Why Slum Upgrading Requires a Light Touch

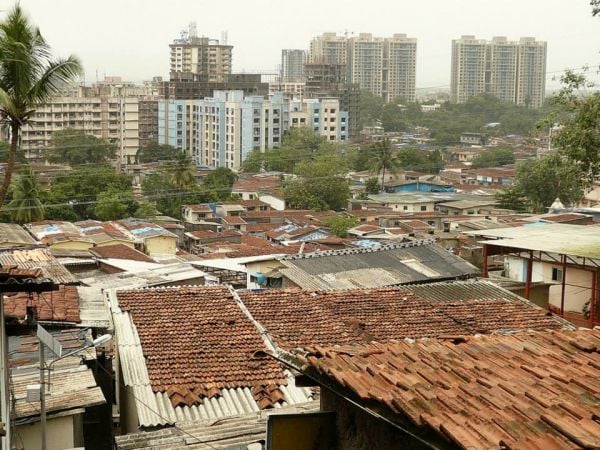

Bhandup is a hillside neighborhood. In the distance we can see the presence of high-rise buildings. Some of them are up-market, while others are cheaply built “slum rehabilitation schemes.”

In a guest blog post, the co-founders of URBZ: user-generated cities and The Institute of Urbanology argue that when it comes to slum upgrading and development, a less-is-more approach can have vastly better outcomes than heavy-handed redevelopment.

James F.C. Turner, a British-born architect who worked in Lima in the 1960s, spent much of his professional life looking at the way people provided for their own housing needs using their know-how and locally available resources. He wanted to find out how planners and architects could support those processes, rather than impose their own technocratic and context-insensitive “solutions” from the outside.

On one level he was tremendously successful and influential. His ideas led to innovative housing development schemes in many parts of the world, including in Mumbai where, in the mid 1980s, the World Bank financed “sites and services” and slum upgrading schemes directly inspired by Turner. Over 10 years, tens of thousands of people benefited from policies that encouraged them to build their own dwellings on land provided by and equipped with basic infrastructure by the state. Others were encouraged to form cooperative societies that would be given leases to the land they occupied, at once converting their status without simply “giving away” the land or privatizing it.

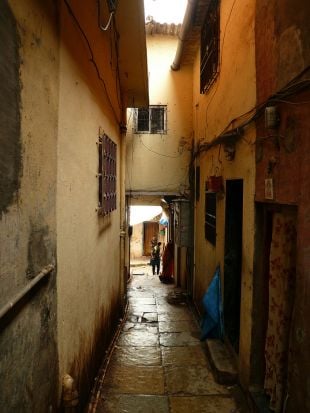

Community ties are particularly strong in Bhandup, where many residents come from coastal Maharashtra. The presence of wells as well as the architectural typology of the area attest of the the enduring presence of village ethos in homegrown neighborhoods, even at the heart of Mumbai’s 20 million-strong urban agglomeration.

Unfortunately for Mumbai, these schemes were scrapped in the mid 1990s as the real estate sector reached surreal heights and kept rising throughout the 2000s. (It continues to boom to this day). Public land became too valuable to let the poor occupy it. At the same time, officials refused to regularize the situation of its slum-dwellers, routinely referring to them as squatters and thieves despite the fact that the land they’d reclaimed was often formerly uninhabitable. Thus, Mumbai and the World Bank turned away from the progressive policies of the 1970s and ’80s in favor of “public-private” schemes that incentivize top-down redevelopment projects like the ones Turner fought against his whole life.

Today, Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Scheme is the authorities’ chief response to the challenge of improving the living conditions of slum-dwellers. It encourages private developers to clear areas classified as slums by the municipality and build high-rise housing blocks in which each family receives a free 225-square-foot unit. In exchange, the developer gets valuable “transferable building rights” on public land. This has led to the most toxic kind of developer-government nexus. A government report on the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme described it as “nothing but a fraud, designed to enrich Mumbai’s powerful construction lobby by robbing both public assets and the urban poor.”

Moreover, the quality of housing produced through the scheme has been widely described as appalling, the new buildings quickly becoming less livable than the slums they replace. Many original “beneficiaries” of the scheme have moved back to slums and sold their free flats to middle-class families who simply cannot find anything else in their budget. After decades of failed policies, the official slum population keeps rising. Today, 62 percent of Mumbaikars live in slums, according to the latest census.

The area was incrementally developed over several generations by the residents themselves. The presence of skillful builders/contractors in the neighborhood was instrumental in its development. Though there wasn’t ever any formal urban planning, it is functional and offers a better living environment than many middle-class settlements in the city.

We at URBZ have been actively involved in different neighborhoods of Mumbai – some of them classified by the authorities as “slum areas” – for the past six to seven years. Our office is based in Dharavi, a neighborhood that more than anything else struggles with its reputation as an immense “slum.” Along with many others, we have described how reducing this diverse and dynamic part of the city, where anywhere between 500,000 and a million people live, to a “slum” is the biggest disservice we can do to it. Dharavi and many other slum-classified areas in Mumbai have grown over the years, from small villages into densely populated urban neighborhoods. Their history and identity is marked by the influx of low-income, low-caste migrants from all parts of India over the past six or seven decades.

Many of these neighborhoods have improved incrementally over the years to become self-confident lower-middle-class areas. From the point of view of the new migrant, or that of the suburban slum-dweller, parts of Dharavi are aspirational. It is, after all, a centrally located, superbly connected business hub with seven municipal schools and dozens of private or NGO-run educational institutions. It has decent medical facilities and countless shrines and temples tailored to its fantastically diverse population. Over the years people have replaced their shacks with brick and concrete houses, which often double as retail or production spaces. Yet, like many other areas of Mumbai it remains under-serviced by the municipality. Excess garbage piles up, community toilets are overcrowded, and storm drains often double as a sewage system. These are some of the torments that residents of Dharavi cannot solve alone, without the active support of the authorities.

Like Dharavi, many other settlements have matured into neighborhoods that have more to lose from the rehabilitation schemes and redevelopment projects than they could ever hope to gain from them. These schemes are still at degree-zero of urban, architectural, social and economic development thinking. Extraordinarily, they are of exactly the same nature as the centrally administrated “massive housing schemes” and “high-rise buildings” of the ’60s and ’70s that Turner denounced. Isn’t it a rather unsettling thought that after all these years of trying different models and approaches, often at the expense of concerned populations, we are back to square one? The only difference is that now, instead of leading the process itself, the government seems content to simply provide a policy framework and let real estate developers and speculators do the job. Back to the 1960s – but minus accountability, and with infinitely more economic and technical means to do better.

URBZ contributed to the construction of a Sai Baba temple, which was inaugurated in May 2013. The construction of the temple was a prime example of user-generated development, as many people from the area participated financially and physically in the construction.

Thanks in part to the protection granted by elected ward representatives, which have shielded them from the worst abuses of the public bureaucracy, many parts of Mumbai have developed fairly autonomously in spite of the hostile policies. Residents of slum-notified areas are certainly suffering from the government’s biases against them, including heavy restrictions on local construction practices. Yet the scale and complexity of the matter mean that the legal framework is only loosely enforced, if at all – as is the case in most cities around the world (U.S. cities included). Many construction-related decisions in Mumbai are – by default, not by design – determined at the local level, instead of being determined by government or developers.

Like Turner, we believe that decision-making and initiatives on housing-related issues are better dealt with at the local level. In what we call “homegrown neighborhoods,” users and construction workers are often neighbors. This proximity does something that is seldom acknowledged: It increases the agency of the end-user, and along with it, her sense of identity and attachment to the place where she lives. It also keeps precious resources within the area, distributing jobs and salaries locally. Finally, it reduces the cost and increases the quality of housing. This is because local contractors rely on their reputation within the neighborhood to get more jobs. They cannot afford to break their oral contract with their client and neighbor.

Our contention is that only by working within the existing fabric and with local actors can urbanists, architects, engineers and policy-makers contribute meaningfully to ongoing user-led improvement in homegrown neighborhoods. This is why we have just started a new project called Homegrown Cities that aims to demonstrate that an alternative to “redevelopment” is possible. We want to combine our observations with relevant aspects of Turner-inspired schemes and adapt them to the contemporary context of Mumbai.

We are constantly inspired by the enthusiasm, dynamism, pride and resourcefulness of the residents, some of whom we have interacted with for a few years now. Here some of us are posing for the photo with temple committee members.

This project will start in Bhandup, a hillside “homegrown neighborhood” located in the northeastern suburbs of Mumbai, where we have been active for a few years documenting local building techniques and contributing to the construction of a Hindu temple. From above, Bhandup looks a lot like a Rio favela. Within, it has the same vibrancy and similar issues – the biggest of all being prejudice from the middle-class and the administration. This neighborhood is typically low-rise, high-density and pedestrian. It is also mixed-use, hosting a great variety of businesses within its residential fabric.

Each time we visit the area we see new houses being built by local masons and residents. Most of them are one or two stories high on a 150-to-200-square-foot surface. Bhandup residents have access to water, and electricity is available to each house. Most people have television and cell phones. No one there is dying of hunger, and there are no beggars. What this neighborhood needs most is to be recognized as a viable model of urbanization – not as a slum. Our intention is to support the efforts of its residents and local builders.

Our long-term aim is to help improve construction techniques and promote the creation of a cooperative housing society that can take an active role in managing and planning the area. We also want to provide opportunities for cross-learning and technical collaboration between residents, local builders and professionals from outside. This is a long-term project, which will develop incrementally, along with the neighborhood.

These two houses were completed in the last 6 months by Amar Mirjankar, who is our local partner for the pilot project.

Our departure point is modest and ambitious at once. We want to build a house, together with its future users and local masons that we have known for some time. Once completed the house will be sold at the same price as any other small house in the area. Houses that are put on the market locally are usually sold within two months at most because there is an enormous demand for affordable housing in the city. We will then repeat this process until we build a critical number of houses. We want to innovate as we work, learn and deepen our relationship with the residents. One of our many projects is the creation a trust fund that would allow us to put houses on lease, so that even those with no access to capital can get access to housing. If successful, we intend to repeat that model in other places.

We do not aim to revolutionize the way construction is done in homegrown neighborhoods, and we certainly don’t want to impose a new process. We simply want to contribute to the incremental improvement that is happening already, and share our knowledge and network. This will help us highlight the good practices already existing, and show that there are alternatives to the wholesale redevelopment of unplanned and incrementally developing neighborhoods. We want to demonstrate that architects, planners and others can engage meaningfully in local processes, by respecting existing morphology, supporting the local economy and bringing in their skills and creativity.

We’ve launched a crowd-funding campaign, which we hope will allow us to raise enough capital to demonstrate the validity of this approach. This pilot project can then be repeated again there and at other places, each time bringing global exposure to local actors and contexts. This hybrid model, relying on local market dynamics and the solidarity of the global crowd, should allow us to revive some of the best features of the Turner-inspired schemes of the 1970s and ’80s, while addressing some of their shortcomings.

How You Can Help

You could contribute financially via our crowd-funding page. You could “like” Homegrown Cities and share the project with your network of family, friends and colleagues via our Facebook page. You could follow us on twitter @HomegrownCities. Or you could offer your expertise in the following realms: Legal, political, engineering, fund-raising, or design. If you wish to read more about the project, please click here.

Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava are co-founders of URBZ: user-generated cities and The Institute of Urbanology. They also co-author the blog airoots/eirut. They live and work in Mumbai and Goa respectively.