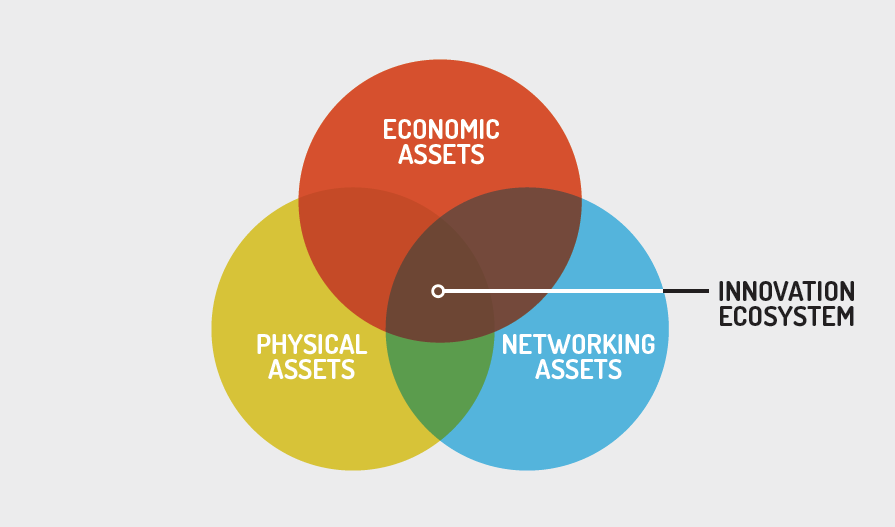

The “innovation district” is still being defined, says Brookings Institution vice-president Bruce Katz, but such a place can be spotted by looking for three things: 1) a hyper-concentration of players in the innovation economy, from big, institutional R&D labs to tiny start-ups; 2) the markers of so-called smart urbanism, like robust transit options, mixed-use real estate and walkability; and 3) a regular colliding of people with a range of talents and expertise.

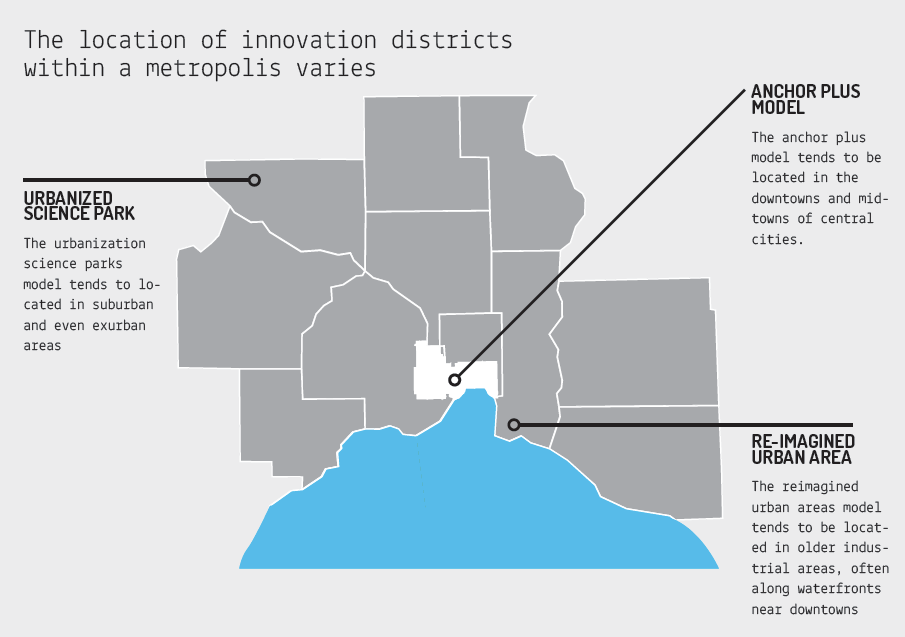

A brand-new Brookings report, “The Rise of Innovation Districts: A New Geography of Innovation in America,” which Katz co-authored with Brookings fellow Julie Wagner, offers that, “In contrast to suburban corridors of isolated corporate campuses, innovation districts combine research institutions, innovative firms and business incubators with the benefits of urban living.”

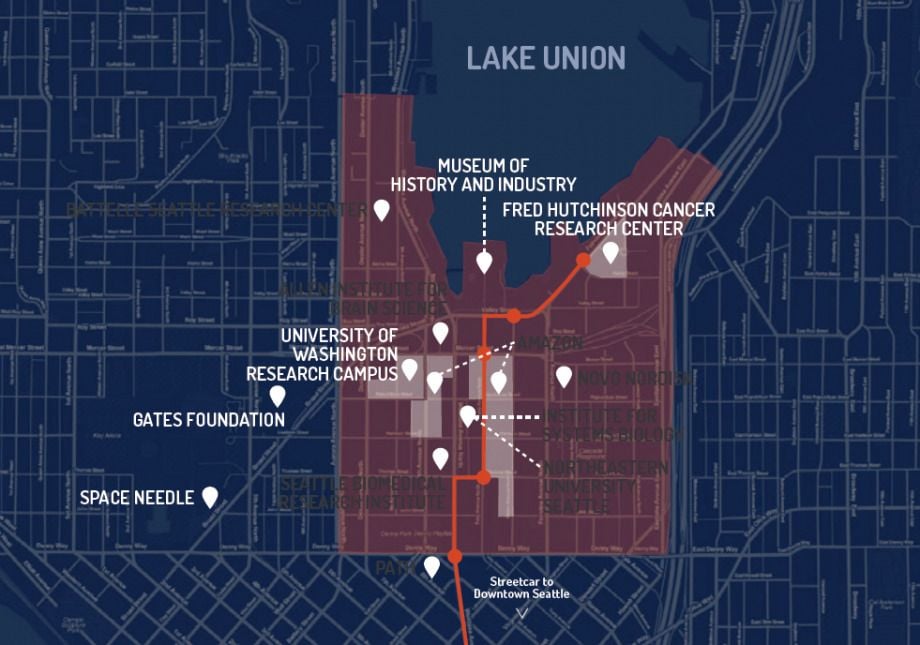

South Lake Union (SLU) in Seattle is one of the report’s dramatic urban transformation stories. A rundown warehouse district a mere decade ago, SLU is now a vibrant, mixed-use engine of housing, transit, and global technology and life-science firms.

Vulcan Real Estate, a company owned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, spearheaded the transformation. In the aftermath of a failed referendum to approve a public park, Vulcan began to assemble distressed properties in the area. In the early 2000s, it persuaded the University of Washington to locate its medical and bioscience campus in SLU. UW and the existing Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center fueled the growth of healthcare and life-science firms. In the late 2000s, Amazon decided to locate its global headquarters in SLU, accelerating growth in not only housing and retail but also entrepreneurial businesses.

The growth of SLU has been marked by a close public-private partnership — including key public investments to build transit, fix congestion and enhance energy — as well as extensive engagement of local neighborhoods and residents. Growth has been iterative and incremental and built on trust and collaboration.

In advance of the report’s release, I spoke with Katz about everything from the role of city mayors in innovation districts to why cities exist.

The report touches on everything from tech companies to coffee shops to the sort of density that lends itself to the sharing of ideas. And there’s also a quote from MIT researchers that adds the notion that they are messy, with activities and uses all mixed up and things in a constant state of adjustment and change. I found myself wondering, isn’t this just what we used to think of as a good city?

From a place-making perspective, we’re celebrating what makes cities so distinctive not just in the U.S. but all over the world — density, proximity, old and new, architecture and design. But for our country, which has been through 20 years of “new urbanism” and transit-oriented development, we’re really stressing the innovation side of cities, and the notion that what is happening in these districts is really part of the advanced economy.

They’re making products and providing services that are ultimately going to be traded beyond the city limits. For a long time, city builders have focused on the consumption side of cities — the coffee bars, the retail establishments. We’re trying to get back to recognizing the raison d‘être of cities, which is being at the vanguard of market innovation. This is why city-ness exists, quite frankly.

You and Julie write about how many on-the-ground practitioners cite the instrumental role mayors can play in catalyzing the formation and evolution of innovation districts, especially in the United States. If a city doesn’t have an innovation-minded mayor, is it out of luck?

The mayors can play that role on the public side; they do have land use and zoning and other powers that really matter. [Then-Mayor Tom] Menino was clearly the driving force in Boston’s seaport. But this is not solely about mayors. In South Lake Union, it’s Vulcan Real Estate, working closely with the mayor. In San Francisco, in the Hunters Point Shipyard, it’s Lennar Urban.

At the end of the day, what you need is a collaborative leadership network, with one entity or one individual that is the driving force to get stuff done.

But once something catches on as one of these innovation districts, doesn’t it start to become hugely attractive to other companies and other people who have little to do with innovation? I look at a place like DUMBO in Brooklyn, and it’s gotten so popular that there doesn’t seem to be much room left. How do you prevent the area from losing whatever unifying characteristics it might have?

I’d differentiate between districts that congregate around motherships and those that are entrepreneurial led, start-up led.

The first have advanced research, medical or even corporate R&D as their base. Nothing is permanent, but there is a solidity to that. Think about Carnegie Mellon, MIT or Georgia Tech. They’re not going to pick up their large campuses and move. But the DUMBO situation probably takes a lot more deliberateness to maintain over time, especially when market rates are going to rise. You see this already happening around the country. There’s a price dynamic that occurs relatively early in the life of these districts.

And that’s why the place-making and network-building is a key part. It’s not just enough to have your economic assets. You really have to focus on the place and programing programming side so, in the end, companies either have to be there or very close to it. That begins to counter the price effect, because there’s something special about geographic concentration, particularly when it’s reinforced by smart place-making, transit connectivity and the programming of these collaborative spaces. People are hungry for that.

So much of what’s promoted about innovation districts is the idea that people are going to run into each other crossing the street or at the coffee shop and solve some of the world’s major problems. But that opportunity seems to be, as you write, highly localized. In fact, you cite staffers at Harvard Medical School who say that while it seems to help to work in the very same building, otherwise, it’s really out of sight, out of mind. Has anyone really been able to figure out how to usefully mix on a broader scale?

There’s really a sort of choreography of collisions. You know it when you see it, and you see it in Eindhoven in Holland. You see it around the Cambridge Innovation Center. You see it in Cortex in St. Louis. It’s about the interplay of designed spaces — both the space within the building and the space in the public realm — and programming that allows for the constant interaction. And that’s evolving … and it’s constantly being impacted by technological advances.

But there, is, in the end, something about building a place that has as its core a sense of urgency, vibrancy, serendipity and spontaneity. It’s sort of odd in a way, because so much of that is [normally] organic. But this is why you want to have architects and designers and interior designers — a mix of disciplines — that begin to converge around the buildings and broader environment.

But, yes, there are some places, either because the entrepreneurial culture isn’t quite as strong or the density effect isn’t quite as large, that think they’re getting it, but they’re not quite getting it yet.

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.