Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

AP Photo/Keith Srakocic

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberAbout an hour north of Pittsburgh, the former manufacturing hub of Butler, Pennsylvania, once produced everything from glass to the very first Jeep. Starting in the 1930s, the city’s minor league baseball team played in Pullman Park, named for the famous train cars it produced. The best players were called up to the Yankees, and today, the bar across the street, My Buddy’s, is still decorated with a mural depicting the New York team’s mid-century stars. Above the painting’s baseball diamond, steelworkers labor eternally in the red glow of a furnace.

Butler is one of Pennsylvania’s dozens of small industrial cities that face a future, and present, with little industrial employment. Its population peaked during World War II at about 25,000, and has since fallen to 13,757 (as of the 2010 Census). The story will sound familiar to Pennsylvania residents from the far northwestern city of Erie to Philadelphia in the southeastern corner of the map. The Keystone State used to be one of the mightiest industrial economies in the United States. Before the oil shocks of the 1970s and the collapse of the steel industry in the 1980s, it lagged behind only New York and California in population size. Today Pennsylvania has dropped to number six; the people, and the power, long ago shifted to the suburbs.

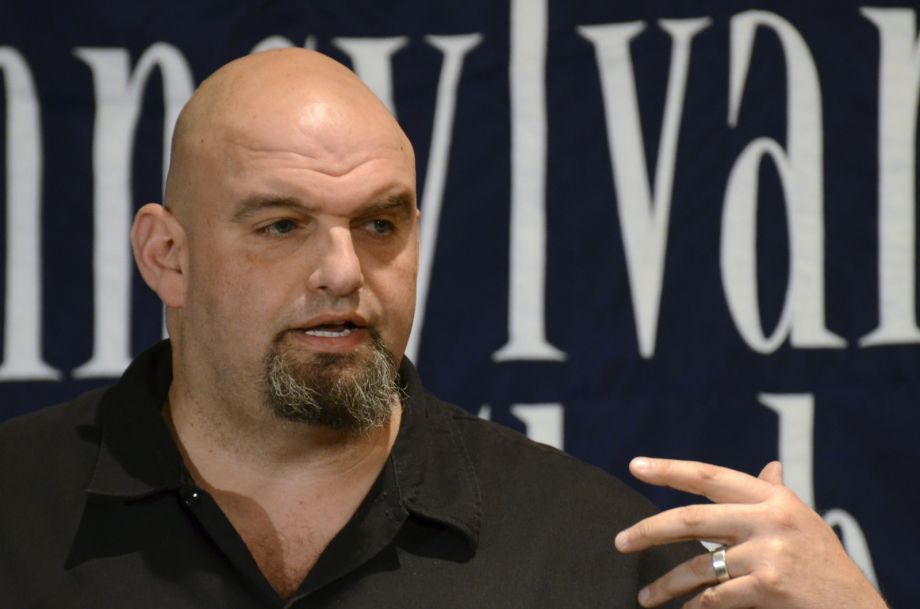

All of these stats make Butler the perfect stage for a stump speech by John Fetterman, who is running in Pennsylvania’s April 26 Democratic primary for a U.S. Senate nomination. (Whoever is chosen will face incumbent Republican Pat Toomey in November.) In mid-March, Fetterman, the mayor of the small steel town of Braddock, also near Pittsburgh, attended a candidate forum at Kelly Automotive Park (the former Pullman Park, now with car dealership branding).

“Braddock is a stark, tough place,” Fetterman said. Once comparably sized to industrial-era Butler, it has shrunk to a little over 2,100 residents. “It is the poorest community in Allegheny County, and one of the poorest in the entire commonwealth.”

The U.S. Steel Edgar Thomson plant at work in Braddock (AP Photo/Andrew Rush)

His talk wasn’t all gloom; he got some laughs from the audience too. His delivery was markedly better than six months earlier, at the start of his campaign. Back then he told his story with a kind of subdued awkwardness, untempered by the near-constant buzz of low-level national media attention that has accompanied his decade as Braddock’s mayor.

The centerpiece of his speech contrasted Fetterman’s privileged youth in south-central Pennsylvania (his family owns an insurance business) with that of a kid he met while working for Big Brothers, Big Sisters. The 8-year-old’s father had died of complications from AIDS; his mother would soon succumb too. From her hospital bed, she made Fetterman promise to get her son into college. The encounter made an impression.

“I want to be a champion for Pennsylvania’s forgotten cities, just the way I’ve been a champion for Braddock,” Fetterman said, wrapping up his speech in Butler. “I don’t have all these endorsements, I’m not an establishment candidate. I’m running an authentic race coming from a community that is at the very bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. I want to be a champion for cities like Braddock, like Butler.” Standing at an imposing 6-foot-8-inches, with tattoo-covered arms (one is Braddock’s ZIP code, another set are dates of homicides that happened there during his watch), Fetterman is an unconventional candidate for Pennsylvania. But this is an unconventional election cycle.

Braddock Mayor John Fetterman has the city's ZIP code tattooed on his arm. (AP Photo/Andrew Rush)

Fetterman has endorsed Bernie Sanders, the democratic socialist from Vermont, a $15 minimum wage and the legalization of marijuana. Beyond pitching himself as the candidate of Pennsylvania’s urban areas, he maintains he represents those who have been left behind by deindustrialization, capital flight and the growth of the exurbs. “No community deserves to be abandoned,” his first ad says. It’s a message that resonates in the aftermath of the poisoning of Flint, Michigan.

“This year more than any year, people want an authentic voice, they want something true,” Fetterman says one March afternoon in his home across from a steel mill. He’s dressed in his uniform of a black Dickies work shirt, black jeans, and black and yellow New Balance sneakers (made in America, he notes). “If you live in Pennsylvania you either live in struggling city, or you used to. Or you know someone, like your parents, who lives in one.”

Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill opened in 1875 next to the sluggish Monongahela River in western Pennsylvania, and Braddock grew up around it. The Mon Valley became the epicenter of the industry, producing roughly half of the nation’s steel by the early 1900s, its mills providing over 80,000 jobs at mid-century. That number slowly sapped until the big collapse of the Ronald Reagan years. By 1987, only 4,000 steel jobs remained. Pittsburgh managed to survive because of its educational and medical institutions, but the Mon Valley’s economy collapsed. Carnegie’s original mill in Braddock, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, is the last in the state. Few, if any, of the workers live in what remains of the town. (Fetterman lives across the street, in a repurposed Chevy dealership.)

Suburbanization had already humbled Braddock well before the steel industry collapsed. The median household income is $24,000, and the poverty rate is more than twice the national figure. The majority-black city’s once-bustling main drag is utterly devoid of private businesses on its eastern half-mile, from the steel mill to the Steel City Pawnbroker.

“I wish I could see a path back, but a city needs something to make it go and it’s not clear Braddock has anything like that,” says Alan Mallach, economist and senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress. “When you have 2,000 people in a city that once had 21,000, and you’ve got no economic base, it gets really extreme.”

Fetterman hasn’t reversed Braddock’s continuing population decline, but it’s hard to argue he hasn’t improved the lives of those who remain. He moved there in 2001 to work as an AmeriCorps volunteer, after earning a master’s in public policy from Harvard. During his time at the university, Fetterman says, a speech by Robert McNamara was the single most formative event. One line in particular stands out to Fetterman from the former defense secretary’s memoir: “We were wrong, terribly wrong. We owe it to future generations to explain why.”

“I can’t make Braddock perfect, I can’t make it like it was 50 years ago. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try. That doesn’t mean I don’t have a moral obligation to try.”

When Fetterman arrived in Braddock he helped start a GED program in town and his students convinced him to run for mayor. As he tells almost every audience, he proceeded to win the 2005 election by one vote. His subsequent two elections were won handily.

“People told me I wasn’t going to make a difference,” says Fetterman. “Well, I can’t make Braddock perfect, I can’t make it like it was 50 years ago. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try. That doesn’t mean I don’t have a moral obligation to try.”

From early on in his mayoralty, Fetterman attracted national media attention, much of it fawning. The exception is a 2011 New York Times Magazine piece, “Mayor of Rust,” which noted some of the limitations of his position. The role of mayor in Braddock is largely ceremonial and power lies with city council, but that doesn’t mean much in a city with an annual budget of less than $2 million. There is no power in Braddock, so Fetterman uses his privileged connections and the media’s interest in his image to draw resources from foundations, companies and his family (who have funded much of his nonprofit work and his living expenses). He even gives money to local residents in need. Myasia Cherry, who received $500 from the mayor to help cover her college tuition told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “There’s a lot of rich and flashy politicians, but he’s not one of them. … He’s an angel.”

Fetterman brought a visibility to the town that eludes neighboring municipalities like Rankin or Duquesne. The Levi’s jeans company approached Fetterman after reading about him in The Atlantic. They used Braddock in an advertising campaign, paid residents to serve as models, and funded a new community center and a new playground. He has proven adept at drawing resources to the town. The “Braddock Promise” college aid program Fetterman launched in 2015 (based on a successful program in Pittsburgh) has raised more than $300,000 for scholarships through crowdfunding and philanthropy.

The mayor also put his supersized reputation to use when the town’s hospital shut down. He was arrested for protesting the closure, and then worked successfully to bring an urgent care center and affordable housing to Braddock to replace it. There are a few artists and urban homesteaders who have moved to town because of Fetterman’s rallying call, along with a handful of artisanal businesses like Studebaker Metals and the justly acclaimed craft beer company, Brew Gentlemen. (The $6 drinks keep many away, but it is one of the only businesses that stay open past 5 p.m.)

In addition to bringing foundation dollars and a few new businesses and organizations to town, Fetterman points to his record on law and order as an example of an issue of importance to the Democratic Party that he has practically engaged with (in a fashion neither of his opponents have). He claims that violence is down in Braddock, and credits that to a community policing style encouraged by the police chief and himself.

“We were able to remove those officers who were not model officers,” says Fetterman. “We hired really great officers who I think best embody this promotion of de-escalation. We want both parties to be able to walk away with their dignity intact. Making an arrest should be the last option pursued. Look what happened with Sandra Bland; you had somebody who didn’t use a turn signal and it escalated to arrest and her suicide. Not everything should be actionable.”

Fetterman likes to say he ran for mayor because it afforded him a “bully pulpit.” His Senate campaign is premised on the idea that as a representative of the true Pennsylvania, he could score more wins for the Braddocks of the state with a much bigger megaphone. The relative intimacy of the 100-person Senate chamber, where idiosyncratic figures have historically thrived, could be a much better fit. The upper chamber allows individual legislators the opportunity for star-making turns in a fashion that would be impossible in the more regimented and far more populous House of Representatives. The Senate also provides a national stage that can be used to highlight the issues facing residents from Braddock to North Philadelphia.

Braddock Mayor John Fetterman speaks at a Pennsylvania Press Club luncheon on Feb. 22. (AP Photo/Marc Levy)

“I am running because I want to be able to bring in more resources and more attention,” says Fetterman. “We need a Marshall Plan of reinvestment in these communities across the country.”

A Marshall Plan for the cities was first proposed by the Urban League and other civil rights groups in the 1960s, taken up by Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey, and echoed by the left wing of the party. Fetterman’s call is a rhetorical gesture that recalls a more liberal version of the Democrats and one far more in line with the policies of Bernie Sanders than Hillary Clinton.

“Broadly speaking, he means private dollars will only follow public dollars in communities that are upside-down like Braddock or McKeesport,” Fetterman’s press representative, Leslie Wertheimer, explains in an email.

The original Marshall Plan sent more than $130 billion in today’s dollars to the battle-scarred nations of Western Europe after World War II, acting as seed money to get private enterprise back on its feet. That’s what Fetterman envisions for areas like Braddock and western Pennsylvania.

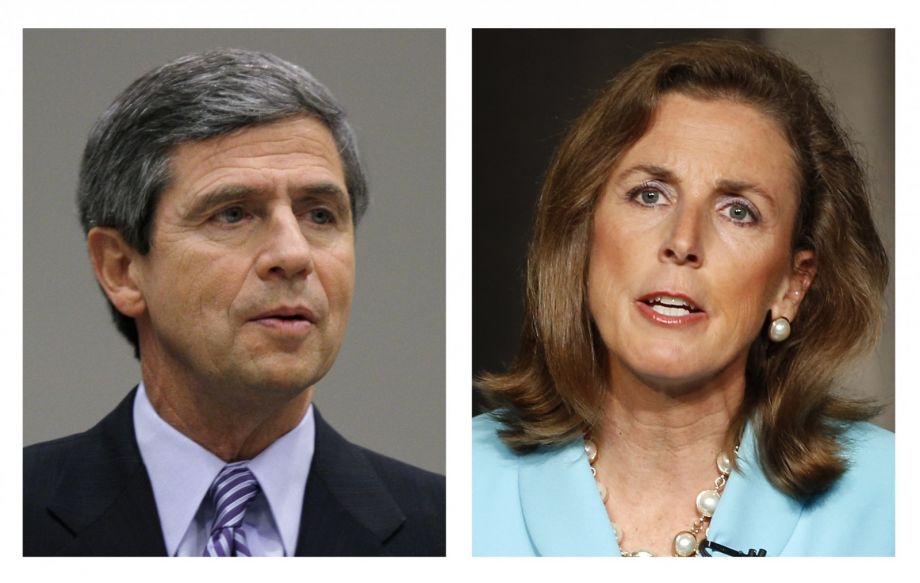

Winning the Democratic nod for the Pennsylvania senator is far from a home run for Fetterman, but he jumped into the race because the two other Democratic candidates have substantial weaknesses. There’s a degree of fatigue with Joe Sestak, who has seemingly been running for office for a decade and lost to Toomey in 2010. Katie McGinty’s first TV ad, showing her touring a fake-looking factory, is basically just a litany of Democratic catchphrases. Plus, this is a strange election cycle, by all accounts, and perhaps one where a candidate who refuses to wear a suit and tie could be victorious.

“Look what’s going on with Bernie Sanders or the Republican side with Trump. It’s territory we’ve never been in before,” says Terry Madonna, director of the Franklin and Marshall college poll. “You can’t rule out anything. This year political scientists have to throw out the rulebook.”

Still, Pennsylvania is a big state and television ads are needed to get a candidate’s name and message out. For all the magazine profiles, talk show appearances and Twitter chatter, Fetterman still isn’t a known quantity. An April 2 poll shows just 9 percent of those surveyed saying they would vote for Fetterman. And in late March, President Barack Obama endorsed McGinty.

Democratic senate candidates Joe Sestak and Katie McGinty are running against Fetterman for their party's nomination in the April 26, 2016 primary. The winner will aim to unseat Republican U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey in the fall. (AP Photo)

Fetterman’s hope rests in first-time voters — the larger the turnout, the better he is expected to do — and his alliance with Bernie Sanders (another former mayor). His campaign is coordinating with Sanders’ support networks in the major metropolitan areas, like Philadelphia for Sanders and Burghers for Bernie. Although his opponents are both from the Philadelphia area, and are expected to do well there, Fetterman could break through with large concentrations of young or very liberal voters in the eastern city’s university neighborhoods.

“Sestak has problems with the establishment and McGinty’s campaign seems lackluster, so this might be the time for a non-traditional candidate like Fetterman,” says John Kennedy, associate professor of political scientist at West Chester University and longtime observer of state politics.

At home in Braddock, where he’s not an unknown, the mayor naturally has supporters and critics. He also has a fractured relationship with the city council. “A lot of people like him here, but a lot dislike him too,” explains one resident. Critics point to one controversial incident in particular.

On a frigid January day in 2013, Fetterman heard what sounded like automatic weapon fire and saw a masked man running. The mayor put his son inside, called the cops, grabbed his shotgun and drove off in pursuit. When he intercepted the man, Fetterman leapt from his vehicle, shotgun in hand. Officers arrived and didn’t find any weapon on the man, who was then released. He told WTAE at the time that the mayor leveled the weapon at him (Fetterman denies this), that the sound of gunfire was kids playing with bottle rockets, and that he was jogging with facial gear on to protect against the cold. Neither man was charged. (For his part, Fetterman says he made the right call. “This was three weeks after the Sandy Hook massacre and this individual was all in black, running from a scene running towards our elementary school.”)

Still, in a year when Bernie Sanders’ message of Wall Street reform continues to resonate with primary voters, Fetterman’s opponents live in suburban communities where the median household income is over $100,000. Though he’s a self-declared “son of privilege,” the mayor of struggling Braddock can’t be accused of living lavishly among the ruins: His chief asset is his house, worth an estimated $120,900. The mayor’s position pays $150 a month, and Fetterman seems to live off of a modest stipend from his wealthy parents (about $54,000 last year, although they are also contributing mightily to his campaign despite being staunch Republicans).

“I took this job because I really believe in the mission,” Fetterman says of being mayor. “No city should be left behind. Flint, Michigan, shouldn’t have been a surprise. We have issues like that all across Pennsylvania, especially in communities like Braddock. Ride down the Mon Valley and the further you go the more desperate people get. That’s what motivates me. It’s not that I want a nice office on Capitol Hill. I’m going to live here as long as I’m around.”

If Fetterman can conquer his name recognition problem across the state, his message about the need for an equitable economy — with a focus on urban reinvestment — could hit home with Pennsylvanians. When all three Senate candidates spoke to a packed house in North Philadelphia recently, the crowd received Fetterman enthusiastically. (He joked that Braddock “isn’t as nice as North Philadelphia,” which drew laughter.)

Afterward, some audience members said they were very impressed by the mayor’s message.

“He would get my vote,” said one North Philadelphia woman. “When [McGinty] got up, I felt like she was kind of scripted. One of the first things she said was ‘black lives matter.’ It felt like she was just saying that because everyone here is black. He’s serious. I never heard of Braddock before, but I can imagine it because he described it so vividly. I believe in him.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine