In January of 2020, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) began implementing the largest prison drug treatment program in the country. The effort was done to curb an alarming rise in overdoses in California prisons: In 2019, 64 people incarcerated by CDCR died from overdose, making it the second leading cause of death.

This May, however, the Union of American Physicians and Dentists, the largest union representing licensed doctors in the United States, with headquarters in Sacramento, called into question the continued rollout of the drug treatment program, which makes available the three most effective opioid medications to people incarcerated. 138 doctors, who represent a third of the doctors who work in California state prisons, drafted a petition explaining that while they support medication-assisted treatment, they were concerned over the brand-name drug Suboxone and its potential for abuse throughout prison facilities.

Suboxone is controversial as it has “street value” both inside and outside of prison. But it’s a safer drug than methadone, according to the DEA, with less risk of overdose and illegal use.

CDCR’s program provides medical treatment alongside intensive counseling and peer support — care that’s literally unheard of across most U.S. prisons. At San Quentin State Prison, the program is having a marked impact on people who have long struggled with drug addiction and previously had no support or treatment. It has also become a pathway for currently and formerly incarcerated people who successfully overcame their addiction to counsel others trying to do the same.

“This is a harm reduction strategy,” Alex Tata, a counselor with San Quentin’s program, says of the support. “Addiction is a symptom of something greater — until you fix the root of the problem, the addiction is not going away,” she continues. “That’s why I like this work so much, because it gets to the why of the why.”

Drug abuse has become an urgent crisis inside America’s prisons. From 2001 to 2018, the number of people who died of drug or alcohol intoxication in state prisons increased by more than 600%, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In county jails, overdose deaths increased by over 200%.

But treatment is rare, even when people’s crimes are caused by recurrent drug abuse. A 2019 report by the National Academy of Sciences showed only 5% of people with opioid use disorder in jail and prison settings received treatment.

Kevin Flanagan, who has been serving time at San Quentin since 2017, says his experience with heroin turned him to criminal activity. “By the time I was 32, I thought I’d be an addict all my life, I’d come to terms with it.”

He hadn’t received holistic treatment until he became an early enrollee in CDCR’s program in February 2020. He began Medicated Assisted Treatment (MAT) and an in-class program called Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment (ISUDT).

Flanagan says his Suboxone prescription helps keep his desire to use drugs at bay. “That’s with the meds alone, but with the classes, it’s really changed my perspective on things.” The importance of the in-class treatment, he notes, is “learning how to accept myself and my issues, and objectively take a step back and look at my problems in a way I can deal with them.”

CDCR’s program takes about one year to complete. Doctors place participants in the program, then counselors use “motivational interviewing” to encourage them to stay. These are one-on-one conversations where counselors ask clients open-ended questions about their hesitancy of participating. The counselors give clients affirmations and “roll with the resistance,” says Shadeeda Yasin, a counselor with the program.

They often summarize what the client tells them, to “open the door for a dialogue about the client’s program hesitancy,” she adds.

When participants join, they attend two-hour sessions of ISUDT on Monday, Wednesday and Friday in groups of no more than 12. Each session begins with a check-in where current feelings are expressed.

“We need to be aware of what that person is going through at that time,” says Raul Higgins, a certified and incarcerated counselor. “Sometimes a client would shut down, if they’d undergone something traumatic, like a death in the family.”

After the check-in, the group goes through a grounding meditation that takes 3-5 minutes of centering and deep breathing. Then the group begins the curriculum in the workbook Helping Men Recover.

The workbook — grounded in research, theory and clinical practice — is the first gender-responsive and trauma-informed addiction treatment designed for men. “The program explores core issues from social construction of masculinity, the role of anger in men’s lives, impact of abuse and violence on men’s relationships and perceived male privilege,” Higgins says. Part of an effective treatment plan, he adds, “recognizes the physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual aspects of the addiction.”

Tata, who was trained by CDCR to teach two ISUDT classes at San Quentin, says the classes also help participants develop relapse prevention life skills. “It helps them stay on track and meet the goals that they want.”

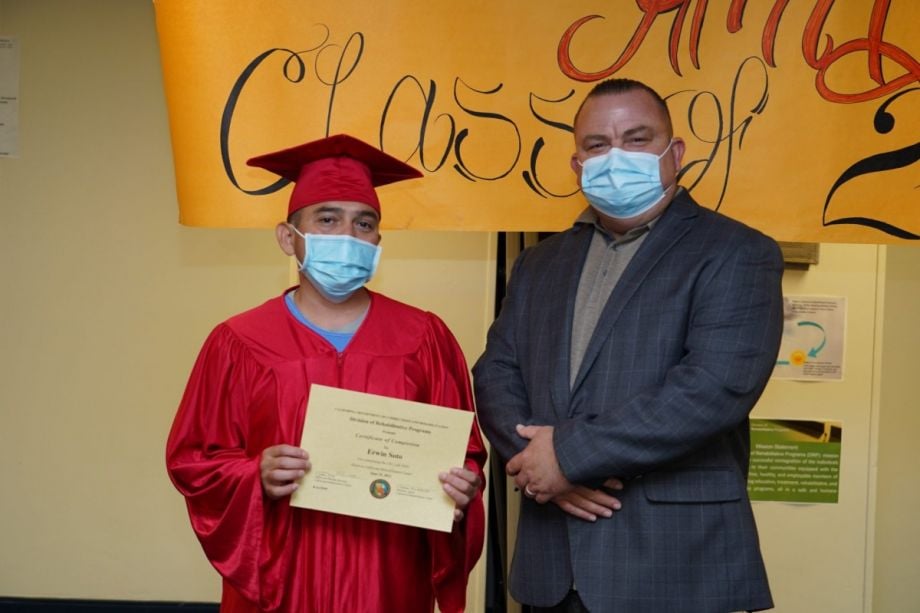

CDCR is currently measuring the impact of the first year of the program. While the department’s official mortality information for 2020 is still pending, preliminary data shows a decrease in overdose deaths, according to Ike Dodson, a communications manager for the program. This June, 13 students became the first graduates under the new treatment program model. As of September 30th, 15,822 patients are receiving treatment for substance use disorder and 12,657 program participants are receiving medication-assisted treatment across all 34 state prisons.

“Staff are working hard to expand access to these services, and [the department] will continue to hire, provide enhanced training, provide technical support and expansion of its provider network,” Dodson says.

At San Quentin, counselors are providing a model of offering personalized treatment despite the prison setting, where mental health care is lacking. Cristina Islas-Banthi, the Associate Program Director for San Quentin’s MAT/ISUDT program, stresses the importance of “a willingness from drug counselors to be open to learn about what’s needed to improve lives,” and clients “to receive guidance and help.” She adds, “I don’t want the participants to feel like they’re a number — we have to get people away from feeling as if they’re a number, they are people.”

Outside counselors don’t do the work alone, however; a core component of the program is the peer support from formerly and currently incarcerated people who have beat their addiction. In 2012, Higgins graduated as a Certified Alcohol and Drug Counselor I, an Internationally Certified Alcohol and Drug Counselor and a Certified Relapse Prevention & Certified Denial Management Specialist for CDCR’s Division of Rehabilitative Programs.

Once he finished the training, he immediately transferred to San Quentin to work side by side with Yasin as a counselor. All counselors, incarcerated and non-incarcerated, meet twice a week to go over the curriculum or issues that may come up in the classes. “For clients to see incarcerated mentors working with someone like me gives the incarcerated population empowerment and builds up self-esteem,” Yasin says. “It’s important to have a good working relationship with incarcerated co-workers.”

“Today, I am a man driven with vision and purpose,” Higgins says. “In my nine years of service, helping and encouraging men with addictions is one of the most difficult tasks of all and MAT is very helpful.”

The currently incarcerated mentors also played an important role during San Quentin’s Covid-19 shutdown. In August 2020, the outside counselors began coming back to San Quentin to deliver correspondence packets of therapeutic lessons taken out of the workbook. Each Monday, the packets were delivered to the incarcerated counselors to give to clients in their respective housing units. The following Monday, completed lessons would be picked up.

About 85 percent of the clients participated in the correspondence programming, according to Higgins. “They wanted something to do,” he said.

This February, ISUDT began in-class sessions in cohorts based on housing units.

“Consistency and stability have been worrying,” Flanagan says about stopping and starting the program during the pandemic. Shortly after the program restarted, the housing unit where Flanagan lives underwent two short quarantines for norovirus. He also learned about the suicide of his cousin. “Having the program available is important to me,” he says.

The continuation of both medical treatment and personalized care will be important to Flanagan’s success upon leaving prison. And the early years of the program have laid the groundwork for real addiction treatment inside U.S. prisons. “My vision is to turn this program into the change where people can come to and have a safe place to be treated like a human being,” says Michael Davila, who was once incarcerated and now is the Program Director for San Quentin’s MAT/ISUDT program.

Davila recalls an interview with a potential client where the client got very emotional: “I asked him why he was so emotional — he told me that it was because he felt like he was being treated as a person,” he says. “To me, I was just acting normally. I saw that he wanted help and I knew this program could provide it. That’s why I want this program to be a beacon for change for anyone who wants it. I want this to be a ray of hope.”

Juan Moreno Haines is a journalist incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison; senior editor at the award-winning San Quentin News; and member of the Society of Professional Journalists, where he was awarded its Silver Heart Award in 2017 for being “a voice for the voiceless.”

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpeg)