When Tokyo Was a Slum

Much of Tokyo, one of the world’s greatest urban success stories, was built incrementally. Credit: Karen Chan 16 on Flickr

This essay touches on many of the themes that we will be exploring in the Informal City Dialogues: The way cities develop incrementally and at the hands of ordinary citizens, the role of government in planning and infrastructure, and how neighborhoods integrate with the larger urban system. Through examples like this one, we hope to gain a greater understanding of how to build more inclusive, resilient cities for all.

First-time visitors to Tokyo may arrive with one of two fantasies dancing in their heads. One is the hyper-modern city of sleek 100-story high-rises and gleaming starchitecture. The other is the darker version: The city that inspired Blade Runner and Akira, a super-dense, technology-saturated metropolis in which Manga faces on towering billboards grin down on shootouts and chase scenes.

And why shouldn’t they? Such imagery, after all, speaks to a world-class city. But the fuel that powers the Tokyo economy looks, in large part, far less cinematic. Newcomers may be shocked to find that much of residential Tokyo actually resembles the low-rise, high-density habitats one normally associates with cities like Mumbai and Manila. Alongside the futuristic visage of skyscraper Tokyo, a human-scale city lies along rambling roads, where mom-and-pop stores sell soap and sandals, and private homes double as independent shops engaged in local trades like printmaking and woodworking.

This is incremental Tokyo, the foundation upon which the world’s most modern city is built.

Like much of the city, these small hamlets were smoldering ash pits 70 years ago, reduced to rubble by the bombs of Allied forces during World War II. When the war ended, Tokyo’s municipal government, bankrupt and in crisis mode, was in no condition to launch a citywide reconstruction effort. So, without ever stating it explicitly, it nevertheless made one thing clear: The citizens would rebuild the city. Government would provide the infrastructure, but beyond that, the residents would be free to build what they needed on the footprint of the city that once was, neighborhood by neighborhood.

Following the war, citizens rebuilt Tokyo neighborhood by neighborhood. Photo via the Asia Pacific Journal

What those residents built was, essentially, an enormous unplanned settlement — a settlement that, in some respects, was built much the same way that Dharavi, the huge unplanned settlement in Mumbai, is being developed today. Communities like Dharavi are growing everywhere in the world, and are often subject to hostility and neglect by officials. Yet in many ways, these places are growing similarly to the way postwar Tokyo did — a form of urban growth that created what is now widely seen as one of the world’s greatest cities. If the Tokyo’s success can be attributed even in part to the way it grew, then it’s a living tribute to the type of urbanism that now fuels the growth of unplanned settlements like Dharavi.

A City of Villages?

To this day, Tokyo is often described as a collection of villages. The American writer Donald Richie, who lived there for much of his life, described “the feeling of proceeding through village after village each with its own main street: a bank, a supermarket, a flower shop, a pinball parlour, all without street names or numbers because villagers don’t need them. Each complex is a small town, and their numbers make up this enormous capital.” Others believe this image of Tokyo is romantic and distorts our understanding of what Tokyo is all about.

According to Metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa, Westerners misunderstand Tokyo as informal and illogical because of their dualist notion of the city as divided into polar opposites: Urban and rural, formal and informal, order and mess. But Japanese culture, says Kurokawa, accepts that mess and order are inseparable: “The open structure, or receptivity, is a special feature of the Japanese city and one it shares with other Asian cities.” This is why the Japanese are so tolerant of urban forms that the West would see as “irrational” or “messy” — neighborhoods develop and slowly integrate with the larger urban system on their own terms. Tokyo was built with loose zoning rules to become a fantastically integrated mixed-use city, where tiny pedestrian streets open up to high-speed train lines.

Whether we allow such piecemeal development and retrofitting to exist in today’s cities goes to the very heart of how we will define good urbanism in the 21st century. If we assume that contemporary Tokyo is a model for desirable urban development — and many people would — we can only conclude that user involvement and incremental development have a lot to recommend them. On the surface, Tokyo and Dharavi are two places that couldn’t seem more different: One prosperous and one impoverished, the former a superpower and the latter a slum. But removed from the dualist perspective, the line that separates them is far blurrier.

Rebuilding, One House at a Time

After the war, one of Tokyo’s few abundant resources was memory — the collective recollections of millions of residents who could remember what their city had looked like before it was razed. Luckily for them, what Tokyo had looked like, even before the war, was a collection of semi-autonomous neighborhoods. The central part of the city is the historical core of Edo, which became Tokyo in the late 19th century. But the periphery grew largely without planning. Tokyo swallowed up the surrounding villages as it sprawled outward, and gradually converted small plots of farmland to residential, commercial and industrial uses. It blurred urban and rural in the process, defying one of the most important dichotomies of Western urban planning. (Today, some of those old plots are being converted back into farmland.)

In 1945, a woman tends a garden in postwar Tokyo, a city where the line separating urban and rural has long been blurred. Photo via the Edo-Tokyo Museum

Throughout the 20th century, as surrounding villages were absorbed into the expanding city and rural villages became urban neighborhoods, their inhabitants preserved some of their customs and social organization. But the central government never saw the autonomy of these neighborhoods as a threat. In fact, during the war the city relied on the self-organization of its neighborhoods for defense.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the government focused on essential needs, like the reconstruction of infrastructure and disaster relief. During the Occupation Years (1945-1952), the Ministry of City Planning produced the “War Damage Revival Plan,” basing it on modern city planning theories. A living document, some parts of this plan are still being implemented more than six decades later. In the early postwar period, however, the government put aside the plan’s most ambitious recommendations and left housing and commercial development to local actors. Tokyo’s reconstruction, especially at the neighborhood level, was largely driven by self-reliance. The housing challenge was immense.

Japan had barely built any new housing after 1937 as it ramped up its war effort, and the attacks destroyed much of this already inadequate stock. Scarce capital was another constraint. “Financial policy directed available funds to large industrial firms, not the mortgage market, and most families did not have the savings for a down payment of nearly 40 percent,” writes Gary D. Allinson in Japan’s Postwar History. People did need places to live, however, so housing got built one way or another. Between the late 1950s and the early 1970s, Japan built more than 11 million new dwelling units, increasing its housing stock by an astonishing 65 percent. Private companies and public entities provided only a small part of that — the lion’s share was created through owner-occupied single-family homes and “small rental units built and operated by private parties.”

This meant that a local construction industry, relying heavily on homeowner involvement and traditional construction practices, dominated the redevelopment of residential neighborhoods. The city quickly repopulated with people coming back from the war or migrating from an impoverished countryside, and by 1955, Tokyo had 7 million residents. It was an incredible moment in the city’s history, one where ordinary citizens excavated the skills and know-how of the past to build what would become the city of the future. They relied on vernacular knowledge of construction, and gradually, local masons, laborers and in some cases the residents themselves rebuilt entire neighborhoods, one house at a time.

It’s hard to imagine Tokyo as a vast, incrementally developing slum all the way through the 1970s and onwards. Yet in many ways that’s what it was, and this period has strongly influenced the city’s present form. To this day, one can find shops selling construction materials in most residential neighborhoods. Shack-like structures made of tin sheets and wood sit next to ultra-modern houses built of steel, glass and concrete.

This pattern of development is not unique to Japan — it can be found throughout Asia and in other places, including in Dharavi. The difference is the attitude of the Japanese government, which let unplanned neighborhoods grow and consolidate freely. It didn’t stigmatize these settlements as “slums,” nor did it discriminate against or harass them. They were treated as legitimate upwardly mobile neighborhoods, in stark contrast with the way unplanned settlements are treated in Mumbai.

Prosperity, Inch by Inch

It’s one thing to show that Tokyo developed in an incremental way. It’s quite another to suggest that this development pattern informed the city’s economic success.

But historical evidence shows that the Tokyo model of urban development wasn’t incidental to the economic rise of the city. Local construction practices, family-owned businesses (including manufacturing units), flexibility of land uses and live-work arrangements created a shadow, homegrown economy that went hand-in-hand with the city’s global-scale, export-orientated industrial development.

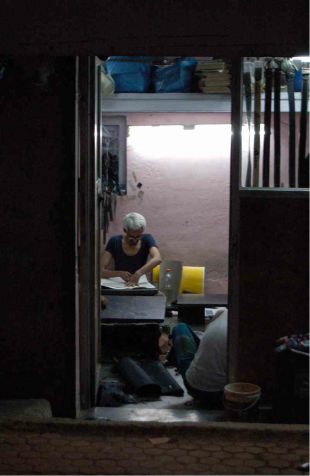

Incremental development is still apparent in Tokyo today. Photo credit: urbz.net

There’s no contradiction between being a “world-class city” and having residential houses that host printing, woodwork and other small industrial businesses on their ground floors. Today, Tokyo has far more local businesses than most Western European or Northern American cities — not just restaurants, convenience stores and laundries, but bakeries, public baths, martial arts schools, print shops, artisan workshops, offices and so on. The same small businesses that are dying in Europe and the U.S. — and are threatened in India and China — are surviving in Tokyo (though real estate speculation is threatening them, as it is everywhere).

These mixed-use habitats and low-rise, high-density neighborhoods emerged by default, not design. But though the city didn’t plan them, it considered them legitimate and supported them. Sewage systems, water, electricity and roads were later infused into all parts of Tokyo, leaving no neighborhood behind, regardless of how slummy or messy it looked. Even the traditionally discriminated-against Burakumin areas were eventually provided access to state-of-the-art public services and amenities.

The notion that infrastructure must be adapted to the built environment, rather than the other way around, is a simple yet revolutionary idea. The Tokyo model, combining housing development by local actors and infrastructure from various agencies, explains why that city has some of the best infrastructure in the world today, not to mention a housing stock of great variety and bustling mixed-use neighborhoods.

The House Is a Tool

The relationship between the city’s urban form and its vibrant economy is best illustrated by the idea of homes as tools of production. Many of the houses built in the postwar period in Tokyo were based on the template of the traditional Japanese house, in which a single structure can serve as a shop, workshop, dormitory or family house — and possibly all of those things at once. Official statistics illustrate the scale of the home-based economy. As late as the 1970s, factories employing fewer than 20 employees accounted for 20 percent of the workers and 12.6 percent of the national output in Japan. In Tokyo alone, 99.5 percent of factories had fewer than 300 workers and employed 74 percent of all factory workers, according to economist Takeshi Hayashi. What these numbers tell us is that the Japanese miracle was built not only by large-scale factories, but also relied on a vast web of small producers that often worked from their neighborhoods and their homes.

According to Hayashi, “Technological transformation in Japan took one of the following two paths: (1) modernizing traditional technologies, (2) making modern technologies traditional.”

With the second, the production line was subdivided into individual processes, and workers were instructed to move from one to another to become skilled in each major production process and, thus, to master the overall technology. These major production processes were then divided into smaller ones separated from the production line to become subcontracted work.

Hayashi explains how breaking down the line into smaller autonomous but highly integrated units made it possible for Japanese firms to compete with more advanced production processes. He gives the example of a German industrialist who, despite investing in state-of-the-art machines to manufacture “German-made” buttons from Kobe, eventually lost to Japanese competitors who had broken down the production process into “more than two dozen microprocesses, each of which became a separate job performed by a worker ‘manufacturing’ at home.”

A 1972 report corroborates this account of the organizational structure of manufacturing, stating that “subcontracting enterprises are dependent to a large extent upon domestic (household) workers and part-time home workers.” The report further explains that this domestic-workshop system relies heavily on location, since workers are organized in specialized clusters where each unit is connected to others. The modus operandi of these networked units was not competition as much as cooperation and functional integration.

Cottage industries based on small producers operating from their homes or small workshops were common in England and the U.S. until the mid-19th century, notably in the production of textiles, but also for more technologically advanced goods like firearms. The conventional wisdom is that industrialization put an end to this system, replacing the “workshop system” with the “factory system.” But in Tokyo, the workshop and the factory system were enmeshed. The capillarity of subcontracting networks, which connected large factories to home-based industries, meant that as Japanese industry grew, neighborhoods also benefited. Small businesses reinvested a share of their earnings into the improvement of their homes and workshops because those were their tools of production.

This virtuous circle uplifted the whole city. Throughout the postwar period tiny factories spread all over Tokyo, producing parts that were then assembled to produce the goods that grew the economy. This allowed the incremental emergence of an entrepreneurial class, which reinvested a part of its earnings in the improvement of their home-based factories, thus contributing to the overall development of the city. What was not immediately reinvested was saved in bank and postal accounts. The banks then lent this money to the government, and the government used it to finance large-scale urban infrastructure projects, which helped better connect the factories. The cycle continued until Tokyo had transformed into an incredibly efficient urban system, connecting neighborhoods — and in turn, industries — through a state-of-the-art transportation infrastructure.

This shadow history of the Japanese economic miracle provides a powerful counter-narrative to the large-scale, foreign investment-led development promoted in today’s developing cities. The middle-class was very much homegrown in Tokyo. Its savings ultimately produced the financial strength of Japan. And because of its urban form, investment in its economy was investment in the city’s neighborhoods themselves.

Mumbai’s Hidden Powerhouse

A model of development inspired by the best aspects of Tokyo’s development could be of use in Mumbai and other rapidly developing cities throughout Asia. Unfortunately, local authorities too often dream instead of a high-rise, car-centric city emulating Shanghai or Singapore. In Mumbai, where about 60 percent of the population is said to be living in slums, a mix of corruption, colonial hangups and institutional prejudice against lower castes and religious minorities blinds the bureaucratic elite to slum dwellers’ rights to incrementally develop and integrate with the rest of the city. Officials consider neighborhoods designated as slums to be squatter settlements on government land, and provide them with only the most basic municipal services so as not to encourage residents to stay. The government focuses not on incremental development but on redevelopment, which means clearing slums and building something else in their place.

Mumbai attracts immigrants from all over the subcontinent. Dharavi, a central neighborhood of about two square kilometers with some of the highest density levels in the world, is a testimony to that history. It was initially a small fishing village on the outskirts of what was then Bombay, but grew exponentially as migrants flocked to the city after India gained independence in 1947. Like in postwar Tokyo, newcomers built houses wherever they could, and Dharavi grew incrementally, but at a sustained pace, until it had become an imposing settlement. Today it’s a hub for cottage industries ranging from recycling activities to leatherwork, embroidery to food processing. Those who live and work in Dharavi can satisfy most of their everyday needs, from consumption to religion, within a five-minute walk from their homes.

A tool-house in Dharavi. Photo credit: Sytse de Maat

In fact, Dharavi’s urban form is simply an amplified version of the mixed-use ideal. Some uses can take over entire parts of the neighborhood temporarily: The street as a corridor for transportation becomes a market in between rush hours; religious celebrations occasionally overtake all available space for an hour or two. Though this suggests chaos when seen through the Western prism of order and mess, Dharavi is in fact an upwardly mobile and highly functional neighborhood. Most of its problems stem not from its urban form, but from the fact that it is underserved and discriminated against by the authorities. And its malleability has led to the emergence of particular architectural typologies, most notably the “tool-house.”

A space used both for living and income generation, the tool-house optimizes space in a context of scarcity. But it is also part of a culture where community ties permeate both personal and professional spaces. It’s not a new idea — the traditional artisan’s house in pre-industrial Europe was a tool-house, with the master and his family living on the second floor and the workshop (which would double as a dormitory for the workers) on the ground floor. Mumbai’s tool-house is also an avatar of postwar Tokyo’s home-based manufacturing unit. Tool-houses exist throughout Asia and the world.

Many cities have multi-functional living spaces (Tokyo is one of them), but no city has pushed the integration of functions further than Mumbai. In Dharavi, most structures have multiple functions. They can take the form of embroidery workshops that double as dormitories for migrant workers at night, family homes with small shops attached, informal home-kitchen/takeaway restaurants and priests’ homes that have a community shrine.

This extreme exploitation of space is often seen as a consequence of poverty. But relation to space — and to the people who occupy it — is also social and cultural. Throughout South Asia, even in places that are not space-deprived, it is fairly typical to see children or grandparents helping at the counter of a shop while the parents are busy elsewhere. Skills, tools and clientele are often inherited from the older generation. Community ties facilitate business transactions, as it is easier to trust people who come from the same village or go to the same temple. The house is often opened to the extended family, which includes people from the family’s place of origin. Having distant relatives sharing sleeping space on the floor for a few weeks is not unusual, even in middle-class families.

Today, many such tool-houses in Dharavi are highly integrated, technologically and economically, with global production and distribution networks, producing goods (such as leather) that are sold throughout the world. Dharavi’s development relies on post-Fordist modes of production: decentralized processes, a multiplicity of small units, just-in-time delivery and minimal inventory. Tokyo’s rise to prominence in the last decades of the 20th century was based on a similar integration of small-scale specialized production and large-scale export-orientated industries. It produced advanced consumer goods by assembling small parts created by a network of subcontractors operating at different scales. If, instead of pushing for wholesale redevelopment, the government in Mumbai encouraged a similar model in Dharavi, the entire neighborhood could bloom into a world-class manufacturing hub.

A photo collage showing Dharavi on the left and a Tokyo neighborhood on the right. Photo credit: urbz.net

For the people who live in Dharavi, this is not only the best possible outcome, it’s their only option. Most residents of Dharavi cannot possibly afford to move to other parts of Mumbai. Their futures will rise or fall with the fate of their neighborhood, which is why the Tokyo model, which values and cultivates neighborhoods like theirs, is probably their best hope for economic and social advancement.

That prosperity, however, depends on the local authorities heeding the lessons of Tokyo. Neighborhoods like Dharavi are already served by various NGOs and foundations. The residents are doing their part. The only missing piece is the support of city authorities, whose attitude toward such settlements sets back the city of Mumbai as a whole.

What’s more, the Tokyo model is simply an elegant one that follows the path of least resistance, allowing order and mess to naturally combine as they would without top-down intervention. It’s hard to imagine a better example of “development” in its most holistic dimension: Houses, neighborhoods, economies and communities all rising in concert with one another. The environment is deeply connected to processes of collective growth, because people, objects and lived spaces are all knit together by the impulse to constantly improve and transform. Through this process, with very little capital, we see how user-generated neighborhoods invest in the idea of growth and mobility, where self-interest and successful urbanism are one and the same.