Is there anyone out there today who doesn’t agree that the individual or the community in any given place should have a voice in how that place gets used? Bigger institutions play a role, but the primacy of “the little guy” when it comes to economic development might be the closest thing to a universal truth recognized by all city-dwellers, urbanists and leaders. But just like so many things hailed as universal truths, it’s forgotten as much as it is celebrated.

NYU professor and economist William Easterly has been seeking to tell that story for a long time. With the recent launch of the Greene Street Project, an interactive online exhibit, he and his collaborators made quite a stab at it.

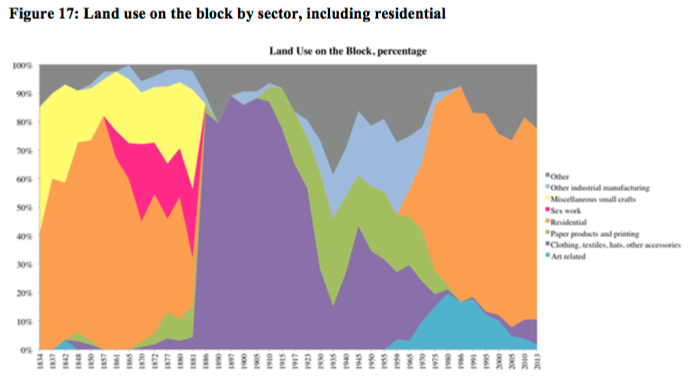

First, they combed through historical records, journal entries, land use documents, official and unofficial land surveys, census data and more, spanning about 400 years starting from the 1640s. (There’s a working paper too.) To keep all of that manageable, and relatable, they (somewhat arbitrarily) chose to focus on the perspective of a single city block: Greene Street, between Houston and Prince streets, in NYC’s chic SoHo neighborhood.

Studying just one block also allowed for the primacy of the little guys to shine through — and revealed a slice of economic development history that urban planners, amid their attempts to predict and shape the future, might want to check out.

“I think we helped dramatize which kinds of urban planning are a disaster and which kinds are helpful and good,” Easterly says. “The ones that are a disaster are the ones that try to prescribe exactly what sector should be operating on which block or which neighborhood, or try to directly reverse the decline of one industry that’s operating in a neighborhood.” (He has written two contrarian books that have made waves in global development: The White Man’s Burden is about the harm caused by wealthy Western nations giving large amounts of aid to poor countries. Tyranny of Experts takes down the over-reliance on technocrats by global development leaders, from the World Bank, where Easterly worked in the 1990s, to Bill Gates.)

In other words, if you are a mayor or other local government agency that has been reaching out to specific industries and trying to get them to grow in a specific place, you are doing economic development wrong, according to Easterly.

Of course, there are more than a few promising examples of local governments reaching out to specific sectors of local businesses to do just that. There’s up-and-coming Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson pushing for an artist-inspired restaurant incubator to help spark downtown-style re-development in Gary, Indiana (recently featured on Next City). There’s also Pittsburgh’s inclusive innovation roadmap, which, while not tied to any specific location, does consist in large part of the local government coordinating more closely with local industries on mutually identified policy and infrastructure priorities.

But Easterly argues that government should focus on creating and maintaining the things that people — no matter who is living or working on any given block — will need. Basic infrastructure, education systems, public health, mass transit, for instance.

A prime example in Greene Street’s history is a period in which brothels started to pop up on the block, in order to serve the early entertainment district emerging on Broadway in the 1850s. It led many existing residents, some of whom were quite wealthy, to move farther uptown (north). That cleared the way for the garment industry to come in during the 1880s, tearing everything down and building up the glorious cast-iron buildings that characterize SoHo to this day. It was simply too convenient a location for the garment factory owners to pass up, Easterly says. It was close to the piers where they brought in cotton and shipped out final goods, and walkable to where their nearly exclusively immigrant workforce lived.

No one could have predicted those changes. And that’s largely the point.

“What we find on our block is it’s just one surprise after another that nobody could have predicted. Just letting the surprises happen is much better than trying to say ‘I want the garment industry to thrive on this block.’ The planner cannot say that,” Easterly says. “Any attempt to make that happen will backfire and make things worse. That’s really what we learn from our block.”

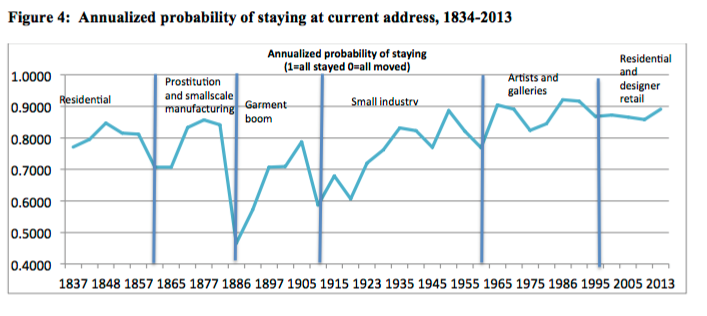

That unpredictable nature of economic development, Easterly says, is exactly what creates the space for new or once marginalized populations to come in and start shaping their share of the future. On average about an eighth of the residents on the block have been turning over every year. That’s not an unusual number in a city, Easterly says, and they show it over almost 200 years for which that data is available.

“It’s part of the dynamism of cities,” Easterly explains. “You don’t want to freeze any existing set of residents in place, you want to let them naturally gravitate toward new opportunities or you want other new opportunities to gravitate to that block that might buy them out for a fair price and set them up to do what they want to do somewhere else in the city.”

For the same reason, most of affordable housing policy today is also getting it wrong, according to Easterly.

“I’m very much on board with the issue of helping poor people, but I think you should help poor people rather than places,” he says. He thinks people should have a living wage or a public subsidy to help them have an adequate living environment, but not tied to a specific place.

“Large districts of public housing basically become prisons for poor people because you’re giving them a benefit that forces them to stay there,” Easterly says. “You’re taking away from them the dynamism that everybody else has access to, to move anywhere in the city they want to find their best match with their current skill set with whatever is going on in different parts of the city.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)