The first sign I had entered Pennsylvania’s 16th congressional district read “State Game Lands 52, Safe Hunting.” Forest engulfed the roadway, and then gave way to rolling farms dotted with silos and barns, and later, neat Lancaster County subdivisions sharing fences with grazing fields.

In a library in Ephrata, a rural suburb of Lancaster, an older woman told me she didn’t know a thing about her congressional district. A mother and son in the parking lot of a diner down the road said the same. But when I described the boundaries of their district all three agreed: It did seem strange that Reading, a postindustrial city in Berks County, 22 miles up the road, would be lumped in and share a representative in Washington, D.C., with the farmlands and farmers of Lancaster County.

“The differences between what Reading and [the city of] Lancaster need, and what Ephrata and Brunnerville need, that is a little different,” said Ephrata resident Isaac Boots. Inside Gus’s Keystone Family Restaurant, an older gentleman and lifelong conservative shook his head and laughed when I told him that Berks County was in fact split between four districts, and that none of its representatives at the federal level lives in the county. “Local politics ain’t so local anymore,” he said.

Carol Kuniholm, of the League of Women Voters and Fair Districts PA, agrees. She’s been preaching about the dangers of gerrymandering for over a year. Pennsylvania’s gerrymandered districts are notorious for their cartoonish shapes, disregard for existing geopolitical boundaries like county lines, and transparently political aims to create safe Republican and safe Democratic districts.

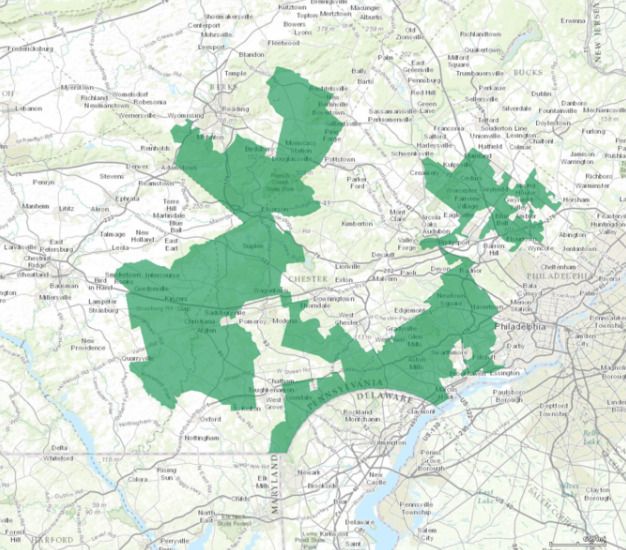

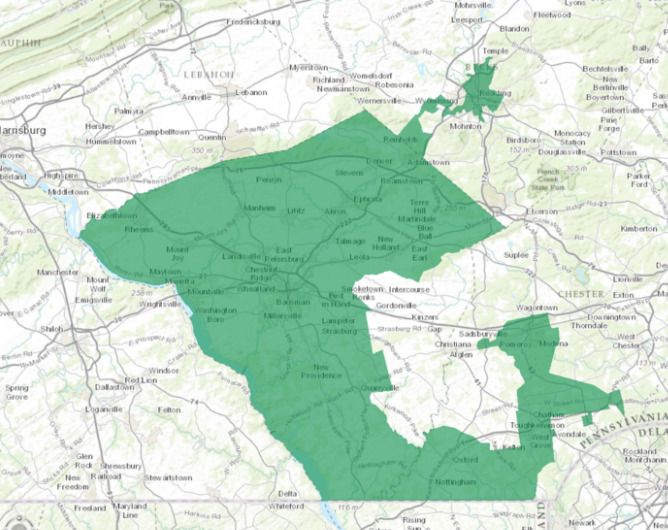

Across the U.S., states redraw their congressional districts every 10 years, based on new census data. In Pennsylvania, the majority party in the state legislature controls the lines on that map — thus ensuring that party’s dominance until the next redistricting. That’s how District 7 was formed in 2011, a meandering entity that pays no heed to natural boundaries in its quest to create a safe Republican majority. Or take District 16, which largely coheres to Lancaster County lines and then — seemingly arbitrary — sends out tentacles to snag Oxford and Coatesville in the east and Reading in the north.

Pennsylvania's 7th congressional district, among the most gerrymandered in the U.S. (Credit: One Million Scale project)

Pennsylvania's 16th congressional district. Reading is in green at top right. (Credit: One Million Scale project)

Gerrymandering, charges Judy Schwank, a state senator who represents the city of Reading at the state capital, “dilutes Reading’s ability to gain any kind of political power in terms of representation. No matter who is representing that particular district, they have a much larger portion of population in Lancaster County, which is much more Republican-leaning, which allows them to kind of ignore the needs of Reading itself. And this is a city with quite a few needs. We’re one of the poorest urban areas in the country.” Reading also has the country’s most underfunded school district.

Schwank and other reps in the state capital of Harrisburg are ready to change this process — and if they succeed in making the system fairer, that could be good news for smaller postindustrial Pennsylvania cities like Reading. They’ve introduced bills with bipartisan support that would fix the way the U.S. congressional districts are drawn by establishing an independent citizens commission. (Pennsylvania’s state legislature lines are determined by a political commission.) Eleven citizens — four each from the two major parties and three unaffiliated or independent voters — plus a commission chair would draw districts using current mapping and data software, but without access to information about party affiliation, past voting or where incumbents live. All data fed into their mapping process would be open to the public.

The maps would be presented in public hearings where residents could propose changes. A supermajority of the commission would be needed for adoption. Aggrieved citizens could challenge the final maps in court, as they can now, but at no point would elected officials get to reject or approve them. Similar measures have been adopted successfully in California and Arizona. Another possible reform proposed in one of the bills would follow the state legislature redistricting method of using a political commission, but it would bind the politicians more strictly to creating compact, contiguous districts.

Though it may be politically dangerous in the short term to advocate for such changes, Kuniholm believes in the long term it’s in politicians’ best interest. She stresses that both parties have used the flawed system to their advantage. It’s designed to yo-yo back and forth: With Pennsylvania’s next redistricting commission likely to be led by Democrats, Republicans might be swayed to support redistricting reform now, before Democrats use the same old weighted system to tip the scales back in their favor.

“This is a bad game and everybody loses,” says Kuniholm.

Districts that don’t conform to communities of interest, she says, are hard to represent. Sprawling districts that spread over mountain ranges and rivers may take hours to cross. And the system puts all of the power in party leadership’s hands: If a district is a safe bet for a Republican, the only real competition is in the primary. That tends to push candidates into more extreme views, allows party leadership to sway results by throwing support behind favored candidates, and opens the door for vicious smear campaigns. It doesn’t help that Pennsylvania has some of the least transparent campaign finance laws in the U.S.

Kuniholm also says that while a direct connection can’t be drawn between poverty and school funding on the one hand and gerrymandering on the other, “historically places that are well represented have thriving economies and populations that flourish.” And places that don’t have good representation? They struggle.

That includes the residents of Reading, where 44 percent live below the poverty line.

Driving up Route 222 from Ephrata as though I were an elected official out to survey my district, I discovered I actually had to hop off the highway and take back roads for a few miles just to stay in the 16th. The first sign I’d entered Reading was a blinking traffic billboard: “Mayor Wally Scott Welcomes You to the City of Positive Change.”

Before the 2016 presidential election, Kuniholm had been told over and over that redistricting reform was too wonky, too complicated — impossible, perhaps. But since then, she has been overwhelmed with support. The week after the inauguration, she gave a presentation to a standing-room-only crowd of over 800 people in a Philadelphia church. The following week, 400 turned out to hear her in Allentown. If a citizens commission were introduced, Schwank says that kind of interest would need to be sustained.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)