In the past few years, the number of community-engaged design projects has boomed. Buoyed by good intentions and the recognition that resources in urban landscapes are still unequally distributed, designers, planners, architects and other professionally trained technical experts are working with impacted communities to prevent further harm and built more equitable cities.

But how do designers know when they are replicating harmful dynamics they wish to avoid? How can community-engaged practitioners, instead, be a part of breaking down persistent barriers and building the capacity of communities who have been denied access to resources (in some cases for generations) to take ownership of the neighborhood’s future?

Well, one thing they shouldn’t do is be a Dick. That’s the playful conclusion of a new children’s book-style guide to social impact design practice recently produced by the Equity Collective, a group of leaders and practitioners in the field of community engaged design. Available here as a free downloadable book, Dick & Rick: A Visual Primer for Social Impact Design was created with the intention of encouraging professionals in the field to practice self-reflection, remain aware of power dynamics and stay focused on an ultimate goal of advancing racial, economic and social justice in every decision made.

“The moment we are paid to go into a community, we have agency. We need to be hyper-critical about how to deploy it,” says Liz Ogbu of Studio O. “We don’t spend enough time reflecting on this in the field.”

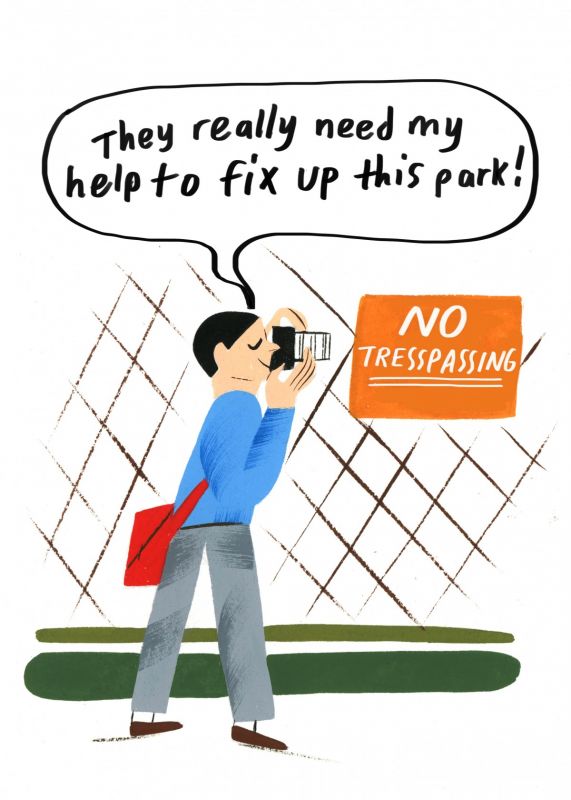

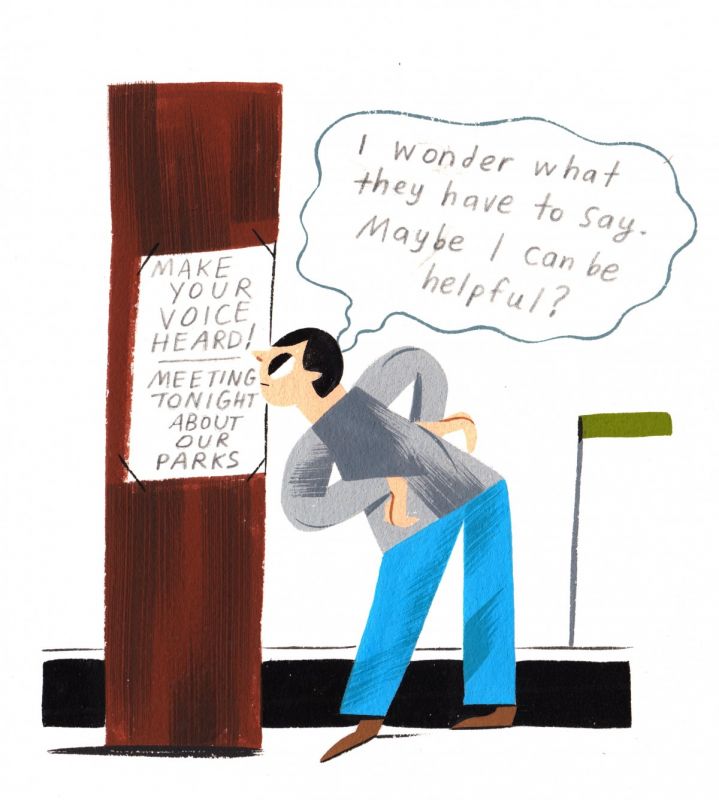

To illustrate persistent questions that designers along the way, while also injecting humor into what can often be a heavy-handed conversation, Dick & Rick uses the “Goofus and Gallant” (which you may remember from Highlight Magazine for kids) cartoon model to play two archetypes off each other.

Gallery: Dick & Rick: A Visual Primer for Social Impact Design

(Illustrations by Ping Zhu)

The booklet tells two parallel stories about designers, one named Dick, one named Rick, coming into a neighborhood and designing a park. Dick’s story is the more common one — a designer or company comes into a neighborhood and begins designing a park without ever really stopping to talk to or work with the people who live in the neighborhood. The team conducts a cursory community engagement process that only builds mistrust between designer and community, and creates a beautiful but ultimately underutilized product. The engagement ends there.

Rick’s path, on the other hand, begins when the community organization “Residents for Parks” initiates the project and solicits design expertise to work with them collaboratively. The designer approaches the community with a sense of humility, recognizing that they can bring their technical skills to supplement the skills that already exist in the community. They conduct a meaningful, long and collaborative community engagement process. Moreover, Rick is flexible, seeking to use his skills to further the community’s vision. What results from Rick’s process is a beautiful and well-used park — and so much more. Community members gain valuable technical and leadership skills, financial support and a sense of ownership over their physical space.

The Equity Collective sought specifically to raise key questions practitioners should constantly be asking themselves, including;

- Who initiated the project, and why? The authors seek to highlight whether the project began because of a real community need or for less locally meaningful reasons. “Often, designers initiate a project — and don’t verify whether there is community need or interest before doing so. This can, without intending to, trace back to a colonial attitude towards urban development and working with impacted communities,” says Christine Gaspar, Executive Director of the Center for Urban Pedagogy and one of the authors.

- How can technical experts utilize their power and privilege to support impacted communities’ power and leadership?

- What does deep versus surface-level community engagement look like? In these parallel stories, Dick practices surface-level engagement by asking residents cursory questions about the color of benches. Rick, meanwhile, uses his design skills to create an engagement process that incorporates community members’ wisdom, knowledge, and leadership in key decision-making moments.

- Who leads, and who gets paid? In the book, Rick makes a point of paying a young community member in recognition of his hard work and contributions. This was a very intentional decision, the authors say. While technical experts are usually paid for their work in design and development, community members are usually volunteering their time, an unjust dynamic that is heightened in communities that are financially under-resourced.

All of these factors lead to the big question: What is the holistic outcome of the project?

Dick’s project ends when the park is complete while Rick’s continues on, generating multiple benefits beyond the boundaries of the space and after the ribbon-cutting. For Rick, design has become a tool for acknowledging and correcting past wrongs and with that, the entire process of the project changes and the focus becomes “outcomes rather than output,” Ogbu says.

In a nod to that awareness of process, the authors worked with illustrator Ping Zhu and the Center for Urban Pedagogy to create archetypal cases for who is typically the designer and what a community typically looks like in social impact design projects. Dick and Rick are both white men and the illustrations bring up pointed issues regarding diversity in the field; in 2013, African-Americans made up just 2 percent of the number of licensed architects in the US and in 2010, 81 percent of urban planners were white in the US. Gender and class disparity continue to plague the design professions.

But rather than call out specific individuals for being Dicks, the collective created the booklet as a reminder to themselves and all colleagues in the field to constantly ask themselves, as Theresa Hwang of Dept of Places put it, “How can I be less of a Dick and more of a Rick?”

This article is part of a Next City series focused on community-engaged design made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Danya Sherman is an urban & cultural planner who specializes in collaboratively developing strategy, research, and programs that work towards a more creative and just society. She is currently a Research Consultant to ArtPlace America, the Center for Performance and Civic Practice, a contributing writer for Next City, and the Case Study Initiative Project Manager at the MIT Sam Tak Lee Real Estate Entrepreneurship Lab. Previously she founded and directed the Department of Public Programs & Community Engagement at Friends of High Line. She holds a Master's in City Planning from MIT and a Bachelor of Arts from Wesleyan University.