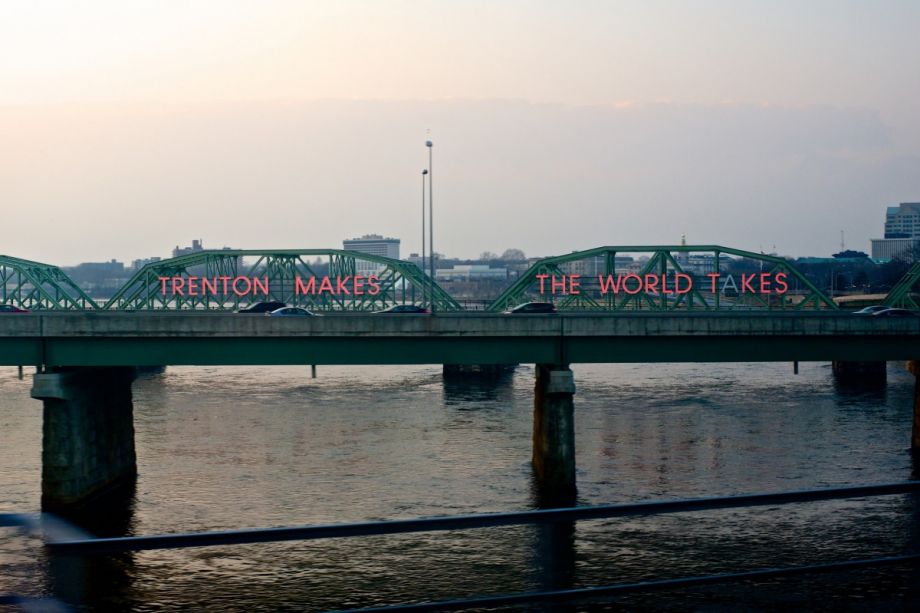

Just south of Trenton’s famous bridge, which telegraphs the message “Trenton Makes, the World Takes,” is a swath of waterfront property many agree could yield much more for New Jersey’s capital city — if only a pesky little highway could be replaced.

Cut off from the rest of downtown by Route 29, the crescent-moon-shaped tract of land hosts a minor league baseball stadium, a nightclub, an underutilized park and a handful of state agency offices. Employees overwhelmingly drive to the area and, when there’s not a game going on, leave it nearly empty after 5 o’clock.

Last month, a bill that would require those agencies to move downtown and free up their buildings for commercial waterfront development cleared the New Jersey Legislature’s Commerce and Economic Development Committee, a move Assemblyman Reed Gusciora sees as the first step to revitalization. He’s less hopeful that Route 29, long the subject of redesign studies, might be removed anytime soon.

“If you look at urban revitalization efforts around the country, much of it takes place on the waterfront,” he says. “Unfortunately … we have waterfront buildings that are harbored by the Department of Education, the IT department, and they add little benefit to the city landscape.”

He wants to see those agencies remain in Trenton, just move downtown to the Capital District area. The number of state employees in Trenton has decreased by half in recent years — from roughly 40,000 to 20,000 — leaving plenty of office space away from the waterfront.

That move would allow the city to try to attract mixed-use developments to the water’s edge instead. Once a manufacturing and industrial hub — hence the slogan emblazoned on the Lower Trenton Bridge — Trenton’s waterfront hosted steel mills and shipping ports before state departments and sports. The factories closed throughout the first half of the 20th century, and the highway-ification of Route 29 in the 1950s cut off the waterfront from the rest of the city. A 1990s improvement project added a tunnel south of the baseball stadium intended to divert truck traffic off city streets onto Route 29.

But since 9/11, Homeland Security forbids trucks from using it, leaving the $80 million tunnel obsolete save for one feature — it’s topped by a park that few currently use. “It’s really a bridge from the city to the riverbank, but because we don’t develop it, nobody really uses the park,” Gusciora says.

Removing Route 29 might be the key to increasing residents’ and developers’ interest in the area. Studies dating back to at least 1988 have explored replacing the highway with a boulevard, an idea that surges in popularity and interest in tandem with city coffers. According to the Congress for the New Urbanism, which named Route 29 as one of its 2017 “Freeways Without Futures,” replacing the highway with a surface street could open up access to 18 acres of developable land.

Despite a 2005 feasibility study, the concept languished after the 2008 recession. Then last year, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, a metropolitan organization that also covers Philadelphia and Camden, issued a $100,000 grant for the Downtown Trenton Waterfront Reclamation Redevelopment Project to explore the boulevard idea again.

“I’ve yet to see any city, small or large, that hasn’t reaped great benefit by having a waterfront that was locked away by a highway opened up, or an industrial use that was decaying opened up for public use and enjoyment,” says Roland Lewis, executive director of the Waterfront Alliance, a nonprofit that focuses on waterways and shorelines in New York and New Jersey. There’s San Francisco, which removed one of its waterfront highways in the 1990s, replacing it with public space. Seattle is in the process of doing the same.

“These cities were created because of the commerce that the waterfronts allowed,” says Lewis. Removing a highway can present challenges to state and regional mobility, but on the whole, he says, “the city gains.”

Still, even local supporters like Gusciora and George Sowa, CEO of economic development group Greater Trenton, don’t expect that transformation to start anytime soon. It’s too expensive, they say, and New Jersey’s Department of Transportation agrees.

“Realigning a highway would be a costly endeavor,” said NJDOT in a statement. “The Department must use its limited resources in the most efficient and effective way possible, with a priority given to ensuring the safety of New Jersey’s roads and bridges and maintaining these assets in a state of good repair.”

So Sowa is putting his energy into courting the development and investment communities, massaging their image of Trenton as a struggling, postindustrial city into one of an affordable, walkable community that might be attractive to young people and seniors. And Gusciora is focusing on moving the state agencies, a step he calls “more realistic” than redesigning Route 29 right now.

“I think the time is right because people are ready to reinvest into cities,” he says. Asked whether developers might be turned off because of the waterfront’s disconnect from the rest of downtown, Gusciora says he thinks they’d see the property’s value. And he hopes that successful waterfront development might encourage the state to kick in funds for the boulevard.

First, the state agencies need to go. Gusciora’s bill will next go before the full assembly, where he expects it to pass.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)