Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

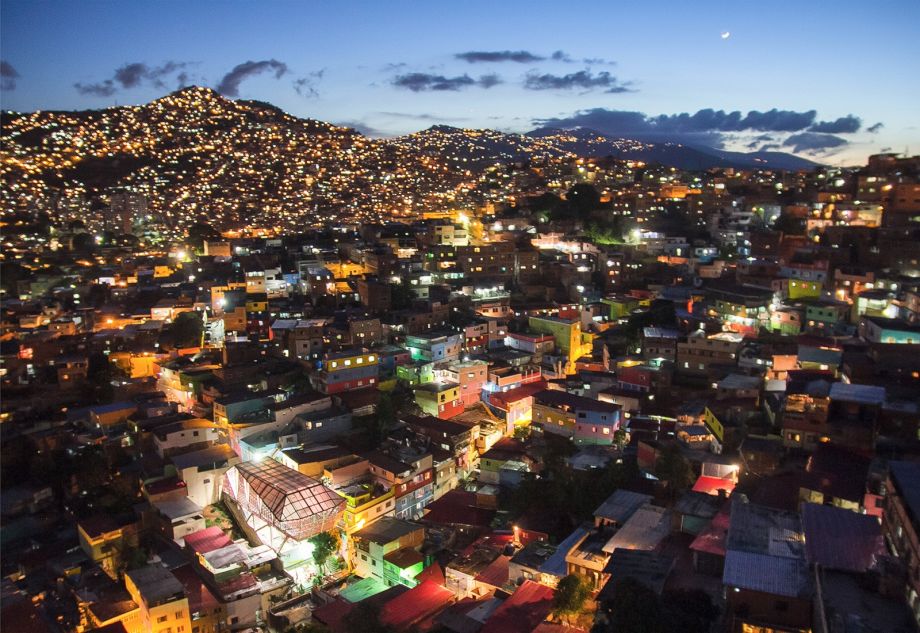

Become A MemberWedged into a steep, narrow slope amid an ocean of tin-roofed and cinderblock ranchos that extend across Caracas’ northwesternmost barrios, the Eleonel Herrera sports complex opened in December 2014 to the resounding cheers of residents. “This is a court for peace … a court for life,” proclaimed the municipal mayor to the crowd as he gave president Maduro a televised tour of “the spaceship.” It’s how some have dubbed the futuristic sports complex designed by Alejandro Haiek, a local architect who has been collaborating on community-led projects in the barrios of his hometown for over a decade.

Cleverly woven into the existing urban fabric, the complex’s cantilevered basketball court hovers over a multipurpose community center and ground floor bakery. A winding barrio stairwell that residents use as a street to access their homes is part of the building, connecting residents to the center while integrating it into a well-used piece of community infrastructure. The insect-like structure — built mostly from recycled and prefabricated metal parts — has become a defining landmark in the Caracas skyline and on the international design circuit, making Haiek into something of an inadvertent starchitect for the ethical practice set.

The Eleonel Herrera sports complex designed by LAB.PRO.FAB sits in the residential neighborhood of Lomas de Urdaneta. (Photo by Irina Urriola)

Yet in the densely populated Lomas de Urdaneta neighborhood, Haiek’s otherworldly architecture is most important for its most fundamental basic asset: the basketball court.

“Before, we had to walk for nearly a mile to find the nearest court,” says Zair Navas, a former basketball player who grew up in the neighborhood and is part of the Carbonell Collective, a community group devoted to sports and culture that spearheaded the project 15 years ago.

Navas remembers being turned away from those courts — poor barrio kids like him weren’t welcome in the middle-class developments they were part of. Now in his early forties, Navas and his generation are making sure their children don’t suffer the same fate.

“This is our way of fighting violence,” explains Navas, “by cultivating peaceful citizens.”

Haiek met Navas in 2008, by which time the community had improvised an open-air court with little more than a basketball hoop on a scarcely 20-foot-wide leftover patch of dirt between ranchos where the new center stands today. The two struck up a conversation after accidentally bumping into each other on the subway – recent TV coverage about the collective’s protest to local authorities had already sparked Haiek’s interest – and after visiting the site and learning more about their story, Haiek joined their efforts to realize a dream that the community had been struggling towards for decades.

It’s the kind of casual encounter that typically kickstarts any of Haiek’s collaborations, and a fundamental ingredient of his democratic approach to building. By connecting with communities first as a citizen — rather than as an expert — he is able to better understand the social dynamics of the context and develop the personal relationships needed to break down the traditional hierarchy between architect and client.

“It’s not this top-down model that assigns sterile spots to architects that have no relationship with the community and don’t recognize their demands,” says Haiek.

That Haiek has been able to collaborate so successfully with communities like Lomas de Urdaneta is no small victory for an architect who believes in building change from the ground up. In 1996, fresh out of the Universidad Central de Venezuela, Haiek cofounded his design practice, LAB.PRO.FAB, with a mission to produce architecture that serves the public — “for the masses, not mass production,” as he puts it. The neoliberalist policies and modernist vision that had shaped Latin American cities over the last 50 years had proved wasteful, divisive and prosperous only for a few. Master plans had excluded the masses, and the sprawling slums of his native Caracas were glaring proof.

Today, 60 percent of the city’s residents live in self-built neighborhoods like Lomas de Urdaneta. In these fast-growing areas, the lack of safe, public spaces and recreational facilities exacerbates vulnerability to crime and reduces access to opportunities that are found in more established parts of the city.

Rather than just building for these communities, Haiek believed in empowering them. In his manifesto — The Public Machinery — he describes architecture as a “foundation for a collective and participatory democracy,” a vehicle for voicing the needs of marginalized populations, materializing their demands, and integrating their knowledge. Whether it is a basketball court, a public square or a cultural venue, it isn’t the physical space itself, but the collective process leading up to and following its creation that transforms the lives of its users — all the way from the decision-making phase through to its design, construction and management, Haiek argues.

The architect sees the value of his contribution in designing that process — what he calls a “logistical chain of events.” And that, in his mind, is the hardest part. “Building human relations is not as easy as building buildings,” Haiek, the son of civil engineers, often says.

None of Haiek’s projects illustrates this as clearly as Tiuna el Fuerte Cultural Park, an experiment in tactical urbanism that has gradually evolved into an acclaimed public space where Caracas youth can come for free public art and dance activities. Started up by a number of local art collectives as an improvised concert space on an abandoned parking lot in the El Valle section of Caracas, it has become an important alternative to the city’s violent streets thanks to the self-governing network of artists, academics and NGOs that runs it.

The Tiuna el Fuerte Cultural Park hosts free urban art and dance classes for youth in the barrio. (Photo by Julio César Mesa)

Like his collaboration with Navas, Haiek’s entrée into the park project came out of a friendship. When he met the artists who would become his partners on the project and learned about their ambition to create a performance space, he didn’t hesitate to join their cause. “These are communities that nobody wants to work with,” he says of the gritty ensemble of graffiti artists, breakdancers and hip-hop musicians including “Piki” Figueroa, whose band Bituaya has since risen to the international stage. Native to El Valle, one of the city’s most musically rich neighborhoods, the collectives represented the vibrant underground art scene that surfaced on the street corners of every barrio across the city, but that was typically excluded from the institutional art circuit.

As Haiek’s first self-managed community project, it served as a testing ground for many of the strategies he would replicate in future projects.

Exploiting spatial opportunities was one of them. Using President Hugo Chavez’s controversial squatting policy to their advantage, they occupied a defunct bus station situated at the intersection of two motorways dividing the barrio from the formal city. It’s an example of what Haiek terms “urban accidents,” or the residual, underutilized spaces typically found along highway infrastructure. As unregulated territories — like those of the informal city — they offered room for experimentation.

“Architecture still operates under the same logic that produced these voids, instead of using them as opportunities to reprogram the city,” says Haiek. “What we try to do is create protocols for occupying interstitial landscapes to form new ecosystems rather than just buildings,” he told Metropolis in 2015.

When it came time to build, he encouraged a model of “instant microurbanism” that created temporary infrastructure using tents, abandoned buses and projection screens. That approach allowed artists to use the space as it developed.

Haiek and the collectives also came with their own model for financing the project. Together with communities, the architect submits all of his projects for approval through Venezuela’s system of communal councils, or local governing bodies through which residents can devise, vote on and access state funds for community projects. Implemented by Chavez in 2006 and modeled on Porto Alegre’s highly successful participatory budgeting scheme, they are a central tenet of the late president’s bid to shift the locus of power to the people.

But while the public money was an important piece of financing and a way to ensure community participation in the project, it wasn’t enough to see even a fraction of the project through completion. Again, they looked to the system for opportunities. If the revolution’s socialist policies were largely failing those whom they promised to serve, then perhaps it was time to rework them. The architect worked with Tiuna members to appeal to corporate social responsibility laws to receive in-kind donations from companies, like the shipping containers that they repurposed into offices and classrooms, or the cranes that they used to stack them into place.

Haiek is quick to dispel any assumptions of his choice to use shipping containers as anything other than pragmatic. “We didn’t use containers because they were trendy; we used them because they were the building blocks made available to us.”

Recycling wasn’t just a cost-saving measure, it was also a part of the LAB.PRO.FAB’s ecological ethos. Large tires were converted into tree planters, and wooden pallets were used to build a vertical garden of indigenous plants — a garden that has since flourished into a micro-ecosystem and attracted native bird species in a city where green spaces are scarce.

For both Haiek and the Tiuna el Fuerte collectives, the practice was also a vindication of their socio-political beliefs.

Lorena Freitez, one of the collective’s founding members (now head of the newly created Ministry of Urban Agriculture) has described their process as one of deliberate inclusion.

“We wanted to create an alternative use or value to those materials and people that have been excluded from the formal discourse of the city,” Freitez told the authors of Design Like You Give a Damn 2, an anthology of socially conscious design published by Architecture for Humanity.

Haiek’s “upcyling” of local skills — not just materials — is central to his design ethic, and the binding agent that sustains projects over time. His design process invariably begins with an extensive study of a community’s local intelligence to develop what he calls a cartography of talents.

“We don’t come in with sophisticated architectural plans; we bring an idea and a certain technical knowledge that we then cross with those of local craftsworkers,” he explains. Both designer and builder learn from each other, resulting in more effective buildings that members of the community are equipped to maintain in the future.

Eudis Rodríguez is a blacksmith working on Haiek’s latest project, an industrial park and civic center in Barquisimeto, a city in northwestern Venezuela, west of Caracas. He says it has been a learning experience. “I was trained old school, so I was used to working only with perpendicular lines,” he says, referring to Haiek’s unconventional designs and use of triangulated forms. “We have this joke that he tells me he draws in 3D and I tell him it must be 4D, because it’s just so different from what I’m used to.”

Children play at the Industrial Park in Los Cerrajones, a project by insitu, Oficina Informal, LAB.PRO.FAB. Espacios de Paz 2015. (Photo by Irina Urriola)

By the same token, Haiek finds his practice — and buildings — nourished by the indigenous skill sets of tradesmen that go as far back as three generations.

In the case of Tiuna, you could say the project has, for the most part, built itself. Workshops run to teach skilled trades such as carpentry and metalwork were geared at producing park elements like staircases and windows. A group of graffiti artists, with minimal technical support from Haiek and his team, built their own screen-printing shop. Local ironsmiths even devised their own tools to bend the discarded tailpipes that they welded into stair rails. The task proved an exercise in creativity that elevated their craft beyond the repetition of hard, manual labor. One metalworker put it this way: “Before it was my hands that hurt, but now it is my brain that hurts.” His metalworking company’s new business card proudly reads “Herrería Creativa,” or Creative Ironwork.

The sense of ownership is also evident in the park’s activities, with initiatives like the Laboratory of Urban Arts run by artists who use facilities like the recording studio in exchange for teaching youth. It’s just one of numerous user-generated programs that have resulted in tangible impacts on the community. Radio Verdura, a mobile radio show hosted from a repurposed vegetable truck, periodically broadcasts from detention centers in the barrio to give juvenile offenders access to culture and self-expression.

Haiek says that while some of these young men have tragically died trying to escape the cycle of violence, others have managed to trade their gun for a microphone. “Thanks to Tiuna el Fuerte, some of these ‘bad guys’ are now cultural leaders in their communities,” he says.

For most architects, the biggest challenge in working in tight-knit communities like these is building trust. But for Haiek that is a consequence, not a means to an end. “It’s not so much about building trust as it is about identifying with their struggle, taking on their problems as our problems. If you are a part of that, then there is no distance between you and them. Trust comes not from your good intentions, but from your actions over time, when the community sees that you are in it for reasons that have nothing to do with money or success.”

Before there was any talk of a cultural park at Tiuna El Fuerte, Haiek got to know the art community after attending their concerts and street gigs. They hit it off. Elemc, a rap artist and one of Tiuna’s most vocal members, recalls their encounter with the architect. “Alejandro was a heaven-sent for us,” she says. “From the beginning he understood our dynamic and we realized that we had common goals.”

Over a decade later, Tiuna el Fuerte is still a work-in-progress that Haiek is very much a part of, and that long-term commitment has earned him a reputation among communities in various barrios.

“We become part of the community, and part of its decision-making process,” Haiek says.

The process is often slow and cumbersome, involving weekly meetings where representatives of up to 400 families debate which projects get the green light, and like most things in Venezuela, susceptible to clientelism and graft. But by and large, communal councils have been credited with completing thousands of community projects and enabling previously marginalised sections of the population to engage in collective decision-making in ways it never had before.

For Haiek, the councils have not only ensured that projects are validated and thus embraced by the larger community, but also legitimized and defended his role professionally: In one project — a botanical square for the El Valle Parish — council members pressured the government into hiring him as the architect. When officials deemed that kind of relationship with their constituents a little too close for comfort and later banned him from the construction site, the community lashed out in protest by blocking the street and burning tires. As a result, heads rolled and Haiek was reinstated.

“I think Chavez may not have anticipated the degree to which people could organize and manage the transformation of their spaces, to the point of making such specific demands from their leaders,” says Haiek.

Although he steers clear of political affiliations — he believes “the world is more complex than left or right” — Haiek considers the communal councils established by the popularly voted Constitution a key element of Chavez’s deeply contested legacy.

Thanks to that legal framework, he has been able to make use of state funds to self-manage projects with communities which have gone on, as in the case of the sports center, to be adopted by state-run social programs — known as missions — like the Gran Misión Barrio Nuevo Barrio Tricolor aimed at upgrading and beautifying poor neighborhoods.

“The government has realized how effective we are in working with communities,” says Haiek, who realizes that official support comes with the risk of being co-opted by a political ideology. In a country where any success remotely tied to socialist policies is ripe for agitprop, Haiek’s architecture has already been labeled by government as “Revolutionary.” But while the government may use his work to push their own agenda, Haiek points out that his process also responds to the failures of the revolution. Despite the government’s pledge of allegiance to the poor, an estimated 80 percent of the population still live below the poverty line, while crime has soared to an all-time high and the economy has all but imploded.

“We want to question the state not by opposing it, but by showing how their participatory framework can be leveraged to generate these transformations,” Haiek says. Grassroots urbanism, he says, can shape policymaking.

Yet to be sure, it will take much more than these citizen-led acts of urban acupuncture to improve the living conditions of the world’s 1 billion-and-counting slum-dwellers. Even Haiek admits his projects are just a drop in the bucket.

Latin American planning expert and professor Clara Irazabal says these initiatives need to form part of an integrated, citywide strategy “that necessarily includes government, the private sector, NGOs and communities.” Indeed, it is how a city like Medellín went from murder capital to urban success story, but a tall order for Venezuela, where bankruptcy and political polarisation are perpetual roadblocks to systemic change. Still, like Haiek, Irazabal believes in the power of collective action. “Architects, designers and planners have to join forces with communities and together, pressure elected officials to support these collective initiatives,” she says.

As settlement upgrading takes center stage this month at Habitat III, UN-Habitat’s conference on housing and sustainable urban development, bottom-up approaches like Haiek’s can provide insight to policymakers on how they can collaborate with architects and planners to facilitate and channel the energy of engaged citizens.

Back at Lomas de Urdaneta, where everyday Haiek’s “spaceship” transports dozens of kids to a world of sport and culture that their parents could only dream of, a longtime resident had this to say to a local paper: “Basketball courts like that one are rare in our neighborhoods; you won’t see a structure like that anywhere else. At night, when it lights up, it’s beautiful.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Ana Cañizares is a freelance architecture and design writer based in Barcelona.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine