cummings says. “And so where does the lowest cost of capital come from? Federally insured deposits.”

With an FDIC-insured bank, he says, you have an entity with a lower cost of capital than the government itself. “Our theory of change is that by lowering the cost of capital for these types of farms and businesses, we can really help the ecosystem to grow.”

Since the dramatic failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank earlier this year, Cummings says it’s been an unexpected boost for Walden Mutual as both individuals and businesses have been actively thinking more deeply about finding a bank that is more aligned with their values.

“There’s nothing more strategically aligned in financial services than saying to a potential depositor, ‘hey, there’s nobody else here, we work for you and in your best interests,’” Cummings says. “Whereas with a shareholder-owned bank, that is not always the case.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)