Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Donovan is a vendor selling The Curbside Chronicle in Oklahoma City.

Photo courtesy The Curbside Chronicle

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberIn 2011, when Michael Thistle, 60, became homeless after being diagnosed with throat cancer and losing his job, he “spare changed” throughout the five-year ordeal to make ends meet and earn money while he went through treatment.

By saying he “spare changed,” Thistle uses the local vernacular for selling Boston’s street newspaper, Spare Change.

The street newspaper was started in 1992 by those experiencing homelessness, and now the formerly homeless and other low-income people keep it going. Many of the vendors are often experiencing homelessness.

As a vendor, Thistle received papers for 50 cents each and sold them for $2 each, plus tips. Most street news vending works like this, charging a base amount to the vendors on which they can easily turn a profit; often the local office gives the vendor a small number of papers to sell for free. In this way, being a street-paper vendor offers a barrier-less path to earn money for the very low income and those experiencing homelessness. Nationwide, 27 street newspapers operate on a similar model.

“It saved my life,” Thistle tells Next City. Selling the paper “made me viable while I had the cancer,” he says.

For many years, the Cambridge, Massachusetts community would see Thistle standing outside the Whole Foods on Prospect Street, just north of Central Square. Whole Foods, he says, was nice to him as he went through the various stages of cancer, including chemotherapy, recovery, and even while he was using pain meds to cope with the pain of his disease and treatment.

The first time he sold the paper, when he was struggling in 2007, he “spare changed” until he became a case manager at the Somerville Homeless Coalition, where he worked until the throat cancer and subsequent treatment made regular employment untenable. Not being able to work, he became homeless again, and “spare changed” until he became a peer specialist at Elliot Community Services.

For Thistle, selling the paper didn’t just give him a way to earn money while he had cancer. “It got me around people I loved to be with,” he says. It gave him dignity and a sense of self-respect. And the people gave him encouragement and community when he might have felt otherwise isolated. The Cambridge community, says Thistle, “showed so much love.”

James Shearer, the co-founder of Spare Change and its board president, says that homeless newspapers survive while other newspapers nationwide are folding because people develop a relationship with the vendors.

“I think it’s the idea of helping vendors get a rapport with people. If [a vendor] disappears, we get calls asking where they’re at. They’re not panhandling. They don’t want anything for free. People respect that. It’s a job and people appreciate that.”

Tim Harris is the former co-founder of Spare Change and founder of street paper Real Change in Seattle. “After twenty-five years, what I’ve come to appreciate more and more is the real transformational power [street papers have] that changes people’s lives. It’s in the relationships that are created between the vendors and the readers. People move from being in a place of low self-esteem and hopelessness to being embedded in a supportive community of readers they interact with.”

Harris believes that the value of the street paper model comes not only in building relationships, but in changing how people view those experiencing homelessness, and how people experiencing homelessness view themselves. “Often people who’ve been struggling with addiction start selling the paper, and they feel valued as people, and they reach this point where their notion of who they are in the world doesn’t square with the dysfunctional behaviors that have been survival in the past,” he says. “They move on because they become more fulfilled human beings by finding a version of success with themselves and integrated in a supportive community.”

Israel Bayer, former executive director of Street Roots in Portland, Oregon, says selling street papers is “an old model. Street newspapers go back to the core roots of print media and the distribution of print media, selling a newspaper and informing the general public about issues that matter to them.”

Selling the paper on the street, and knowing the person who sells them to you, harkens back to the days long before the internet, or even before the paper boy’s route.

Bayer believes this model also fosters relationships “across class lines. Someone with a house may not have a relationship with someone on the street, but they can build a relationship in a safe space in a way they would not otherwise be able to,” with street paper vendors.

Street papers fill other community needs in the wake of nationwide gentrification and cost of living increases. “Our biggest accomplishment besides helping people is that most of our people aren’t homeless now,” says Shearer.

It also shifts the dialogue and raises awareness of what’s really happening. “Boston is two different cities,” says Shearer. “You go to Mattapan, Dorchester, and you see how poor it is. You go into downtown, and you see a city building huge complexes for people who have lots and lots of money, with rooftop bars and restaurants and expensive condos. There’s no real affordable housing for people.” Most people who receive housing assistance, says Shearer, end up moving out of the city.

“The Mayor of Boston likes to keep saying ‘we’re getting it done.’ No, you’re not getting it done,” Shearer charges; he is writing about this issue for the paper. “You’re building housing for people who can pay huge sums of money. The people from here, they pretty much get nothing. There’s enough for the people who can afford it. Everyone else might as well leave town. They don’t say that. But that’s what their actions say.”

Using Spare Change to raise public awareness about the shelter system is important to Shearer. When Spare Change first started, shelters weren’t very supportive: “It was a cot and a bowl of soup,” he says. “One of the things we wanted to do was to alert the public [that] they’re pouring money into a system that is unhealthy and unkempt. There was no dignity, no respect, and a real lack of compassion.”

Today, says Shearer, “They’re providing more services. Us being able to expose the fact the shelter system is inadequate [has a lot to do with that]. There’s been a lot of change since then, and I like to think we had a hand in that.”

Bayer adds that importantly, “street papers help provide investigative journalism, commentary and storytelling, helping inform the general public on a range of important social justice issues affecting the community and world in which we live.”

“Street papers are a watchdog of local and national democracy,” he adds, “helping keep the public engaged. We also help provide an authentic voice for people experiencing homelessness and poverty in the public sphere.”

Changes to the homeless shelter system like what’s been seen in Boston are often reflected in cities with street newspapers. In Seattle, Real Change has a homeless speakers bureau. Harris tells Next City that last year, Real Change vendors testified 27 times at city, county and state legislative hearings. “We make sure the voice of homeless is heard politically,” he says.

“We think of housing just like our roads or bridges or fire or police… We believe it’s in the public’s best interest to invest in affordable housing both locally and nationally.”

Real Change has also had some big wins over the years. In 2008, Seattle considered a proposal to build a new misdemeanor jail. Real Change ran an initiative campaign to oppose it. Even though they were not successful in gathering the threshold signatures to get it on the ballot, they succeeded in changing the conversation. “We took it from being assumed it was going to be built [and made it] an issue of race, class, and the intersection with criminal justice and incarceration.” They “completely flipped the tide around,” says Harris, and the three people who did support the jail — the mayor, the city attorney and the county prosecutor — all lost elections to candidates who opposed building the jail. It was never built.

Harris says they were also able to defeat “an aggressive panhandling ordinance,” among other things. Overall, it has changed the tenor of the conversation around homelessness in Seattle. They’ve been able to “achieve the magic trick of building institutional power for people who are transient.” Street papers, he says, are a great model for people to do that.

Thistle, who grew up in nearby Everett, Massachusetts, isn’t necessarily the first person you’d expect to be homeless. He has a master’s degree from Harvard. He played professional basketball in Europe and worked out with the Boston Celtics. He’s 6 foot 5 inches tall, lean, white, with sparkling hazel eyes. At his peak, he could dunk in a way most white guys couldn’t. Life was good until he hurt his knee and couldn’t jump anymore. The league replaced him, and he came back to Boston. His parents both died. Despite having money in the bank, he had no job, and with the passing of his parents, no safety net, and he quickly spiraled into alcoholism. And homelessness.

“No matter how high you’ve climbed the ladder, [lighting] a match to the bottom [of that ladder] will take you to the bottom with everyone else,” he tells Next City. Once at the bottom, “It’s very, very tough, trying to pull out of that cycle and stay positive when people don’t see you in a positive light. It’s hard.”

Despite the advanced degree, Thistle says that being older and having huge holes in his resume are problematic for potential employers. And, “I don’t believe in myself as much as I should sometimes,” he admits. “I’m not a good promoter of myself. My number-one fear is a cover letter.”

Today, Thistle is cancer-free, on disability, and receives section 8 for his apartment. “God did this,” he says.

He also credits Spare Change. “It changed my life,” he says earnestly. “Being able to get the exposure, to talk to people and let them know what was going on. It literally saved my life, because it gave me support from the community to go to treatment. It was really amazing.”

In addition to selling papers on the street, Thistle also wrote articles for the paper on the fragility of homelessness.

In the beginning, “We were a group of homeless people who wanted to get off the street,” says Shearer, because the system wasn’t working. Shearer describes the bait-and-switch dynamic of programs supposedly meant to help people out of homelessness as “someone puts the carrot out to get the horse to run, and then the horse runs and doesn’t get the carrot.” It’s a misconception, he says, that the homeless are homeless because they are lazy or because they abuse substances. “No one wakes up and says they want to sleep on a park bench,” he says.

Shearer said the idea for Spare Change was inspired by Street News, a street newspaper that was once published in New York City. Street News, says Shearer, “was started by a group of business people who sat in a boardroom and said ‘Let’s create something and let them [the homeless] sell it.’”

For Spare Change, “The difference was the homeless were going to write it and sell it and publish it — to give ourselves a voice. We made it easy to sell the paper: You come in, you get orientation, you get your first 10 papers free — back then it was 10 cents a paper then sold for 50 cents. We don’t tell people what to do with their money,” he adds. “We give them dignity.”

Shearer says that today, “Most of our writers are homeless or low income,” and the current editor and graphic artist are formerly homeless. For the first five years of the publication, which started in 1992, the operation was run by those experiencing homelessness or those who came out of homelessness while working at the paper. Shearer himself was homeless, and today supports himself with Spare Change and is on disability.

Today, “We’re stable,” he says. “It wasn’t designed that way, but we knew we had to move that way to keep [the paper] running.” When someone is preoccupied with where they will sleep at night or where their next meal will come from, it’s hard to think about putting out a newspaper. Today, the newspaper runs editorial decisions by their vendors, and Shearer says the homeless and formerly homeless still advise on everything. “Our goal is to train homeless in journalism,” he says.

Most street newspapers in the U.S. have a professional editorial team that has formal housing, but still consult with those experiencing homelessness for editorial direction, stories to tell and issues to explore and investigate. Some papers are members of the Society of Professional Journalists and have published award-winning reporting on issues ranging from investigations into the death of people experiencing homelessness in Portland and Multnomah County, to a three-part feature on one person’s troubled journey, to insightful arts reporting that included an interview with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart.

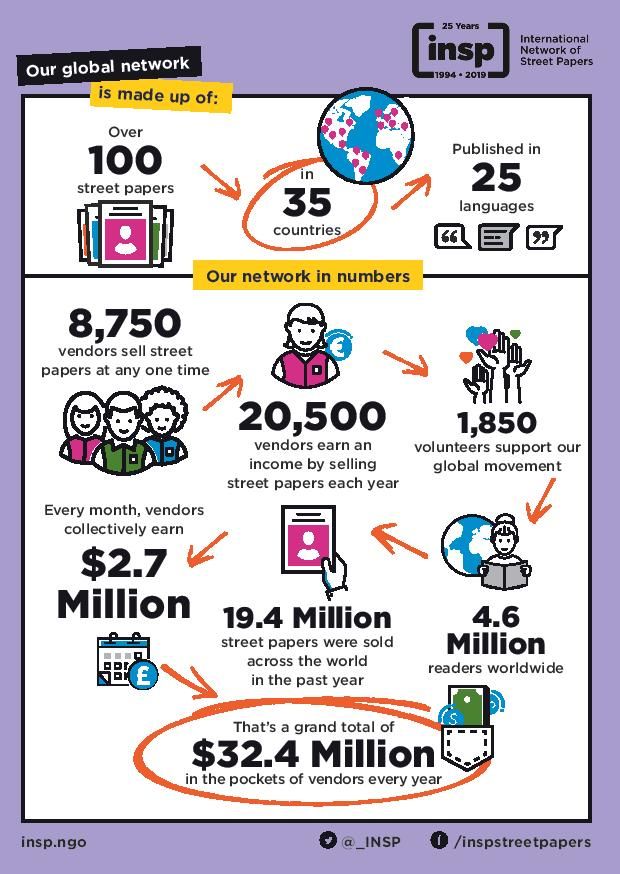

Graphic courtesy International Network of Street Papers.

Harris thought the idea of a newspaper by and for homeless people was sustainable, until a person he terms the “self-appointed director” of Spare Change, back in the paper’s early days, “broke into the Cambridge Old Baptist Church office and stole all of the computers and sold them for drugs.” Harris said the thief also left an explanatory note. “The only reason he didn’t steal the copier too was because it was too heavy.”

Harris laughs as he tells the story, including the part when, prior to the robbery, this same man fired him. “There was this amazing meeting after, where people asked how [the paper] was going to be sustainable. To their credit, they’ve survived. There were times when they barely made it. James [Shearer] has some staying power. He’s super dedicated and has tremendous loyalty to making that project work.”

Harris, a South Dakota native and high-school dropout who is well educated in organizing, says he was still sold on the street-paper model. “I wanted to organize another on a cross-class model that was sustainable for the long term and [could] build power for homeless folks.” He moved to Seattle in 1994 to start Real Change. “I wrestled with what my role as an organizer was and the whole question of how do you create an environment that is safe and healthy for everybody involved. It was a big period of growth.”

Real Change celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. “We’re recognized as the most both stable and successful street paper in North America,” says Harris. The paper has 16 staffers and a $1.2 million annual budget, with a weekly circulation of 13,000 copies. Their vendor program provides case management tailored to each vendor’s needs, and averages 300 vendors a month coming through the organization.

This is just a part of the ideological shift these street papers are helping to facilitate. “We think of housing as a public infrastructure in our society. Not a handout,” says Bayer, who is now director of the North American Bureau of the International Network of Street Papers (INSP). “We think of housing just like our roads or bridges or fire or police… We believe it’s in the public’s best interest to invest in affordable housing both locally and nationally.”

Founded in 1994, INSP is a trade organization based in Glasgow, Scotland of more than 100 papers in 35 countries and published in 24 languages. They provide technical assistance, a newswire where articles are gathered and shared, and an annual summit.

As a result of Bayer and INSP’s work, “Papers have been able to learn from each other and develop,” says Harris. In North America, 27 street papers are members of INSP.

Curbside Chronicle co-founder Ranya Forgotson, right, with vendor Chazzi Davis, who has illustrated covers for the magazine. (Photo courtesy The Curbside Chronicle)

“We learn so much from each other,” says Ranya Forgotson, co-founder of Curbside Chronicle, a 32-page monthly glossy street magazine in Oklahoma City. “Homelessness happens all over, which makes it a relatable problem,” she says. “And homelessness looks different in NYC than in OKC. And it’s way different in European cities.”

Forgotson says the issues in the UK and EU include dealing with refugees and language barriers. In the U.S., “We’re dealing more with substance abuse and mental health and incarceration and lack of education and job skills. “

And even though OKC is thought of as a very affordable city, the city is 5,500 units “short of what we need for affordable housing,” she says.

People often think the idea of a street paper or the issue of homelessness is progressive, but Forgotson says the Curbside Chronicle has been embraced by both the left and the right in traditionally red state Oklahoma. “That’s what makes us special and powerful,” she tells Next City. “People want to truly engage with and understand those that are different. We just need a safe space to facilitate that.”

Forgotson adds that, “Our mayor invited us to the table on a taskforce on homelessness, and ideally we’ll make big strides on homelessness. None of that would’ve happened if people weren’t buying into this magazine and being a part of this movement.”

Street papers nationwide have been “influential,” says Shearer. “A lot of the papers are different,” he adds. But no matter what, street papers, he says, “let people know what’s really going on.”

Shearer says that all of the members who founded Spare Change in the 1990s got off the streets. “I got off pretty quick,” he says. “I haven’t been back since.”

Yet, some folks are still on the street. With Spare Change, some vendors sell the papers for years. “We’re like a family,” says Shearer. “We don’t limit their time at the paper. They can stay as long as they want. A lot are disabled, and that’s their way of getting by. You can’t survive on disability alone. This way they don’t have to decide between rent and medication. This helps them do both. And get something to eat.”

“We try to stick close to the mission,” he says, which is simply, “Empower homeless people. It’s about helping the homeless help themselves.”

Thistle echoes how empowered he felt when working for Spare Change, both as a vendor and when he wrote articles on homelessness. “The cycle itself tears you apart,” he says. “Not knowing where you’re gonna sleep, where you’re gonna eat. Pretty much going looney. How can you look good for a job interview when you wake up on a park bench? It’s insane what needs to happen to get out,” of the cycle, he says.

“It’s been tough,” says Shearer. “Sometimes we struggle for funding. If donations don’t hit a top mark, then we suffer, but we always manage.”

“I wish Spare Change was supported more,” says Thistle. “The people who do it are phenomenal.”

Pullquote photo courtesy The Curbside Chronicle.

UPDATE: The article has been updated to correct the spelling of Curbside Chronicle’s co-founder in the photo caption, to correct the number of street papers published in the U.S. and to clarify the nature of Real Change’s vendor testimony at government hearings.

Valerie Vande Panne is a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow and a freelance writer. She travels extensively throughout the United States. Her work has appeared in Bloomberg, Columbia Journalism Review, In These Times, and Politico, among many other outlets. She is a former news editor of High Times magazine, and the former editor-in-chief of Detroit's alt-weekly, the Metro Times.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine