Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberIf everything goes on schedule, sometime next August flatbed trucks will haul the first of some 930 modular units from a fabrication facility at the Brooklyn Navy Yard to a staging area next door to the Barclays Center, Brooklyn’s new 19,000-seat arena. Along the two-mile drive, the units — steel-encased fragments of a skyscraper with pre-installed plumbing, wiring and insulation — will pass the Raymond V. Ingersoll housing project, which sits in the second poorest census tract in Brooklyn. Then, after a left on Flatbush Avenue, they will cut through New York’s largest business district outside Manhattan and cruise down a corridor newly adorned with luxury high-rises (like the oscillating glass- and aluminum-paneled Toren and the borough’s tallest building, the equally luxurious Brooklyner).

At Dean Street, cranes will lift each module, some as long as 50 feet across, and attach them together, creating B2. When finished, it will be the tallest modular building in the world and the first residential part of the contentious Brooklyn megaproject, Atlantic Yards.

One of these modules will presumably belong to Kassoum Fofana.

When we spoke in November, Fofana hadn’t yet been to the Barclays Center to see the Brooklyn Nets. In fact, he said he preferred the Chelsea Football Club to the newly relocated basketball team. For someone who will soon have a home in the arena’s backyard, it’s perhaps surprising. But Fofana, 48, straddles both sides of Atlantic Yards history.

Fofana, a carpenter, moved to Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood from Burkina Faso in 1995 and eventually brought his wife, son and daughter to live with him. Late one night in February 2006, an arsonist set fire to his apartment building. As the rooms filled with smoke, he lost track of his family and jumped from the third floor to the sidewalk, where the body of another victim broke his fall.

Later in the hospital, he learned that his wife, Assita Coulibaly, and kids, Miriam, 3, and Mohammed, 1, were dead. “It was painful,” he said, sitting in a Bedford-Stuyvesant Internet café and print shop run by a friend. “All the time I think about my family. It was difficult.” (Police caught the alleged arsonist last year.)

Fofana also lost his livelihood. With extensive damage to his hands, back and knees, Fofana, who specialized in cabinets and furniture, couldn’t work. With his life shattered, help came from an unexpected, if well known, source. At the funeral for Fofana’s wife, the carpenter’s nephew met James Caldwell, a longtime civic activist, then working for a new non-profit, Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development, or BUILD.

Funded by Atlantic Yards developer Forest City Ratner, BUILD had been formed two years earlier to connect Brooklyn residents to job opportunities created by the project. Caldwell told Forest City Ratner CEO Bruce Ratner about Fofana’s situation.

“Without any hesitation, [Ratner] put [Fofana] in one of the houses that they had bought from one of the other families for $1 million,” Caldwell said. “They put him up there, rent free. Our organization went out and bought him some pots and pans, sheets and pillows, and stuff of that nature.”

Fofana stayed with his son, nephew and sister for two years at an apartment across the street from where the Barclays Center now sits. Ratner, who planned to turn the site into a small parking lot for arena-goers, had recently bought the building and evicted its tenants. When the time came for demolition, Fofana moved deeper into Bedford-Stuyvesant, taking up in the modest duplex where he now resides. The market rent there is $2,100, but Fofana’s rent is capped at $600 — a deal resembling that given to the demolished building’s other tenants who agreed to move away and get their rents capped at former prices. In total, 181 of the rentals in the 363-unit complex will have rents capped at below-market rates in exchange for $92 million from the city in tax-exempt bonds.

Fofana doesn’t know yet which floor of the 32-story, 322-foot building will be his when B2 opens in 2014. But no matter what, his windows will look out at a dramatically different Brooklyn than the one he moved to in 1995.

“Without any hesitation, Ratner put Fofana in one of the houses that they had bought from one of the other families for $1 million.”

It’s been a long two decades for Brooklyn. Inside of a generation, entire neighborhoods of New York’s most populous borough have become unrecognizably chic. Much of this change happened gradually, but the 10-year period since Ratner announced his $4.9 billion megaproject has been a whirlwind of development, gentrification and displacement.

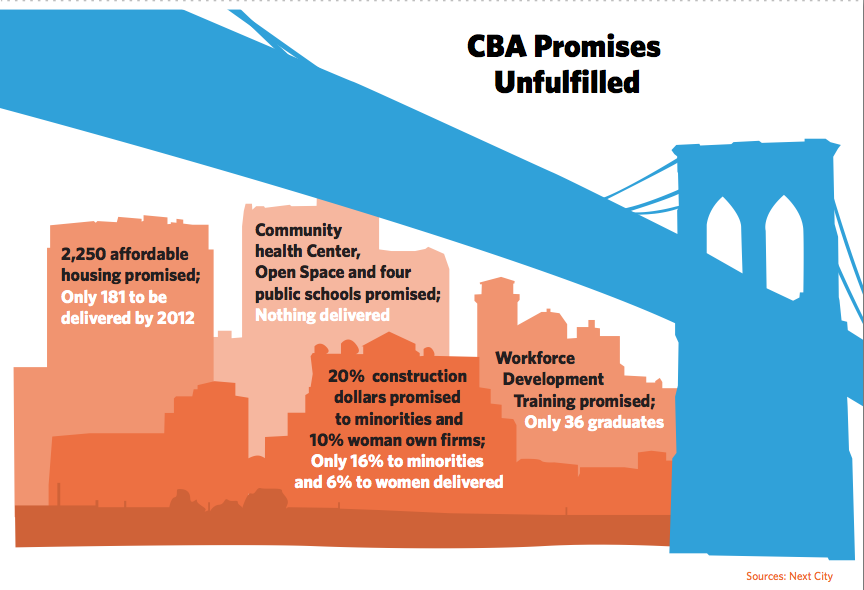

At the center of all of it all has been Atlantic Yards. Spread over what were six blocks, Ratner’s plan will put 16 high-rises beside the billowy, rusted-red arena. Beyond more than 6,400 residential units, 2,250 of which will be reserved for more middle-class families, there are plans for offices, a charter school and eight acres of open space. Also planned is nearly 250,000 square feet of retail, nearly two-thirds the size of Atlantic Terminal Mall, another Forest City property, across the street.

When Atlantic Yards reaches full build-out, it will rival any New York City project outside Manhattan in scale.

Accordingly, larger-than-life characters dominated headlines after Ratner, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz unveiled plans for the gambit. Among them are rapper and Nets part owner Jay-Z, six-foot-eight Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov and starchitect Frank Gehry, who designed the early models of the arena.

But another story of the project’s success is what it means for the community that it pledged to transform with new jobs and economic activity. By a random stroke of politically tinged fortune, Atlantic Yards provided Kassoum Fofana with a home in Brooklyn, allowing him to stay in a part of the city he may have otherwise had difficulty affording. But the troubling fact remains that as taxpayers dedicate billions of dollars to subsidizing projects, there are no guarantees that benefits will flow to others in need.

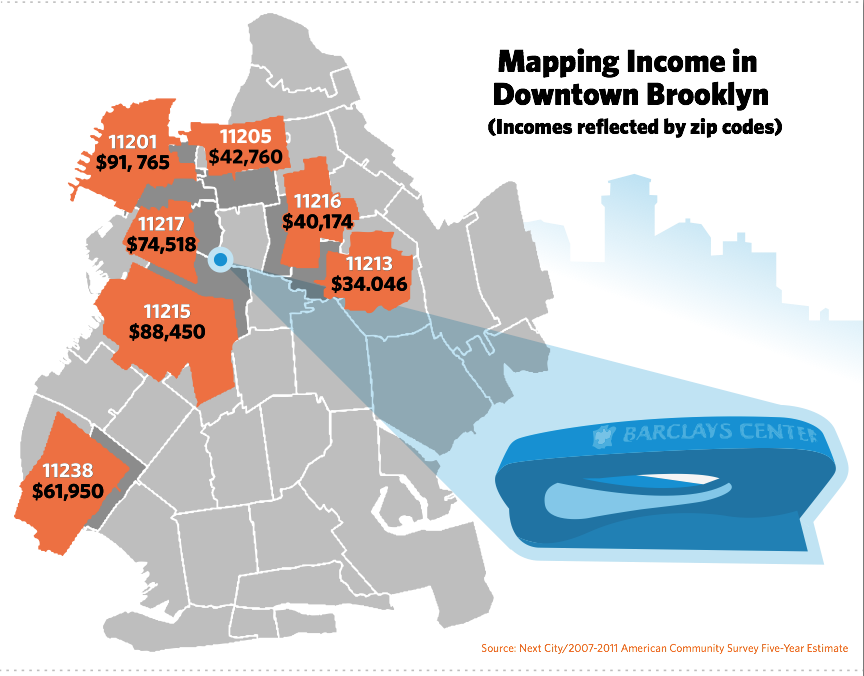

Atlantic Yards sits blocks in either direction from well-to-do brownstone belts, low-income housing projects and the density of Downtown Brooklyn’s business and retail corridor. Accordingly, economic differences are just as stark. Median incomes in Park Slope routinely top $100,000, but only reach $9,650 in the nearby census tract that includes the Ingersoll and Walt Whitman housing projects, making them the second poorest in New York. Gentrification has redefined the neighborhoods as well. While an artisanal mayonnaise store opened last year blocks away from the Barclays Center, people in Brooklyn receiving income support rose five percentage points from 2005 to 2011. These historically black neighborhoods are also getting whiter, as longtime residents flee for East New York, Canarsie or even other states.

It was in this environment that, in the summer of 2005, Bloomberg and Ratner stood at a park near the Brooklyn Bridge to announce the creation of a community benefits agreement (CBA), the first of its kind in New York. With them were leaders of eight community-based groups who signed the 73-page document that promised affordable housing, local hiring and community programs. In many cases, the groups gave institutional blessing in exchange for operating funds.

Dating from the late 1990s, CBAs are a popular instrument in the urbanist tool belt, helping to negotiate benefits for the communities directly affected by a development. “Covering a lot of issues and having a lot of groups sign it is what lets the CBA have credibility as having addressed the most important issues to the community,” said Julian Gross, a California-based lawyer, who has helped negotiate at least a dozen agreements.

CBAs have been used in all sorts of purposes, such as a $2.8 billion light rail project in Atlanta, a cancer research center in New Haven, Conn. and a casino in Philadelphia. But for many observers, the model CBA came from a 2001 mixed-use expansion near the Staples Center in Los Angeles. Deals within the agreement, signed by a coalition of more than 30 groups and unions, included $100,000 in seed money for workforce development programs, $650,000 interest-free loans for non-profit housing, $1 million for nearby parks, living wage guarantees and more. So far, it’s largely been regarded as a success.

James Caldwell signed the Community Benefits Agreement on behalf of his workforce training organization, BUILD. The non-profit has since folded, and people it trained have filed a lawsuit against the organization.

The high-profile Brooklyn CBA laid the groundwork for the city and state’s support of the project, which amounted to about $300 million, not including tax exemptions.

The CBA’s boosters often compare it to the Staples Center agreement, but there are indicators that it will yield a different result. One stark comparison can be made looking at the groups of signatories and the operations they ran. Seven years after the Brooklyn document was signed, five of the groups have been mostly silent or reconstituted after without much fanfare.

BUILD, which closed in November, can be seen as a symbol of the CBA’s role so far. It graduated 36 apprentices in a construction program, but in November 2011 seven of them sued the organization, as well as Caldwell and the developer. The apprentices alleged a bait-and-switch, claiming they worked for free for two months to build a Staten Island house in exchange for union cards that never appeared. According to the complaint, no Barclays construction jobs were offered to the group, which included experienced carpenters and electricians living in Brooklyn. Instead they were offered temporary political canvassing or retail jobs, paying a fraction of the construction jobs.

Since the seven plaintiffs initially filed the suit, about a dozen more apprentices have joined it, according to Matthew Brinckerhoff, an attorney at a Manhattan-based law firm helping to represent the case. He expects the next phase could come later in the year. (Caldwell has asserted that BUILD guaranteed job interviews, but jobs were never promised to anyone in the program.)

The other groups remain operational but have few solid achievements beyond memories of Ratner-funded summer camps, air conditioning units, ball games or concerts. These charitably acts are certainly kind gestures, but they haven’t added up to the structural or systemic cooperation that happens in L.A. or other cities with CBAs.

“These people provided cover for Forest City Ratner to suspend all zoning, and then they go back on their word and now they just go away,” said Jim Vogel, a spokesman for Brooklyn State Sen. Velmanette Montgomery. “They got their arena.”

In 2010, a task force led by the city comptroller studied CBAs in New York and noted that similar agreements — signed when building the new Yankee Stadium, a retail complex in the Bronx and Columbia University’s Manhattanville expansions — “were negotiated in a context where no clear and generally accepted standards existed, which allowed critics of the projects to question their credibility.”

Tom Angotti, an urban planning professor at Hunter College, was a member of that task force. “It considered different opinions and different views of community benefit agreements,” he said. “But I think the majority of [the task force] agreed that in New York City, [CBAs] have been hijacked by developers and by pro-development advocates.”

“From the developer’s point of view,” he said, “it’s a good tactic for minimalizing opposition and opening the way for minor concessions: Buying off opposition or buying off sectors of the community by throwing around some free tickets to a Jay-Z concert, or whatever.”

It was a cold December day and a few hundred people sat under a white tent to witness the mayor and the developer herald the long-awaited groundbreaking of B2. Sitting close to Bloomberg and Ratner were project supporter Bertha Lewis, the former head of ACORN, and Gary LaBarbera, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York. LaBarbera is a key part of the agreement to hire union members for the modular effort. Smiling in the direction of the two beaming billionaires, he praised the agreement.

“We saw that without that modular construction that these projects would more than likely not go forward,” he said.

With the switch to modular construction, the New York Times reported that transitioning most of the work at the Navy Yard would save 20 percent on costs, including 25 percent less on labor. Though there’s been some consternation from within the building trades, who will bear the wage cuts likely to come with modular construction, unions remain cautiously hopeful about the next phase of the project.

“If they could put up something that’s decent, that’s livable, you know, maybe that’s the way to go,” said Richard O’Kane, a business manager at Ironworkers Local 361, a 1,100-member union whose workers put up the Barclays Center. “But it does eliminate jobs that people were used to doing in the past, and it’s hard to replace those jobs as people were doing them.”

“We have to progress with the times,” O’Kane said, “whether it is conventional or modular construction.”

Rev. Herbert Daughtry officiated a random sweepstakes that decided who would get free community tickets to Jay-Z’s inaugural concert at the Barclays Center. The free tickets were negotiated as part of the Community Benefits Agreement.

The internal scuffle comes after a long line of disappointments. In the big picture, jobs haven’t appeared in the numbers promised by officials — who, when selling the project at first, predicted nearly 17,000 construction jobs and 8,000 permanent jobs. As recently as 2009, the Empire State Development Corporation, a state authority charged with managing the project, predicted 4,538 new jobs in the city. (Because much of the project was on state-owned land, the city allowed Albany to rule on Atlantic Yards.)

But during the work, the average workforce at the site ranged from 841 (as Forest City spokesman Joe DePlasco told the New York Times when the arena opened in September) to 880, which the developer reported in late July. According to the developer’s figures, when the average was 880 construction jobs, 256 were Brooklyn residents and less than 10 percent were from the four community boards in the area. There are around 2,000 of the more permanent arena jobs, but only an estimated 105 are full time.

(“We have met our construction and arena hiring numbers and anticipate we will continue to do so,” DePlasco said in an email.)

Other benefits did materialize. “I can’t speak for everybody else, but we had a convergence of interest,” said Rev. Herbert Daughtry, founder of the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance, which receives ongoing funding from Forest City. “We were both concerned about how we could maximize our benefits to the community. And at the same time, obviously [Ratner] is a businessman. He wanted to be able to make some profit to expand the business and to do more good things.”

Daughtry’s organization negotiated health-related programs and a patchwork of arena-related perks, including 54 arena seats, a suite, a “meditation room” and 10 free events through the year. Through a random sweepstakes, the winners of the first giveaway went to Jay-Z’s inaugural concert.

“It took a long time to devise a system that would be fair and open,” Daughtry said the week of the Barclays opening. “Originally people were saying we were only going to do this for our friends, cronies and family, so we developed a system that at the same time would prioritize the people that are least likely to be able to purchase a ticket to these events.”

Daughtry has been eager to talk about how his community has benefitted from the CBA, though some are less so.

Charlene Nimmons, a resident association leader at a housing project half a mile southwest of Atlantic Yards, heads a small non-profit called Public Housing Communities, created to connect public housing residents with jobs. Its role in the CBA was to ensure public housing residents were included in every aspect of Atlantic Yards. The agreement stipulated that Forest City would help fund — directly or indirectly — the organization and three full-time employees. According to the 2007 and 2008 tax forms, the most recent years available, PHC got a total of about $450,000 in grants from unspecified donors. In both years, its biggest expense was salaries, about $86,000 each year, and “donated facilities.” Reached by phone, she (perhaps characteristically) declined to comment on the progress. Asked about PHC’s role within the New York City Housing Authority, a representative pointed to an April 2012 press release of PHC’s appearance at a press conference announcing the plan to fill 2,000 jobs.

Another signatory on the CBA was the New York City chapter of the National Association of Minority Contractors. The agreement committed the developer to dedicate 20 percent of construction dollars to minority-owned firms and 10 percent to women-owned firms. A report from May found that out of the $558 million spent on contractors, the goals came close: 16 percent were for minority firms and 6 percent went to woman-owned firms. The contractors referred questions to Delia Hunley-Adossa, head of the Brooklyn Endeavor Experience and CBA coalition chair.

Before signing the CBA and launching BEE in 2005, Hunley-Adossa was a housing representative in the Atlantic Terminal complex and head of the Precinct Community Council that represents Fort Greene. Among the $400,000 her group got from Forest City Ratner, she told the Daily News in 2009, much of went to air conditioners, rat abatement, environmental awareness classes and trips to summer camp.

That year, she also lost a race to unseat City Councilwoman Letitia James, whose district includes Atlantic Yards. James remains a prominent Atlantic Yards opponent. During the debate for that campaign, Hunley-Adossa admitted the group’s work was at a “standstill” and would proceed once ground was broken. Its website hasn’t been updated since 2010. Hunley-Adossa didn’t respond to e-mail and phone requests.

Another signatory is Joseph Coello, chairman of Brooklyn Voices for Children, formerly the Downtown Brooklyn Education Consortium. BVC was charged with helping plan for schools within the site footprint, handling at-risk youth employment and housing seniors. Coello said that though BVC had been largely dormant, he would begin to reinvigorate the group in 2013.

“The project stalled for a while,” he said. “For a few years, there was no real reason for us to start to worry about how do we put a charter school here. You had to get to the stadium, you had to get to the housing before our part starts to kick up.”

Forest City officials say there’s no plan to sign a new CBA, and though some players have changed, Coello said there’s no reason to. But he was open to adding more groups and said that it’s possible for some of the existing groups to take over BUILD’s mission. “We’ll be looking to either replace BUILD or to somehow modify some of the other groups. You know, maybe every group taking on partial pieces [of its implementation plan],” he said.

According to Coello, one of those plans is to again reconstitute, expanding the little-known BVC consortium from four organizations to six or seven.

“We’ve got a full 30 years to go” as stated in the CBA, Coello said. “It may not be in my time [as BVC chair]. But it’ll be somebody’s.”

Around the same time Bruce Ratner left the bureaucracy of New York City government in the 1980s to become a real estate developer, the well-known progressive advocacy group ACORN set up shop in the city and quickly gained a reputation for its affordable housing work. With its ability to turn out members at rallies, protests and public hearings of all kinds, the group became an important ally in City Hall.

Though both Ratner’s real estate company and the liberal organizing group were aligned with the Democratic Party, the two often found themselves at odds. In 2000, ACORN even protested in the lobby of Forest City’s Brooklyn offices, calling for a living wage at the Atlantic Terminal Mall. (“It was love at first bite,” cracked Ratner during the B2 groundbreaking.)

So it was somewhat surprising to many when, four years later, ACORN CEO Bertha Lewis came out as a supporter of Atlantic Yards. The influential activist signed a memorandum of understanding, pledging support for the project in exchange for promises that it would include affordable housing.

The affordability requirements tie into structural criticisms that housing organizations have long opposed. Like at other developments in New York, the Atlantic Yards affordability requirements depend on the Area Median Income calculation that includes wealthier parts of New York and its suburbs. Though the American Community Survey estimated the median income for a family of four in Brooklyn was less than $45,000 in 2011, the AMI uses a median of $83,000 to factor its affordability. At least 20 percent of the subsidized units in B2 are reserved for families making more than $100,000. In short, spaces reserved for “working-class families” will go to wealthier New Yorkers.

“A family making $111,000 a year is going to need subsidies in order to afford the rents they expect to charge at Atlantic Yards,” said Vogel.

“People try to say, oh, you’re only saying that for your 30 pieces of silver. Are you kidding me? I mean, we existed before Atlantic Yards, we will exist after Atlantic Yards.”

The arrangement has attracted plenty of critics. “The pattern of this project is going to be to re-divert affordable housing subsidies to help finance a luxury project, not for the intended purpose, which is to house working people,” said Gib Veconi, treasurer of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council and an early skeptic of the development.

Lewis, who now heads The Black Institute, described how ACORN developed a half-affordable, half-market rate model in the early 2000s, but was rebuffed by developers before Forest City proposed Atlantic Yards.

“I mean, we sat down with a developer who said to us, ‘if I make one penny less than I can, than I consider that a loss’,” she said. With ACORN dissolved following a national scandal, the Mutual Housing Association of New York is managing the affordable housing for Atlantic Yards, though Lewis is still a figurehead for the housing effort. She characterized the fight as ongoing.

“People try to say, oh, you’re only saying that for your 30 pieces of silver,” she said. “Are you kidding me? I mean, we existed before Atlantic Yards, we will exist after Atlantic Yards.” Lewis added that the group was used to getting funds from various sources, like it did from Forest City, which gave them money and a low-interest loan. “People say ‘well Forest City contributed and gave you a donation.’ So did Robin Hood Foundation, so did New York Foundation, so did this or that. You know, we are a group that seeks funding for all of our programs and they’re just another one of them. So the reward to us when people say ‘you sold out’: We’ve sold out for 2,250 affordable units that we have to work our ass off everyday to make sure that happens.”

“But here’s what we know,” she went on. “We know in the end, we win. Because in the end, we would have fought to make this project come about the way we said. And our revenge will be that the critics will see what we said we were going to do get done, and there actually can be a partnership between the community and a private developer.”

Speaking at the groundbreaking, she confessed to being a little nervous. “I feel like I’ve been pregnant for eight years, and finally we’re going to birth this baby,” she said to laughs, especially from members of New York Communities for Change, the reformed ACORN group, seated in the rows behind the press. “And I’ve got 14 more to go, so thanks for knocking me up, Bruce.”

That baby, a hybrid of megadeveloper ambition, community-oriented gestures and recession-tinged cost cutting, will make its mark in Brooklyn. The affordable units will help New York’s housing shortage, but as mammoth at Atlantic Yards is, the first 181 units in 2014 will be small drop in a running total of what the Bloomberg administration anticipates to be 165,000 affordable units created or preserved since late 2002. According to Forest City officials, the groundbreaking for the project’s third building is tentatively planned for sometime in early 2015, a full 20 years before the last modular building is scheduled to rise.

Starchitect Frank Gehry created the first design for Barclays Center but when the project was ready to move from planning into construction phases, developer Forest City Ratner switched to a more affordable design by SHoP.

But while Atlantic Yards arrives, Brooklyn goes on.

There is already tangible change from Atlantic Yards. Home team pride has kicked up business at the Modell’s across from the Barclays entrance, as Nets fans don the team’s black and white gear. Boutiques and high-end restaurants are slowly appearing along Flatbush Avenue. A couple of blocks away, Triangle Sports, a family sporting goods store that opened in 1916, closed early last year. Last September, the three-story building sold for $4.1 million in what the Brooklyn Paper called “a new record among comparable retail buildings in the borough.”

Nobody really knows what the borough will look like when the project’s 6,430 housing units are finished sometime around 2035. As a point of comparison, since a 2005 rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn at least a dozen luxury high-rises and condo-conversions quietly sprouted more than 3,500 units of mostly luxury and some below-market rate housing. Many more are planned.

If development continues apace, much more of Brooklyn’s Central Business District will resemble Atlantic Yards’ crisp vertical renderings before its own site does (especially if the Navy Yard’s modular construction project — pioneered for Atlantic Yards — catches on). Right now, the developers are working on a court-ordered environmental impact study of what a 25-year construction site means for neighbors. But nothing in crowded New York is a vacuum, so no study can predict what really happens in Brooklyn. Can growing municipal budget shortfalls pop a Brooklyn real estate bubble, pulling the rug from under Atlantic Yards financing? Post-Hurricane Sandy, will tenants flee flood-prone Lower Manhattan for the relative high ground of Downtown Brooklyn? Or what if the Brooklyn Nets are just really bad?

Just a few weeks before its collapse, BUILD’s office was a hive of activity, filled with some of the estimated 150 walk-in applicants per month. In an interview in October, Caldwell said the group had helped place 175 people at the Barclays Center, as well as 600 at other locations, including BUILD’s own office, since 2007. One man, he recalled, had been in jail for nine years and was, upon release, unable to find work. “We got him a job at the Barclays Center,” Caldwell said. “With a picture with the owner, Mr. Bruce Ratner himself.”

But aside from the issues with its apprentices, problems at BUILD seemed to come from within. Last September, a complaint from a recently fired executive to the state attorney general emerged on the Atlantic Yards Report. Former CFO Lance Woodward alleged that BUILD was in peril — it owed $115,000 in taxes — and that Caldwell himself had misallocated thousands of dollars on unapproved expenses like food, transportation costs and Nets season tickets. Caldwell said they might buy subway fare, food or clothes for job interviewees. In other cases, he said, they brought neighborhood children to a Pennsylvania amusement park or to see the Nets play in the team’s old home of New Jersey. Caldwell was proud of his efforts, even if he had to admit he’d gone a little rogue.

“I tend to get the business in trouble — a non-profit organization in trouble — by making decisions like that,” Caldwell said. “But, you know, is it wrong? Yeah, maybe it’s wrong, according to the budget or whatever. But is it right for the people? Yeah.”

Though the group was supposed to extend into the next phase of construction, BUILD shut down abruptly in mid-November. A goodbye letter and a sign on their window listed 22 other workforce development agencies. Reached by phone, BUILD’s employer services coordinator, Daisy James, said the decision to close, which came at the end of October, was a mutual one between Forest City and BUILD. “When we heard that we would be closing,” she said, “it was a little surprising.”

“It wasn’t due to any fiduciary misrepresentation,” James added of the closure, saying they went through a Forest City audit. “We wanted people to know it had nothing to do with finances in terms of Mr. Caldwell misappropriating funds.”

Caldwell and other CBA signatories sat near the front row of the groundbreaking. There, Marty Markowitz addressed Ratner from the podium, discounting neighborhood opposition with his characteristic bluntness. “By the way, Bruce, the world didn’t end. Atlantic Avenue is still there. DeKalb Avenue is still there. Flatbush Avenue is still there.”

“I tend to get the business in trouble — a non-profit organization in trouble — by making decisions like that. But, you know, is it wrong? Yeah, maybe it’s wrong, according to the budget or whatever. But is it right for the people? Yeah.”

In fact, because those streets are ground zero for development, Ratner and other developers don’t need reminding. Perhaps coincidentally, a hole in the ground between Flatbush and DeKalb was the subject of a protest, happening concurrently with the tail end of the groundbreaking. There, community organizers and union construction workers crowded between a billboard-bearing flatbed truck and an Armani Exchange, protesting non-union wages for the coming phase of City Point, an enormous mixed-use project slated as Brooklyn’s next tallest building.

Among the protesters was Nashaun Garrett, a resident of Farragut Houses and member of Families United for Racial and Economic Equality (FUREE), a housing-focused community group. He said the development was business as usual, as groundwork for development is five or 10 years ahead of the community. “So while we’re still fighting and pushing, they’re already laying out the plan to continue to do what they’re doing,” Garrett said. “And they’re not going to stop until… it’s saturated, until everybody who can’t afford to live here is gone.”

For those protesting non-union wages, gentrification and displacement, the venue had changed, and the fight was at its next flashpoint. Among those at the protest was LaBarbera, fresh from the B2 groundbreaking. Signatories of the community benefits agreement, including Caldwell, were at a post-groundbreaking lunch inside the Barclays Center.

The changes in Brooklyn reflect broader demographic and policy changes reshaping the city. To date, the Bloomberg administration has rezoned more than a third of the city’s land area, more than any other in New York history. Large projects are progressing across the five boroughs, from the Bronx to Manhattan’s West Side, where the Hudson Yards megaproject is underway, and Willets Point in Queens, with a controversial plan to replace 62 acres of auto repair shops with housing, a hotel and convention center, also tethered to a major sports complex named after a bank. Consequently, Atlantic Yards is just one wave — albeit a very large one — in a vast tide of redevelopment.

One of the wave’s biggest drivers is Forest City, a Cleveland-based company with scores of properties across the United States, particularly in the Tri-State area. (Its New York subsidiary is Forest City Ratner, named for Bruce.) In the 1990s it developed the MetroTech Center, a 3.7 million-square-foot office and university complex. And just across the street from the Barclays Center is the Atlantic Center and Atlantic Terminal, an enormous enclosed shopping mall, office tower and transportation hub. Those massive projects have already been absorbed into Downtown Brooklyn.

Ten years later, Atlantic Yards is as polarizing and amorphous as the pre-rusted steel that covers the Barclays Center. In fact, it’s easier to assess the process of Atlantic Yards than the project itself, particularly since any sizable benchmarks are years away.

The Nets’ branding is just as much about Brooklyn and its stylish identity as it is about basketball.

Locally, Robert Perris, the district manager for Downtown Brooklyn, said he sees “Atlantic Yards fatigue” and resignation across the neighborhood as people watching the project for nine years see the plans change bit by bit and get used to a gradual whittling down of the project’s objectives. “I think that for many people, a sense of resignation has just sort of taken over where, you know, as each additional fact comes out that is inconsistent with the original plan,” he said. “People just sort of say, ‘but of course, hasn’t that been the way this project has gone all along?‘”

Perris pointed out that people can’t get nostalgic for the charming Brooklyn of Vinegar Hill if all they know are the Farragut Houses and others like it that rose amid the neighborhood. Similarly, he said, “there will come a time when there’ll be some degree of Atlantic Yards that has been constructed, and people who move to Brooklyn after that will just sort of accept that as a given. It is the landscape that they know. They didn’t know a different Prospect Heights or a different Vanderbilt Yard.”

The beginning of the key housing benefit of Atlantic Yards is a good time to look at whether the CBA’s goals of catalytic changes and long-term benefits have happened. With B2, there’s potential for announcements over the next few months from some dormant groups, some cash infusions and possibly a long-promised compliance monitor. But at this point, the CBA has changed little in Brooklyn. To many, the promised jobs have been underwhelming and the responsibility for maintaining them remains in limbo. Blunders or marked lack of progress hit some of the groups responsible for maintaining benefits. And given the quixotic nature of the way benefits went out, there’s not yet a structure for more lasting benefits, at least until the schools, homes and transparent non-profits exist off paper.

For many urban residents, redevelopment and gentrification are two sides of the same coin. Because of that, CBAs are coming into play to help allay equity concerns, particularly where public subsidies are involved. Some critics call for political reform to make subsidies more transparent and accountable. To Angotti, it depends on the vibrancy of community movements and changes in government. And he’s not that optimistic about changes in government — like giving community boards, which opposed the project, more power.

“Many people just don’t have any confidence that their views will make any difference anyway,” he said. “So, the very common reaction of people is ‘well, what we say doesn’t make any difference anyway, so the best that we can ever hope for — even under the best of conditions — is to get a piece of the action.’”

For now, it seems that the biggest incentive keeping benefits rolling in New York hasn’t been the agreement, but to maintain legitimacy to move to the next project. As Angotti noted, “I presume that to sustain any credibility for future development, Ratner’s gotta produce something.”

In the larger picture, Joseph McDermott, executive director of the Consortium for Workers Education, a workforce development non-profit that funded BUILD and other agencies, said many CBA job guarantees could be misleading.

“People will guarantee X, Y and Z construction jobs,” he said. “Well, if those are unionized construction jobs, nobody has a say, in a sense, as to who’s gonna work on that site. It’s governed by contract, it’s governed by seniority and it takes someone a good long time to get through — if they can get through — the apprenticeship process.”

But still, developers offer up job promises. “It’s easier to say ‘I’ll employ 40 people. Here, I’ll give you a hardhat and a flag, you can wave some traffic by.’”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Dan Rosenblum is a New York-area writer. He graduated from the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism and has contributed to City Limits, Capital New York, Jersey Journal and other publications. Only half of those who follow him on Twitter are Spam bots.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine