Rushern Baker has been concerned lately about an Indian restaurant, Tiffin, just outside of Washington, D.C., in Maryland’s Prince George’s County. He says it is his two grown daughters’ favorite restaurant.

It also happens to sit along a stretch of University Boulevard where the new Purple Line light-rail system, which broke ground in August, will soon be under construction. When the project is complete, a station will be within walking distance.

As Prince George’s county executive, Baker is concerned that Tiffin could be one of many businesses that may not survive some slim months or years while construction hampers customer access. He’s also concerned those businesses may not be able to afford to stay in the area as light rail spurs a new wave of development — and economic uncertainty. Commercial rents could rise and displace entrepreneurs. A higher cost of living may also force longtime residents out, and newcomers may or may not be interested in the same goods and services offered by current businesses.

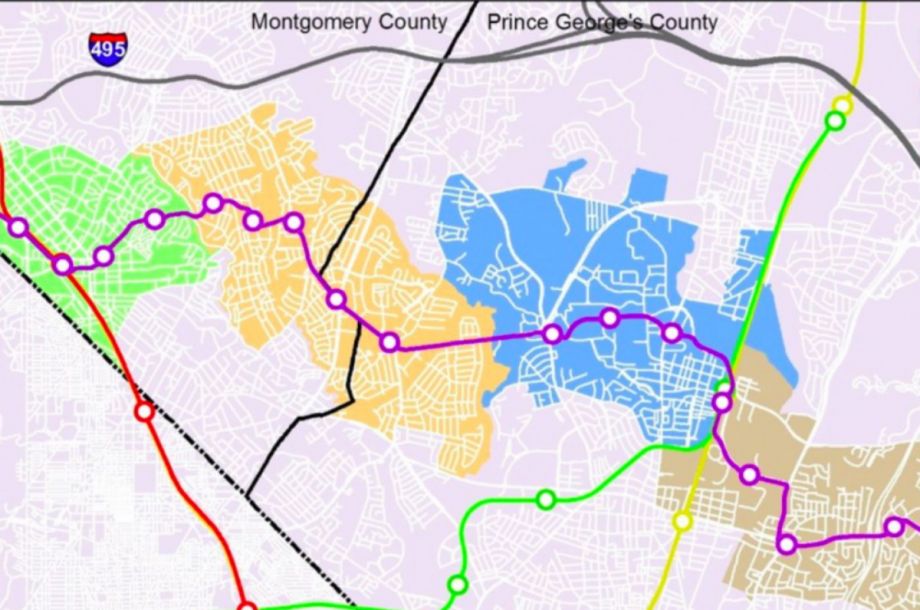

Baker, who’s also making a bid for Maryland governor, isn’t the only one worrying. These concerns are outlined in the new Purple Line Corridor community development agreement, which acknowledges the potential of the light-rail line to create temporary and permanent jobs, fuel economic empowerment, and ease traffic congestion in a crowded region. It covers all of the 16-mile, 21-station Purple Line, between New Carrollton in Prince George’s County, and Bethesda in Montgomery County, and the areas surrounding the transit line.

The document also recognizes the risk of displacing existing low- and middle-income residents and small businesses if preventive policies and programs aren’t put into place in time. It’s a threat Baker knows all too well. Earlier in his public life, after becoming a Maryland state legislator in 1994, he saw what happened to D.C.’s U Street Corridor after WMATA’s Green Line opened (in 1991). Baker says that the benefits touted to people and businesses near a new station were washed away by the wave of incoming development.

“People assumed that naturally the folks that lived around there, the businesses, would benefit from the new wave of foot traffic, people coming into these areas, that they would shop in the stores, that they would buy the houses, and property values would go up,” Baker says. “You really have to be mindful that with redevelopment there is a downside. You’ve got to protect against that.”

The Purple Line Corridor community development agreement is not legally binding, but it pledges the signing parties — which include Baker in his role as county exec, his counterpart in Montgomery County, and the president of the University of Maryland — to pursue and annually review progress toward the goals, strategies, action items and indicators set out in the “Pathways to Opportunity: Purple Line Corridor Action Plan,” developed by residents, government, business, philanthropic, community and academic organizations along the Purple Line Corridor over four years of formal discussions.

The Pathways to Opportunity: Purple Line Corridor Action Plan includes a commitment to a net-zero loss of affordable housing units along the designated Purple Line development area (meaning some affordable units may be lost to market-rate development, but they will be replaced on at least a 1:1 ratio by new affordable housing elsewhere within the corridor). The Purple Line Corridor Coalition, a cross-sectoral group that has been drafting the plan, also did research and established a baseline of 1,900 existing low- to moderate-income rental units with long-term rent restrictions, and another 8,000 low- to moderate-income rental units without long-term rental restrictions within the corridor area.

The coalition members are now embarking on a project-by-project analysis to identify which of these rentals are most at risk of losing affordability in order to prioritize which ones to save first and which ones might have to be replaced with new units elsewhere.

“You may have an owner willing to keep affordability, so what would that take? Or an owner might be interested in selling, so the plan must line up stakeholders necessary to keep affordability in place,” says David Bowers, vice president at Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit affordable housing developer. Bowers’ signature is on the agreement, and Enterprise is taking the lead on housing for the coalition. “Another part of the plan is potentially upgrading units that may be below par in terms of health and safety issues. Another part is to what extent can we get new units, through policy or financing interventions that could increase units of affordable housing.”

Montgomery County became a pioneer of inclusionary zoning back in 1974, when it passed a first-of-its-kind law to require any developer applying for subdivision approval, site plan approval, or building permits for construction of 50 or more dwelling units at one location to ensure that 15 percent of the units were “moderately-priced dwelling units (MPDUs).” In exchange, the county offered density bonuses of up to 20 percent, allowing for a greater number of units than zoning permitted.

That law has never been challenged in court. It currently requires that between 12.5 percent and 15 percent of homes in new developments of 20 units or more be moderately priced. Currently, the program also requires that 40 percent of them first be offered for sale to the Housing Opportunities Commission, Montgomery County’s public housing agency, and to nonprofit housing providers.

Prince George’s County, meanwhile, does not have such a law. It is also the only jurisdiction in the D.C. area without an active housing trust fund, a pool of money created out of dedicated public funding streams in order to preserve and construct affordable housing.

When it comes to businesses like Tiffin, as the Purple Line project progresses, Baker hopes to help local entrepreneurs apply for money that will aid them in weathering construction headaches and overall development. Prince George’s County has a $50 million economic development incentive fund. That gets distributed in annual chunks of $7 million to $11 million, and provides loans and sometimes grants directly to businesses for building acquisitions, building construction and improvement, equipment acquisition, and working capital.

Baker also foresees additional legislation to expand or continue funding for businesses, low- and moderate-income renters, homeowners, job seekers and other potential beneficiaries of the corridor.

With accountability and transparency in mind, the coalition has established a data dashboard, for current and future data and reporting on the implementation and impact of the Purple Line Corridor Action Plan, including its net-zero affordable housing loss commitment. The National Center for Smart Growth, based at the University of Maryland and also a signatory to the agreement, posted a series of maps that capture the state of the corridor and surrounding areas at the outset of construction.

While these tools are helpful, Baker acknowledges that it will fall on others to take the data and hold officials accountable through the ballot box if necessary.

“The price of liberty is eternal vigilance,” Baker says. “Everybody coming after us in these local positions is running on something. Remind them of the moral compact created here.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)