Or, for that matter, without Facebook, texting and cell phones? Edith Lee-Payne was 12 years old when she was captured in an iconic photo of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, holding a pennant that reads “I Was There,” and a sketch of the Lincoln Memorial. She tried to capture the moment for a young crowd gathered at a 50th anniversary youth mentoring summit held yesterday at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.

“Think about this,” Lee-Payne said. “Fifty years ago, we didn’t have social networking; 250,000 [people] had only telephones and party lines. But they came.”

And they came to Washington, D.C., a city of 800,000 residents in 1963, to claim the physical spaces of the nation’s capital for themselves. “We propose,” the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins is recorded as saying during the rally’s contentious planning process, “to use the capital as a parade ground for human rights.”

Only in retrospect has it really become clear to the broader world just how much work that took, and how much the 1963 March on Washington was more than a triumph of the Civil Rights movement. It was also a master class in field organizing and social geography.

At the center of it all was Bayard Rustin, a sometimes-controversial Civil Rights leader (he was gay, for one thing, and this was the ’60s) whose name is on the “Final Plans for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” a 12-page organizing manual dug up from Tulane University’s Digital Library by Slate’s Rebecca Onion.

“The March on Washington,” it reads, “projects a new concept of lobbying.” The various groups and actors who made up the Civil Rights movement had tried meetings with members of Congress, and petitions and policy papers with presidents. “Instead,” with the March, “we have invited every single Congressman and Senator to come to us.” (Emphasis in original.) Seats would be reserved for those politicians down at the Lincoln Memorial.

“Our time is short,” reads the guide. “MAKE THE MARCH KNOWN.” Supporters were encouraged to issue press releases, write letters to the editor, and order and distribute more copies of the organizing manual. “Your primary task is getting people to Washington.”

From there, the organizers dive into logistics. Local leaders are given instructions on how to go about reserving a bus and reviewing its contract. “Do not pay extra for parking facilities,” they’re warned. Those will be provided for in Washington by the national office. Trains are good for large groups, and they make it easy for people to communicate. Private vehicles are discouraged, though if would be marchers insist on taking them, “make signs reading MARCH ON WASHINGTON and place these on their cars.”

To handle the arrangements, local organizers were to set up transportation committees and “appoint a hardworking person as its chair.” On buses, seats would be reserved for the unemployed, at a ratio of at least one to every three marchers paying their own way. The last page of the booklet is a “Transportation Report Form,” for bubbling up the plans made in Detroit and Houston and Los Angeles to national organizers.

The guide also covers more personal details. “Be kind to your stomach,” marchers are warned. Pack two box meals, but “no mayonnaise.” Marchers would only need two because they needed to leave the city as soon as the March was over. There would be shuttles back to buses, cars and trains. “The size and scope of this March make it imperative that all participants come and go out on the same day.”

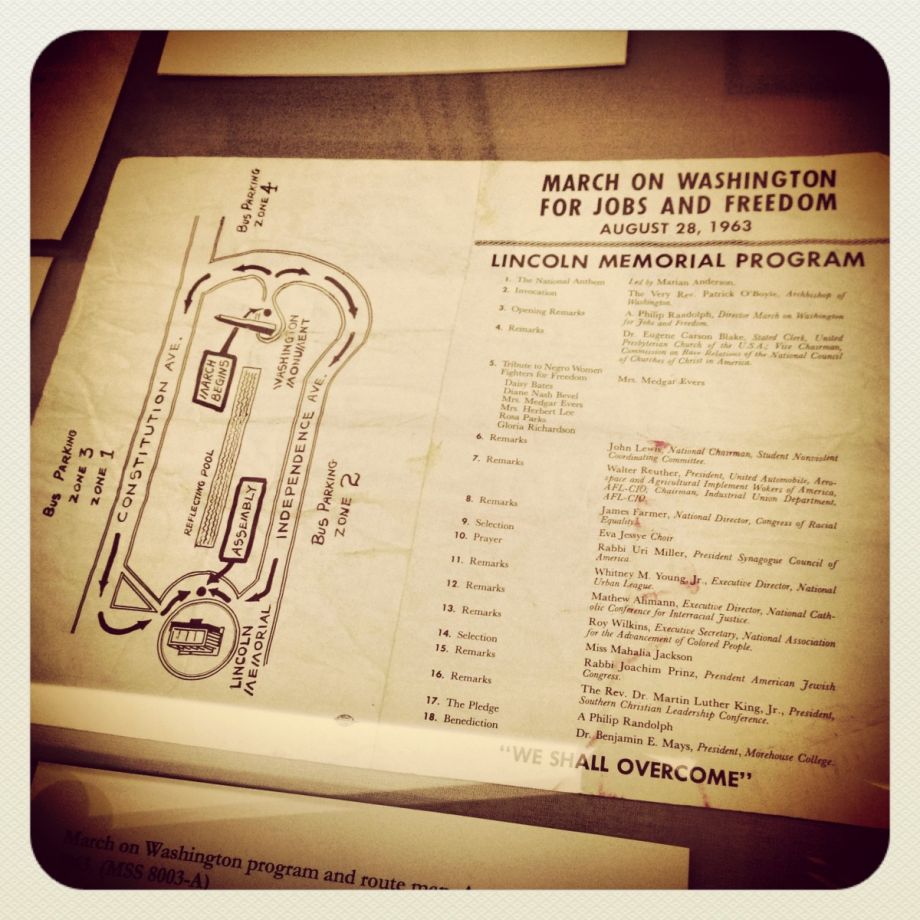

As for the geography of the march itself, this second edition of the guide had two updates over the first. In a bid to speak with their own voice, the authors were scrapping the idea of designating state-specific gathering points. “Your destination is the Washington Monument,” and they should be there by 10 a.m. Events at the Lincoln Memorial — including what would come to be Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s historic “I Have a Dream” speech — would begin at noon. But the parade route had been switched. “The NEW routes of March are Independence and Constitution Avenues.”

Why the change? We get the backstory from Lucy G. Barber’s 2004 book, Marching on Washington: The Forging of an American Political Tradition.

Rustin, Barber writes, “had long made planning demonstrations his vocation.” In the days leading up to the march, he put together the “first mass-marketed protest in the history of demonstrations in Washington,” making use of buttons, fliers, press hits, concerts and more to drum up attendees. His Harlem planning office in particular served as one big advertisement. His judgment, writes Barber, was to make use of “the political space of Washington” by protesting near Capitol Hill and the White House.

But negotiations between organizers and permanent Washington changed plans, shrinking down the rally to its new, less provocative route. Organizers had been working with a President Kennedy eager to prevent damage to his Civil Rights legislation. “The shared investment in designing an acceptable march showed,” Barber writes, “as the Kennedy administration’s assistance went beyond just security planning to actively assisting the organizers to ensure that the marchers were comfortable and the march went as planned.” One result of that cooperation was that “the protest that had earlier threatened most of the official symbols of federal authority would now challenge that authority from their own distinct space on the Mall.”

It’s true that by 1963, Barber reports, marching on Washington had become “a national habit,” as a local police official put it. There were those against segregation in the District of Columbia, one on occasion of the executions of the spies Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. But the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was something different. In Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63, historian Taylor Branch details how Washington, D.C. halted the sale of liquor “for the first time since prohibition.” Store owners moved their stock to remote warehouses over fears of looting. The Washington Senators baseball team postponed games until it was all over.

Expectations that the March on Washington would turn violent helps explain Bayard Rustin’s fixation on the day’s logistics. “He drove his core staff of two hundred volunteers to pepper the Mall with several hundred portable toilets, twenty-one temporary drinking fountains, twenty-four first-aid stations, and even a check-cashing facility,” Branch writes. One of his preparations involved posting signs with words of guidance high above the crowd, the place where a march might glance in a moment of frustration.

Barber tells us how it all played out:

On August 28, 1963, marchers traveling to Washington could see the enormity of their effort. Whether they came in single buses from small towns or in the grand caravan of 45o buses that left New York from Harlem, marchers rode to Washington alongside other buses and carloads of marchers. By midmorning, buses were passing through the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel at the rate of loo an hour. Those arriving on trains also sensed the enormous turnout. Marchers on trains from the North, from cities like Boston and Philadelphia, from the West, such as from Cincinnati and Chicago, and from the South, including from Jacksonville and Birmingham, all emptied into the vast space of Union Station and then moved off toward the Mall. Long before the scheduled 1:30 start, people covered the hill around the Washington Monument. By the end of the day, nearly a quarter of a million people had come to the capital, setting a new record for marches on Washington.

All these marchers combined to take over the core of the capital and made its spaces into their own.

Branch writes that Rustin, the March’s lead organizer, had a saying he used often: “If you want to organize anything, assume that everyone is absolutely stupid. And assume yourself that you’re stupid.” Smart.

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.