Manila’s Formal Employers Tell Butch Lesbians They Need Not Apply

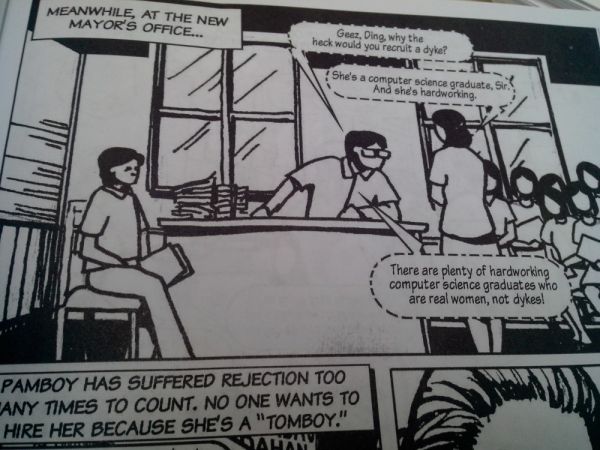

A page from “Tatsulok.”

The life of Pamboy jumps off the black-and-white pages of the comic book Tatsulok (Triangle), makes one pause a moment first before proceeding and inspires either an amused smile or a scowl, depending on the reader’s views.

As the heroine of Tatsulok, Pamboy doesn’t boast any superpowers. She doesn’t don a cape or any sort of flashy costume – far too glittery for her taste – nor does she wield any weapon or defense that might shield her from pain. Instead, she wears everyday clothes, lives in the slums, has a dependable set of “super” friends, and in the end, she gets the girl.

Yes, the girl. Pamboy is a lesbian, and a “butch” one at that. She has short hair and dresses like a man, but she is very much a woman – one who happens to be in love with another woman. Her story is not just about the great diversity of romantic love, however. In this case, it’s more about the rather unromantic task of finding a way to put food on a table.

While other countries are buzzing about legalized same-sex marriage and the Vatican’s apparent change of heart, Pamboy’s tale is a reminder that, for lesbians in Filipino urban-poor communities, sexual orientation, especially when expressed through gender-bending fashion and style, can prevent a woman from getting the work that she needs to survive.

According to Anne Lim, executive director of Galang (Respect), the advocacy group that published the comic book, this is a story that’s all too familiar for the many Pamboys in Metro Manila. Though it’s progressive record on certain social issues has crept forward – President Benigno Aquino recently voiced tacit support for gay marriage, though not gay adoption – the Philippines remains a deeply conservative place, where being too out-and-proud is frowned upon by the country at large.

For instance, in one part of the comic book, Pamboy’s application for work is rejected because she refuses to look like a straight woman. This storyline was inspired by a real-life incident – Lim said that one of the members of a group they helped form in Quezon City had her online application for an office job accepted. When she went in for her interview, however, her chances of getting the job quickly evaporated.

“The responses vary from, ‘We can’t accept someone like you’ to ‘You are immoral,’” Lim said.

Babe is working informally but hopes her persistence will one day land her formal employment.

Even when potential employers consider the applications of someone like Pamboy, Lim said, there are often conditions attached. “They are asked if they are willing to put on makeup, wear a dress.”

One butch lesbian, when her application to be a clerk at a furniture store was denied, chose to stand up to the employer. She asked if she was rejected because of her appearance. “She told the one interviewing her, ‘Has it got to do with the way I dress? I’m not selling my body,‘” Lim recalled. She ended up getting the job after the confrontation. But such outcomes are more the exception than the rule. Given the difficulties around accessing formal employment, most butch lesbians in urban-poor communities find work in the informal sector instead.

Galang has helped form LBT (lesbian, butch and transmen) groups in six Manila communities, and 60 to 70 percent of the groups’ 200 members work in the informal sector. Many are domestic workers, food vendors, or pedicab drivers, while others are engaged in contractual jobs as janitors or service crews in fast-food restaurants.

“It’s easier for them to work in the informal sector because they don’t need uniforms, don’t need to change the way they look,” Lim said. “There’s a free-wheeling existence. There are no gender-specific requirements.” It also gives them a cloak of “invisibility,” Lim said. They need not be scrutinized from head to toe – they can just work in peace and earn their keep.

The downside is that these jobs don’t pay much, and there is no security of tenure. Babe (not her real name) has worked informally both as a factory worker and an assistant cook in an Italian restaurant, but had to quit both jobs because they paid below the minimum wage of $10 per day. But the 23-year-old Babe, who looks more like a 15-year-old boy with her spiked hair and small frame, is one of the lucky ones. She wasn’t harassed for the way she looks during the hiring process as the establishments who hired were gay-friendly places.

Her friend, George, a butch lesbian, was able to find a job as a foreman at the Department of Public Works and Highways because she had a “backer” – her father, who also works at the DPWH as a foreman. Injecting every sentence with a joke that sends Babe into spasms of laughter, George, who is not considered a standard employee and therefore works informally, said she earns a little less than the minimum wage and has to pay for her own health benefits and Social Security contributions, instead of having them automatically deducted from her salary, as is typical in formal employment. George said it’s possible she will never be regularized, but she’s sticking it out regardless. “I want to stay long enough until I get regularized. I want to show others that it is possible.”

Discrimination is so rife that some lesbians seem to have internalized their status, opting to become janitors or enter other low-pay professions even if they have other skills. Galang is linked with a initiative of the Quezon City Council, in which lesbians are referred to jobs by the Public Employment Service Office. The women specify their skills and then PESO matches them to companies that have vacancies.

“Some write down ‘janitress’ when asked what jobs they want, even if they can do other things,” said George. “This is because they’ll be working with their friends and it’s easier for them that way.”

Galang also works in partnership with another government agency, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, which provides training in vocational skills. Galang has three lesbians from different LBT groups currently enrolled in the plumbing training course of TESDA, one of whom is Babe. Babe will finish the training in August, and then, “They said they can help us find a job in Canada or Australia,” she said, her eyes twinkling at the thought.

George and Babe said they want other lesbians in their communities to have decent jobs, too. They believe a national anti-discrimination bill would help achieve this goal. Such a bill has been pending in Congress for 12 years, and would penalize companies that discriminate against lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender people because of their sexual orientation. Quezon City and Cebu City have passed similar ordinances, but a national law has yet to make it onto the books.

George and Babe, along with the other members of Ugnayan ng mga Nagkakaisang Lesbiyana Laban sa Diskriminasyon (Association of United Lesbians Against Discrimination) have been pushing for the passage of this bill, but they know the fight will not be easy.

“The Catholic Church is a powerful force,” said George, who was wearing a rosary necklace. “But we should not give up.”

In the comic book, Pamboy gets a job, but almost loses it after a relative of her partner asks her employer to fire her. The story has an open ending. In real life, the true Pamboys continue to fight for a happy one.

Photos by Purple Romero