#Help! Kenyans Tweet Their Emergencies, and Ambulances Arrive Within Minutes

Tweeting at the Kenya Red Cross has become one of the fastest ways to summon an ambulance in Nairobi.

On May 2, Val Okuom was eating lunch at a restaurant overlooking Mombasa Road, one of Nairobi’s busiest highways, when she saw a speeding van run over a pedestrian.

“The guy was unconscious,” she remembers. “It didn’t look like he was going to survive.”

In a country like the U.S., Okuom would have called 911. But in Kenya, the national emergency hotline had been down for fifteen years. So Okuom took action in a different way: she pulled out her smartphone and tweeted about the crash.

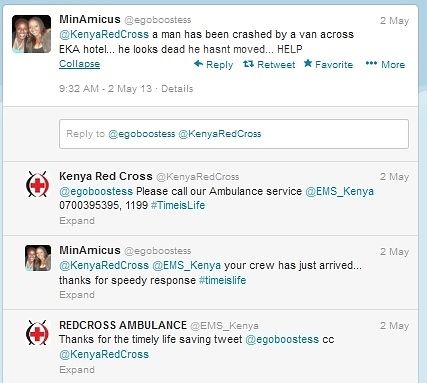

In six minutes, the Kenya Red Cross (KRC) had tweeted back. Eleven minutes after that, an ambulance was on the scene to take the victim to the hospital.

Kenya’s government has no coordinated emergency response plan, even though road accidents kill nearly 9,000 Kenyans a year, a rate well above the world average, according to World Health Organization estimates. But Kenyans have taken to mobile technology like no one else in Africa, so private organizations like KRC are taking advantage by making Twitter and Facebook the new 911.

The tweets that Okuom sent to the KRC, which saved a pedestrian’s life.

“Social media has become a key tool at the Red Cross,” says Philip Ogola, an ICT officer at KRC. Wearing a knit cap and black-rim glasses, Ogola leads KRC’s social media department. He sits in front of three computer screens and an iPad, tracking Twitter and Facebook for emergency reports. With a staff of six, his social media team works around the clock responding to emergencies across Kenya reported with their hashtag #iVolunteer.

“We thought, what if we turned the online people, the guys on Facebook and Twitter, into digital volunteers?” Ogola says of the early discussions. “So we told them, ‘If you are on Twitter, you’re an iVolunteer. If you’re on Facebook, you’re an iVolunteer.’ And it went viral.”

Now the Kenya Red Cross has nearly 93,000 Twitter followers and 20,000 Facebook likes. According to a social media data analysis program used by Ogola, he reaches almost eight million people a day through retweets and shares. Ogola says social media allows KRC to hear of more accidents faster from even the remotest regions of Kenya.

“#iVolunteer has become a 911,” he says.

Once Ogola receives and verifies an incident online, he passes it along to the KRC dispatcher, who alerts an ambulance. Pictures tweeted by iVolunteers are especially helpful because iPad-equipped ambulance crews can see the scene before arriving. Throughout the emergency response, Ogola liaises between the dispatcher, the ambulance crew and the iVolunteer on the ground, and is always sure to thank the iVolunteer online.

“I’ll actually quote you [in a tweet],” he says. “‘Accident reported by so-and-so. We responded and we’ve done the transfer to the hospital. Thank you.’ ”

Philip Ogola, head of KRC’s social media team.

KRC sent ambulances on about 8,000 runs last year, according to a spokesman, but the organization also uses social media to map frequency of road accidents and to mitigate various crises. It used Twitter to locate flood victims in the April rainy season, and averted bloodshed in Kenya’s closely contested elections with the viral #ChaguaPeace campaign (“Choose Peace” in Swahili).

And last November, a strike by Nairobi’s public minibus drivers paralyzed the city, so Ogola used the tag #CarPoolKE to coordinate rideshares between stranded commuters and drivers.

“That day we carpooled over 6,000 people,” Ogola said. “It was a 24-hour marathon – we never slept.”

KRC isn’t the only Kenyan organization to turn to social media during emergencies. The famous Ushahidi mapping system was born out of the post-election violence that rocked Kenya in 2007. A lesser-known innovation is Wanadamu, which means “they have blood” in Swahili and uses the Twitter handle @wehaveblood to crowdsource blood donors and get fresh blood to patients since most Kenyan hospitals can’t store blood.

Families of patients send “blood appeals” through email, Twitter, or Facebook to Wanadamu, saying how much blood they need, the blood type and their hospital. A Wanadamu volunteer then spreads the appeal online and consults a database of over 15,000 willing donors until he or she finds a nearby match.

Evans Muriu, an accountant in his mid-twenties who founded Wanadamu two years ago, says he receives and fulfills about one blood appeal per day, and the average time that elapses after he receives a blood appeal before a donor arrives at hospital is twenty minutes. In one case, he says a woman tweeted a blood appeal while in the ambulance on the way to surgery. She got the blood she needed and survived.

Despite these successes, disaster response remains a struggle in Kenya.

There are few trained paramedics and fully equipped ambulances, and authorities at all levels do not have emergency response plans. In a recent school bus crash that killed at least twenty students and teachers in western Kenya, a government-orchestrated air evacuation did not arrive for twelve hours despite Kenyans on twitter spreading news of the crash much earlier.

Ogola thinks official use of social media could speed things up. He recalls a collapsed building that KRC responded to after an #iVolunteer alert. The organization could not adequately address the situation because the government was slow to bring in heavy machinery.

“We don’t have the excavation machines. That’s where the government comes in,” Ogola says. “If the government employs social media it will be easy-peasy in terms of disaster response.”

Just before this story was published, Kenya police did reinstate the emergency number 999 after a court order. Still, the police don’t have an ambulance fleet staffed with paramedics, and may not have the capacity to respond to non-crime emergencies.

So Okuom, whose May 2 tweet saved a life on Mombasa Road, says she wouldn’t use the police hotline just yet.

“That would have to prove itself,” she says. “Red Cross on twitter, I’ve seen it has worked.”

Photos by Jason Patinkin