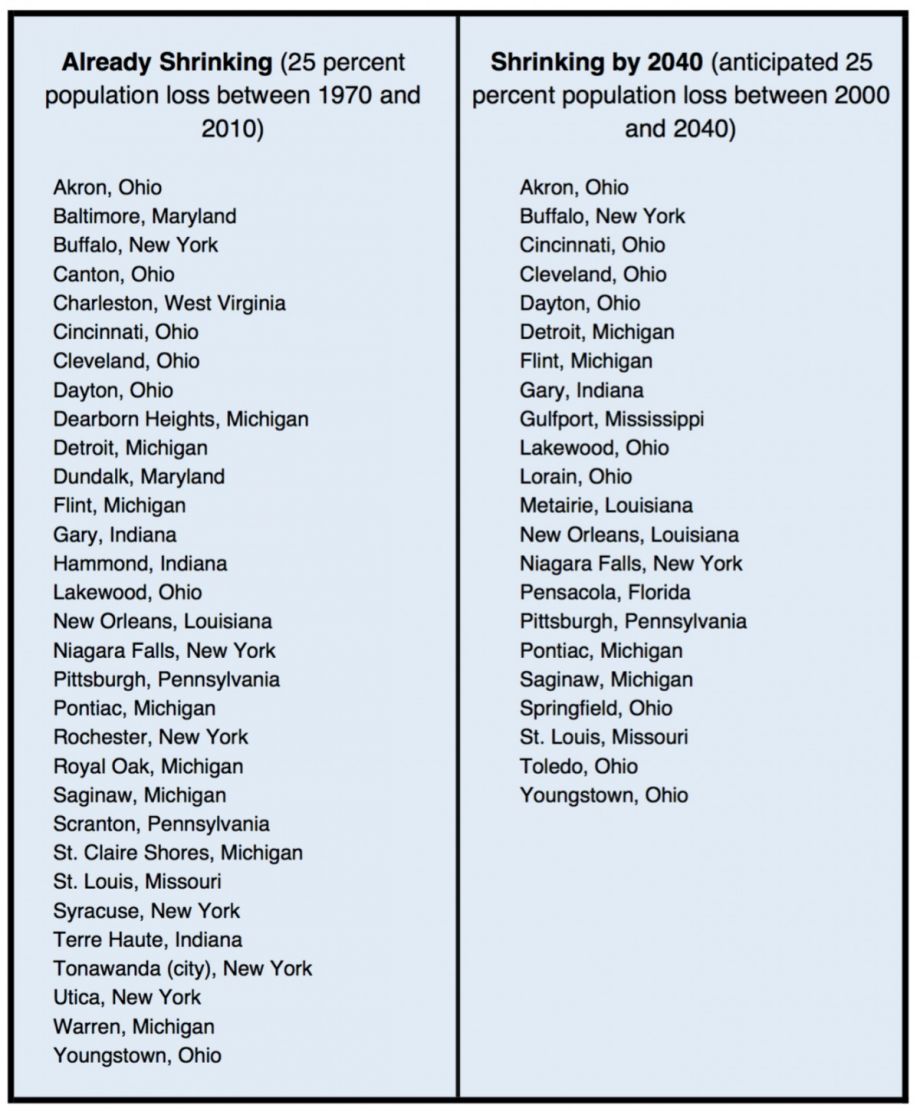

Buffalo, New York. Youngstown, Ohio. And of course, Detroit. Three textbook cases of the shrinking city. Their populations emigrated in droves, generally due to the collapse or outsourcing of a key local industry over recent decades. City planners are still figuring out how to reverse the outflow or at least dull its economic impact on those who’ve stayed behind.

For her new book Shrinking Cities: Understanding Urban Design in the United States, Sharmistha Bagchi-Sen, a geography professor at University at Buffalo, and three other geographers spent two years researching the phenomenon. They combed through census data on population demographics across the country from 1970 to 2010, and hundreds of academic and research sources on American cities in decline.

Two of the book’s key findings: The Rust Belt (particularly Michigan and Ohio) is the epicenter of cities in decline, but it’s not the sole region, as more and more cities west of the Mississippi River report dwindling populations. And the communities who still call these census tracts home were more likely to be impacted by poverty, unemployment and other crippling socioeconomic issues.

On a numbers level, there were 7,386 U.S. census tracts that saw their populations drop by 25 percent over the 40-year census period they examined — a benchmark indicator of a shrinking city. But these areas also saw median per capita incomes drop at an average of $2,334 when adjusted for inflation, confirming the unsurprising correlation that as people flee a city, so goes economic potential.

(List of cities taken from Table 2.3 in Shrinking Cities: Understanding Urban Design in the United States, p. 23)

Census tracts that saw their populations grow, on the other hand, saw an average increase in median per capita income of $1,417.

These were all trends Bagchi-Sen saw on a surface level as she commuted between East Lansing and Detroit. What stood out to her was the way that latter city, which to her was dotted with crumbling neighborhoods as ghostly as a “war zone,” paled in comparison to a perennially booming one like New York.

“When I first came to the U.S. in 1983, the cities were huge contrasts from third world cities,” she says. “They were these great cities with their boulevards and their sky-rises. But then it became clear with others like Detroit and Buffalo, that these cities were just not getting back to where they used to be.”

The book gauges how severe a city is shrinking not just by comparing population levels from year to year but marking some of the key indicators and knock-on effects that come with said decline. On top of shrinking per capita income, that means unemployment, vacant homes, child poverty, lack of access to plumbing — all issues that set the stage for further shrinkage to occur if they’re not addressed with municipal plans of attack, specifically catered to the demographics and circumstance of the city enduring them. A city like Youngstown, Ohio, for example, had upward of 6,000 vacant buildings as recently as 2010.

And while every city council dreams of their metro one day becoming an economic powerhouse, that’s just not always a possibility, says Bagchi-Sen.

“Everyone wants to have a Silicon Valley next door. But then what about the rest of the population? How do we not bypass those who are already there, but also focus on growth?” she says. “We still haven’t been able to bring about the good parts of growth, and understand what the needs are of the remaining population.”

Despite filtering through countless pages of data and research, she says she doesn’t want to be prescriptive; the book was compiled as a picture of the moment, a template to inspire solutions in city planners and other professionals to set the course of city development. But it does highlight a few positive examples of what cities throughout the country are doing to dam their decline, including rightsizing. Detroit, Buffalo and Youngstown are all tweaking the approach — which seeks to modify a city’s infrastructure to fit the current population, not a larger one from days gone by — to fit their own conditions.

Youngstown, an old steel producing city that went from 170,000 people in 1930 to 65,000 today, is considered the godfather of rightsizing, in part because of its blight removal work. The theory is that rehabilitated properties can reinject real estate value back into the neighborhood, with an eye toward improving the quality of life and services for existing residents instead of trying to magnetize others to move in from outside.

To set the stage for this, cities can cut off funding and support to parts of census tracts that have widespread issues with blight, and put that funding instead toward helping the populations that live there relocate to more dense areas of the city. This process, which the authors accurately call controversial, is known as consolidation.

In Buffalo, New York, where Bagchi-Sen lives, city council members attempted a similar plan last decade, calling it Blueprint Buffalo.

One Region Forward, a sustainable development coalition that focuses on the Buffalo Niagara Region, sums up the plan in a way that gives a clear idea of rightsizing in action. “While [Blueprint Buffalo] recognizes the barriers vacancy and blighted properties impose on redevelopment efforts, it also recognizes the opportunities these properties present to the traditional, walkable, and mixed-use communities they are located in,” according to the website. “These include available land at affordable prices, large parcel assembly options for development, room for innovation, potential for a variety of infill, and potential for job generation around skilled workforce.”

Bagchi-Sen and Russell Weaver, another geographer and co-author of the book, researched back in 2013 the decrepit properties in the heart of the city and found that the number and breadth of these properties was growing with every decade. Blight begets more blight, they observed, and one way to stop it may be to uproot the failing properties that sink a neighborhood’s real estate value like an anchor.

That also requires funding and a cohesive government. Some buildings in a housing complex right near one of Buffalo’s prime tourist neighborhoods, Canalside, are buckling, vacant and vandalized, yet the city says it can’t afford to demolish, deconstruct or repair them because of drops in federal funding for affordable housing. Youngstown’s rightsizing manifesto, Youngstown 2010, was drafted in 2002, but a number of funding and municipal shakeups have severely slowed the process. Sean Posey, a journalist who used to work at the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation, paints a picture of what this looked like in a blog post for The Hampton Institute back in 2013.

“The spread of blight accelerates three years after 2010,” he writes. “The poorest and most blighted parts of the city are still predominately black; the most prosperous and stable areas are still white. The city planner’s position is still vacant after five years.”

It’s a startling image of an ideal gone wrong, but city officials do say the rightsizing process is still well under development in Youngstown. And while the jury’s still out on Blueprint Buffalo, Bagchi-Sen hopes her book will help inspire equally innovative approaches to try and reduce this issue as it creeps across the country.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Johnny Magdaleno is a journalist, writer and photographer. His writing and photographs have been published by The Guardian, Al Jazeera, NPR, Newsweek, VICE News, the Huffington Post, the Christian Science Monitor and others. He was the 2016-2017 equitable cities fellow at Next City.