Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThere was something both amusing and disheartening to George Wolfe about the fact that the Los Angeles River was not, according to the federal government, technically a river. As the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers saw it, the L.A. River was “non-navigable,” meaning the waterway would never float a boat or host swimmers. This meant that it didn’t have to be kept clean like a “real” river, and would be held to a lower standard of environmental protection.

That was the disheartening part. The amusing part was that Wolfe knew very well that one could, in fact, navigate the non-river — he had done it himself. So Wolfe, a former editor of a satirical news website and a keen observer of political absurdity, decided to prove the Corps wrong.

In July 2008, Wolfe and about a dozen others plopped kayaks and canoes into the L.A. River near its concrete headwaters and set off on what would be a three-day, 51-mile boating and camping trip down a waterway that most Americans know only from Hollywood action scenes. (The river has taken star turns in hundreds of TV commercials and small productions, as well as in Grease and Terminator 2: Judgment Day.) Wolfe and what he calls his “small armada” made headlines. For river advocates, the trip went down in history as the game-changing push the Environmental Protection Agency needed to overturn the Corps and declare, two years later, that the river was navigable after all.

This change in mentality — and legal status — set the stage for what could be the next big transformation for Los Angeles, and even Southern California. Running its first 32 miles within L.A. city limits, the river cuts through another 13 cities on its way to a utilitarian ocean spillout next to the huge Port of Los Angeles. But more than anywhere else in the region, the river’s identity is enmeshed with the city center. More of a polluted flood control channel than river, the waterway has long stood as a symbol of L.A.’s degraded culture and alienation from the environment. Now on the verge of revitalization, the same river represents renewal and connectivity.

Wolfe’s river has gone from being a fringe concern to an established priority breathlessly championed by everyone from grassroots activists to Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. “Revitalization” is its new accompanying buzzword. Flashy renderings imagine a renewed river with less concrete and more life and activity. Community visions foresee a network of parks on its shores. And, thanks to a growing ecosystem of organizations concerned with its future, plans are now in place to bring about that transformation.

To planners and advocates, the river’s reinvention means an opportunity to redeem L.A. from its history: One of top-down development that prioritized growth at the expense of the environment and those communities not in positions of power. Unlike the projects that have defined L.A. until now — its web-like complex of freeways, its archetypal suburban sprawl — the river’s reinvention came about not only because there was money to be made, but because a large and broad constituency of city residents wanted it to happen.

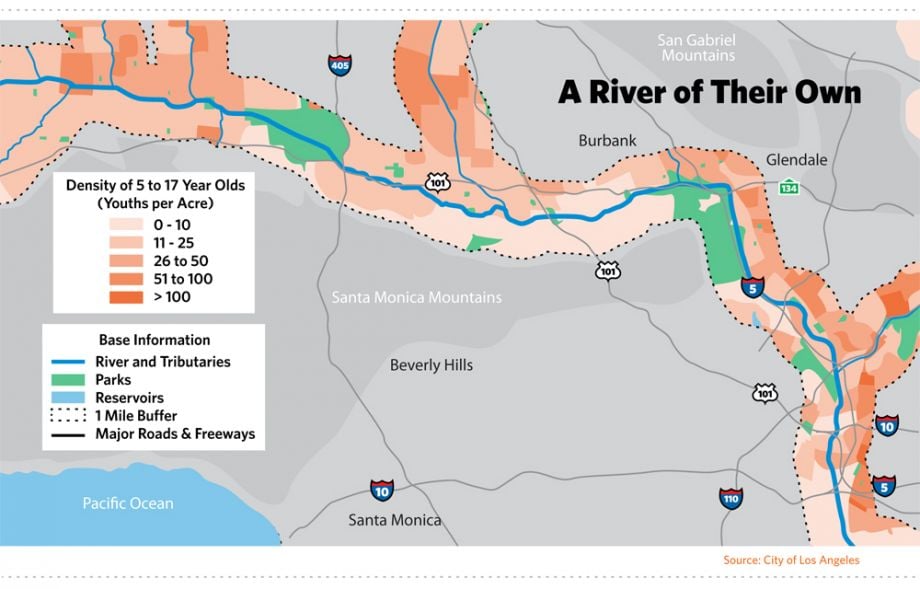

Mia Lehrer, landscape architect for the Los Angeles River Revitalization Master Plan approved by the city council in 2007, describes the river in its current state as a “gash” dividing less affluent, majority-minority East L.A. from wealthier and whiter West L.A. Healing it will mean bridging the two sides of the city and, hopefully, bringing divergent communities together in ways that benefit everyone.

“It’s a big canvas for developers to reconceptualize or reimagine infrastructure in a way that really balances people, jobs, public space, development, public-private benefits,” Lehrer said, “so that it’s not just about solving one problem.”

The river’s rebirth is one of a thousand tiny moments, with small parks opening along its banks, accessibility increasing and the ambitious makeover outlined in Lehrer’s master plan gradually rolling out. At the foundations of this rebirth is a dedicated and growing group of river advocates, people like George Wolfe, who saw potential when most saw a concrete ditch. These advocates, small in numbers early on, rallied to create a vocal and visible constituency of stakeholders concerned with the river. Beginning in the 1980s, they began to make a case, proposing ideas about what the river could be: Instead of bemoaning or ignoring it, as was the city’s usual course of action, it could become the connector Los Angeles needs. It could provide park space in a crowded metropolis of 3.8 million and the county of nearly 10 million that surrounds it. It could engender a sense of natural pride for a place long associated with the materialism and gridlock of modern America.

Over time, these voices have grown louder and their ideas have turned from pipedream to practical. A once-narrow constituency of river advocates has swelled into an ecosystem of forces implementing revitalization on a scale Robert Moses would admire. And it’s being done in a way that Moses, with his brute political force and disregard for community input, would find utterly foreign.

Today, after years of gradual effort, the Los Angeles River is finally becoming a part of the city. In an era when government is increasingly looking to private individuals and organizations to conceptualize and even finance parks and other public spaces, the story of this movement to resuscitate the L.A. River is instructive to communities wondering how to reactivate their own fenced-off treasures.

Before it had a name, the Los Angeles River was the reason Spanish explorers in the late 1700s decided to build a mission that would eventually grow into the second most populous city in the United States. For more than 100 years, the modest river provided all the drinking and irrigation water the small settlement needed. Flowing mostly underground, it turned the area in and around Los Angeles into the country’s most productive agricultural land up into the 1950s. This fertile ground lured tens of thousands to Southern California in the late 1800s, carried along by the recent completion of the transcontinental railroad. The river would soon become a victim of its own success, as its agricultural prowess had lit the fuse of a population explosion.

The city’s first official census as part of the U.S., in 1850, counted just 1,610 people. By 1890, there were more than 50,000, and just a decade later the population had topped 100,000. The rate of growth stressed and altered the river. Riverside farms were rapidly sold off and subdivided into housing for the onrush of new residents. A relatively meager surface flow and the semi-arid region’s periodic droughts made it impossible for the river to keep up, leading to a still-ongoing era of finding and importing water from outside sources. Its insufficient supply could and would be engineered around, and as new sources of water became available from the Owens River Valley and the Colorado River, the Los Angeles River drifted into the background of the city it had brought to life.

But every once in a while, the L.A. River forcefully reminds the region of its presence. The many tiny streams and arroyos that trickle into it are fed by rainwater from the nearby San Gabriel Mountains. And though much of the rainwater soaks into the porous geology of the region, there are occasions when the downpour is so strong and persistent that the typically small river instantly turns into the sort of raging rush of water the word “river” illustrates in the mind. Los Angeles flooded 11 times between 1850 and 1900, inundating farms and washing away homes and irrigation channels. As author Blake Gumprecht explains in his thorough history, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth, the city tried various methods to prevent or reduce flooding in the 19th century, but small dams were repeatedly washed away and efforts to limit development in the floodplain were largely ignored.

As the city continued to attract residents throughout the early 20th century, this unhindered growth would prove increasingly destructive. A major flood in 1914 inundated nearly 19 square miles in Los Angeles County, washing out numerous railroad bridges and levees and turning swaths of the region into temporary lakes. A smaller but still-destructive flood occurred in 1916. Frustrated politicians pushed a series of successful bond issues in the subsequent years to fund flood control efforts like dams and reinforced levees, but voters eventually grew weary of the costs. Despite the fact that a steadily growing amount of people were living in flood-prone areas, the public was no longer willing to pay to prevent floods they weren’t completely sure would happen again.

On New Year’s Day in 1934, the water returned, this time demolishing nearly 200 homes in newly annexed land near the mountains, killing 49 people. Unable to pay for the sort of controls needed to prevent further devastation, the county turned to the federal government. Using New Deal funds, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a massive flood control plan for the watershed of the Los Angeles River. Less than two years after the New Year’s Day flood, concrete walls were being poured along the sides of some sections of the river. In 1936, Congress approved the Flood Control Act, which gave even more power to the Army Corps to prevent flood damage. And that came in handy after another even more destructive flood in 1938, which killed 87 people and inundated 168 square miles across the county. The Army Corps decided almost immediately that concrete river walls weren’t going to be enough. Within months, the concrete began flowing, filling in the sides and pretty much the entire bottom of the riverbed in a 51-mile channel to the ocean.

Altogether, about 3.5 million barrels of concrete — nearly 200 million gallons — were poured over the next two decades along the river and its tributaries, about as much as a week’s worth of the river’s discharge into the Pacific Ocean. Once channelized, the river flowed to the ocean year-round, though typically in small enough volumes that a long jump could take you from one bank to the other. Given the river’s wildly variable flow, it’s difficult to say how much water it would have carried on average, but one city estimate suggests that the average flow was probably something like 200 cubic feet per second after the concrete was laid. The Mississippi River, by unfair comparison, has an average discharge in New Orleans of more than 600,000 cubic feet per second.

That changed in the 1980s with the opening of the Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant. Located on the river’s bank, the wastewater treatment facility processes the residential and commercial sewage of the city’s suburban San Fernando Valley, discharging at least 20 million gallons of treated wastewater into the body of water every day. This slightly more significant flow had a noticeable impact on the river’s modest ecosystem of plants and animals, but these subtle changes weren’t enough to distract human beings from the river’s channelized reality. Indeed, by the late 20th century, the river that had drawn Spanish settlers 200 years earlier had become an easily overlooked piece of infrastructure that sometimes played a river on TV.

From the side of a four-lane overpass in the Canoga Park area of the San Fernando Valley, 25 miles northwest of Downtown L.A., you can look down on the official headwaters of the Los Angeles River. Two concrete canyons converge, their 20-foot walls perfectly vertical and smooth, curving to meet like two lanes merging on the highway. Here the water runs just a few inches deep and spreads across a maybe 100-foot channel. On the other side of the overpass, the water below narrows into a single body and the concrete walls fan out into a trapezoid shape, shooting the river straight off into the distance.

The clean lines and angles, the plain concrete grey, the modernist infrastructure — it’s all kind of beautiful, both crude and elegant. It’s a brutish way to treat a river, but one so efficient that it’s impossible to discount the precision and scope of its engineering.

And so it goes, 51 miles to the Pacific Ocean, alternating its vertical and trapezoidal walls as it carves through the urbanity of Greater L.A. Walls climb more than 30 feet in some parts, topped off by fences and signs warning passersby that entering the river is a crime. For those not scared by the warnings, some parts of the river are relatively easy to access, with a little fence jumping and train track hopping. Once on the concrete surface of the river’s channel, there’s a distinct feeling of increased calm, even near downtown or the bustling train yards and warehouses along its sides. You’re not exactly separate from the city, but just a degree or two away from the usual background buzz. It’s the ideal environment for graffiti artists and the homeless, or even the lone egret flying low and smooth over the river between its protecting grey walls.

Though most of the channel is covered in concrete, there are three separate stretches, totaling about 12 miles in length, where the earthen riverbed is still intact. The underground water table is too high in these areas to cooperate with the Army Corps’ concrete plans, so they were left at least partially natural. Willow trees grow, ducks swim, cattails sway in the breeze. For a few miles in a few areas, the Los Angeles River has always been a river.

By the late 20th century, the river that had drawn Spanish settlers 200 years earlier had become an easily overlooked piece of infrastructure that sometimes played a river on TV.

That’s how Ed Reyes remembers it. The longtime L.A. city councilmember grew up just a few blocks from a natural-bottomed stretch of the river known as the Glendale Narrows. He remembers crossing over railroad tracks as an 8-year-old kid back in the late ’60s to get to the water.

“We skidded our Schwinn bikes down to the base of the river and found this running water,” Reyes recalled in a recent interview. “There were all kinds of bushes and trees and ducks in there, and in the middle there was like a little beachhead with sand.” Reyes and his brothers used to catch tadpoles and listen for frogs, he recalled. They’d even swim in the water — and bring its stench back home with them. “We didn’t know what was in there at the time, of course.”

Whatever chemicals and pollutants the water carried, the river was a welcome change to the gang-dominated parks and dangerous streets of that part of town. “As a kid, that was my sanctuary,” Reyes said.

Since taking office in 2001, Reyes has been one of the river’s strongest political advocates, forming the Los Angeles River Ad Hoc Committee and spearheading efforts for revitalization. Like so many others growing up or living near the river, Reyes understands it to be much more than a concrete drainage channel.

But the river of Reyes’ childhood and the river of today are vastly different for one major reason: water. The increased water flow created by the development of the Tillman wastewater treatment facility allowed more plants and wildlife to thrive in the river’s three natural-bottomed areas. All of a sudden, the technically ambiguous river was looking more like a real one.

“The opening of that plant was one of the most significant events in the history of the river,” said Lewis MacAdams, a longtime advocate for revitalization. Shortly afterward, MacAdams started what would become, arguably, an even more important era in the river’s history by creating the advocacy group known as the Friends of the Los Angeles River. A poet, teacher, performance artist and L.A. transplant, MacAdams discovered the river in the early ’80s not long after moving to town and instantly became interested. After a few years of ferment, that interest grew into action when, in the form of an art performance, MacAdams attempted to personify the river and its animal inhabitants in an effort to call attention to its dilapidated state. Almost 30 years later, MacAdams remains the river’s principal evangelist and has been one of the most active participants in efforts for its reimagining.

“I think I was just on a voyage of discovery,” MacAdams said of the early days of his involvement. “There wasn’t anything behind it or any kind of theory, other than maybe just a kind of yin-yang idea that the river was so fucked up that it could only go one way: It could only become less fucked up.”

MacAdams wasn’t the first person to see potential for the river to be reborn. In 1930, eight years before the river was channelized, the eminent landscape and planning firms Olmsted Brothers and Bartholomew and Associates envisioned the river as the connective tissue of a series of parkways that would make up a broader network of green spaces throughout the city. That plan, “Parks, Playgrounds and Beaches for the Los Angeles Region” painted a picture of the Los Angeles basin as a wonderland of parks that appears almost cartoonish as a counterpoint to today’s lack of open space. Despite its comprehensive nature and details on how to fund and implement the vision, the plan was trashed shortly after completion. Though elements of its river-focused parks vision are reemerging today, the plan is seen widely as a missed opportunity and Los Angeles remains one of the most park-poor big cities in the United States.

But the city understands that has to change, and the idea of spending public money on parks is politically viable in 21st-century L.A. In the fall of 2011, Villaraigosa announced a plan to build more than 50 small pocket parks throughout the city over just two years. Only a handful has opened so far, but officials are actively securing sites and beginning construction on more. And in July the city opened a new 12-acre park downtown, hoping to help transition the area into a new cultural hub for the city.

The series of small park spaces opening along the river underscores this trend. The L.A. of the 1930s may have wanted park space as badly as the L.A. of the 2010s, but the political climate today is making even very ambitious projects like the River Revitalization Master Plan appealing to leaders and business people who, 80 years ago, might have turned their noses to such a prospect.

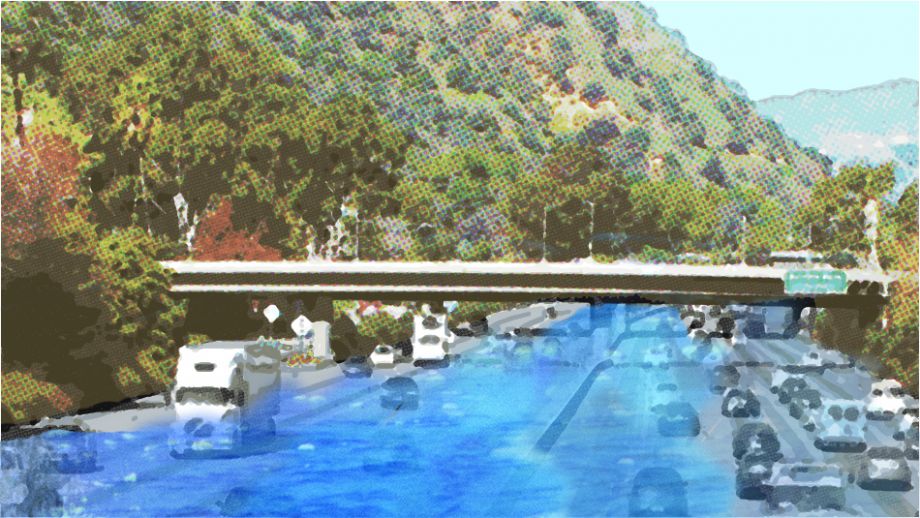

California Assemblyman Richard Katz was serious when, in 1989, he suggested the river be turned into a freeway. The idea had come up a handful of times over the years — before their 1930 plan, Olmsted and Bartholomew had suggested turning the concrete-free waterway into a “river truck speedway.” But this time, the proposition seemed to stick; it offered a possible way out of the congestion and gridlock with which the city had by then become synonymous. Katz, who served as chair of the Assembly’s Transportation Committee, said that allowing buses, carpools and trucks to drive on the river during dry months would lessen congestion on nearby freeways between 15 and 25 percent. That got officials listening. A $100,000 report was commissioned.

For MacAdams and the burgeoning Friends of the Los Angeles River, Katz’s idea became a perfect rallying cause. Because of all the attention it gathered, more people were thinking about the river and what — or what not — to do with it. The river-to-freeway idea eventually floundered, and from then on the river’s constituency began to expand. Much of that constituency was at the grassroots level, with hopes for change that did not involve driving trucks on the riverbed.

It was part of a shift that’s still unfolding today. More and more people have become interested in a Los Angeles that embraces its natural elements rather than paving them over. River revitalization efforts and park creation are manifestations of a growing culture that repudiates the city’s car-centric reputation. In the late ’80s, though, this wasn’t exactly the zeitgeist.

“The river doesn’t run through any wealthy neighborhoods,” MacAdams said. “We’ve never been part of any particular power structure. We’ve never had an actor or actress represent us. People used to always say ‘who’s your celebrity?’ and I’d say ‘the river.’”

For a number of people, that was enough. Joe Linton, an early member of the Friends of the Los Angeles River, said it was easy to get people hooked.

“We were leading walks in the 1990s where we would cut the fences and walk people along areas that weren’t officially opened to the public. And as people used those areas for walking, they kind of assumed that they were public,” Linton said. “Then they become public, even if they’re not explicitly legally public.”

With interest growing, then-mayor Tom Bradley realized in the early ’90s that he couldn’t just ignore the river. He appointed a task force in 1990 that would eventually suggest ideas for making the river more of an asset to the city, such as adding bikeways along one section and cleaning up another of the natural-bottomed areas. Built a few years later, these bikeways were the first major projects that began to turn the river from an off-limits storm drain into an accessible recreational amenity.

Throughout the ’90s and early 2000s, the river’s stakeholders grew in number. A wide variety of interest groups formed to, at least partially, advocate for a cleaner and more connected urban river. Along with Friends of the Los Angeles River, groups like Tree People, Heal the Bay, North East Trees, the River Project and the Los Angeles Conservation Corps became more active and vocal. Guides were offering unofficial tours of the river, and boaters were taking advantage of its flow. The grassroots were growing.

By the time the city began to write a master plan for the river’s future, a significant coalition of activists was working with leaders at all levels of government. The master plan, approved in 2007, contains a broad strategy for transitioning the river’s 32 miles running through L.A. into places for recreation, natural life, water quality improvements and, crucially, flood control. Slick renderings show a tree-lined river with grasses and bushes growing up from the water, and terraced sides that allow and encourage people to come down to the banks or even swim. Parks, bike paths and pedestrian walkways would adorn the river at every turn. Surrounding neighborhoods would benefit from access as well as improved infrastructure, new development opportunities and the economic changes that come with recognizing the potential of a natural asset.

There are nearly 20 projects now being built to increase public access to the river, from greenways to park expansions to two new bridges. One of those bridges, in the North Atwater neighborhood, will be a philanthropist-funded pedestrian/cyclist/equestrian crossing that will begin construction this spring — the first such project on the river. The other is a more significant $401 million replacement bridge connecting downtown and East L.A. that includes an ambitious amount of park space and river access below — a project many see as a potential new icon for the city.

River revitalization efforts and park creation are manifestations of a growing culture that repudiates the city’s car-centric reputation.

The cost of rolling out the Revitalization Master Plan as designed would fall somewhere in the area of $3 billion. Funding will come from a wide variety of sources, including city, state and federal money, as well as newly available funds from the White House’s America’s Great Outdoors initiative. The federal government is expected to cover 65 percent of the costs, with the city raising the rest however it can. To help with the project’s complex funding, the master plan established the non-profit L.A. River Revitalization Corporation, whose job is to wrangle in funding sources from government, philanthropy and the private sector to help implement the plan’s many parts.

“I call it lasagna financing,” said Omar Brownson, the corporation’s executive director. “We need to layer public, non-profit and private capital and still make it taste good.”

It’s a mechanism for getting things done that has worked for other cities with ambitious projects. New York City’s High Line, for example, cobbled together city and federal money and combined it with a significant amount of private money raised through the non-profit Friends of the High Line, the group that came up with the idea for the park and which is also responsible for its day-to-day operations and costs. The High Line was implemented through a formal city plan, but it really came to life because of grassroots momentum. This same process is unfolding in Los Angeles.

Given the scope of the L.A. plan, it’s been slow going to generate the funding necessary to make major changes. Still, the small steps continue. In the near term, the city and river advocates are awaiting the delayed completion of an Army Corps study on the feasibility of restoring the ecosystem along a 10-mile stretch of the river, which includes large areas never covered in concrete. If that study turns out as expected, it will ease the process of implementing projects set out in the master plan.

“We’re right at the pivotal point,” Reyes said.

It’s both right and wrong to think of this as the moment of the Los Angeles River’s rebirth. It’s right because of so many recent accomplishments and improvements, physical and logistical. But it’s wrong because the scope of the river and the political intricacies of bringing about those changes are so complex that there can be no single point of comprehensive success.

“It’s going to take at least as long to undo the past mistakes as it did to implement them,” said Linton, the longtime river advocate.

Dr. Carol Armstrong, who runs the city’s river office, said that, given the long timeline, the most appropriate way to measure success in the river’s revitalization is to watch how it becomes a larger part of the daily lives of people in Los Angeles. “Not just to say ‘we attracted the Olympics,’ but ‘I walk my dog there’ or ‘I do my yoga there’ or ‘my marathon class trains there’ or ‘that’s where I read my book,’” said Armstrong. “It’s not just a backdrop to a movie, a car commercial or a murder show.”

“Whether it’s pretty or ugly, the river’s going to be there. You’re just hurting or making yourself feel bad if you think it should go faster.”

That process of reconnecting the river with the people is gradual and ongoing, materializing in the sort of piecemeal improvements that have sprouted recently — pocket parks, half-mile walkways, neighborhood-driven beautification efforts. This is what progress looks like, but some say the river needs bolder action.

“Those were baby steps of the last 10 years,” said Lehrer, the landscape architect. “They were great, they were so important. But we cannot continue thinking on baby projects. We need to think big.”

But without strong leadership from the top, that won’t happen. Lehrer said that jurisdictional squabbling between the city and the county has sometimes gotten in the way of the large-scale implementation a river project requires. But Reyes argues that the political climate is beginning to shift.

“The different jurisdictions are establishing a new culture in how to work together,” he said. “For decades they never had to engage each other at the level and detail that they are today.”

And that’s an improved relationship that will continue to serve the river. But in terms of handing out credit for bringing the river back to the spotlight, it’s the groups like the Friends of the Los Angeles River that have had the most impact. For all they’ve accomplished, though, the river is still a long way from becoming the amenity it could be. The slow pace would seem to be frustrating to the point of surrender — especially for MacAdams, who has been rallying since 1986. But is revitalization taking too long?

“No, I think it has to go at its own speed,” MacAdams said. “Whether it’s pretty or ugly, the river’s going to be there. You’re just hurting or making yourself feel bad if you think it should go faster.”

It’s maybe surprising to hear this from the river’s chief agitator and cheerleader, but nearly 30 years working with and within the system undoubtedly engenders a little pragmatism. And that’s why MacAdams, on a typically sunny November day, is standing in front of a red ribbon, behind a podium and next to Villaraigosa. They’re preparing to officially open a new two-mile river bikeway in the valley suburb of Reseda, yet another small part of the river’s makeover. This is the sort of event MacAdams and Villaraigosa often attend, the river advocate serving as a poster child for its resurgence, the mayor happily enjoying the political benefits of ushering in small but needed urban improvements.

Villaraigosa, another L.A. politician who grew up near the river, has made revitalization one of his priorities (though certainly not a main priority) during his two terms. Through a combination of dedication and good timing, he’s been the city’s top official ushering in the spate of milestones that have been met in recent years, and he clearly knows that river efforts started before him and will continue long after he leaves office in June. It’s more than lip service when he tells the small crowd at this opening ceremony that MacAdams is a visionary.

“The dreamers in a city of dreamers, we need them,” Villaraigosa said, the river flowing a short distance behind him. “The people that can close their eyes and see something that doesn’t exist, we need them.” MacAdams spoke for the river when no one else cared, the mayor explained. Now there are ribbon cuttings, boat rides, major pieces of legislation and a whole slate of improvement projects underway. Now, he said, people care.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Nate Berg is a writer and journalist covering cities, architecture and urban planning. Nate’s work has been published in a wide variety of publications, including the New York Times, NPR, Wired, Metropolis, Fast Company, Dwell, Architect, the Christian Science Monitor, LA Weekly and many others. He is a former staff writer at The Atlantic Cities and was previously an assistant editor at Planetizen.

Lauren Adolfsen is a designer and illustrator based in Los Angeles. In May 2011 Lauren received her MFA in Graphic Design from Yale School of Art. Since 2003, Lauren has made claymation shorts and sold retail products under the name Snack Mountain. You can read about her latest projects at blog.snackmoutain.com.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine