In summer 2019, Raj Chetty and several of his colleagues published a study with results that he called the “largest effect [he’s] ever seen in a social science intervention.” Their study had to do with a new housing mobility voucher program in Seattle, designed to move low-income families out of high-poverty neighborhoods. While such programs are certainly nothing new (they’ve been around since the 1980s), Chetty’s research inspired many pundits, academics and journalists to once again sing praises of mobility programs, touting them as the best or only way to deal with high-poverty neighborhoods.

Mobility programs, however, are not all their supporters tout them to be, and may even be harmful for both neighborhoods and the people that leave them. There are three main reasons for this. The first is because they leave poor neighborhoods worse off than they were before by removing potentially integral members of the community. Second, they may not benefit families all that much in the long run and may even harm them. And finally, mobility programs have the potential to result in white flight in the neighborhoods that people move to — something we’ve seen time and time again in the demographic history of American cities.

When families — especially those that qualify for mobility vouchers with stringent rules — leave a community, that drains those communities of resources. While poor neighborhoods may have some harmful consequences for residents, they are also places of community and support. Every family is a potentially vital part of a neighborhood, and removing any of them risks removing an integral facet of the community. As such, that absence can have plenty of negative ramifications. Additionally, as a neighborhood’s population dwindles, fewer local resources are available, whether that be in the form of taxes to fund schools or buying power in the local economy.

Second, while moving from high-poverty neighborhoods to “opportunity areas” may be beneficial for some families, it’s important to understand those benefits may not extend to everyone and it may even be harmful for some. Before Chetty’s time, researchers analyzed the impacts of similar types of mobility programs, and many found that they either had no impact on mover’s socioeconomic and educational outcomes or that they may have even made them worse. Even Chetty’s research from several years ago finds negative impacts of moving on certain age groups. This highlights the fact that poor neighborhoods are not monolithically bad places that people want to leave — they are sources of community and support, where their family, friends, jobs and places of worship are. Kids have established rhythms in school and friend groups, and it could be harmful for them to be cut off from that support. Even in the Seattle program Chetty’s research is based on, almost half of the families offered the opportunity to move decided to stay in closer, lower-income neighborhoods to be close to families, friends and jobs.

Third, mobility programs have strong potential to cause white flight. There is inherently a racial component in the discussion of neighborhood poverty. People of color are more likely to be poor than whites, and more likely to live in high-poverty neighborhoods, whether or not they are poor. That dictates that the majority of people who would be moving from poor neighborhoods are not white. Meanwhile, the “opportunity” areas that families are encouraged to move to are often majority-white. One of the things we’ve seen clearly throughout history is that when non-white people move into a mostly white area, the white people tend to leave and find other places to live. It’s one of the dynamics that led to the segregated cities and suburbs we have now. Most recently, white people have been moving out of increasingly non-white suburbs to gentrify the central city neighborhoods low-income people are leaving. This means that mobility programs could just end up in concentrating poverty in new places that used to be “opportunity areas.”

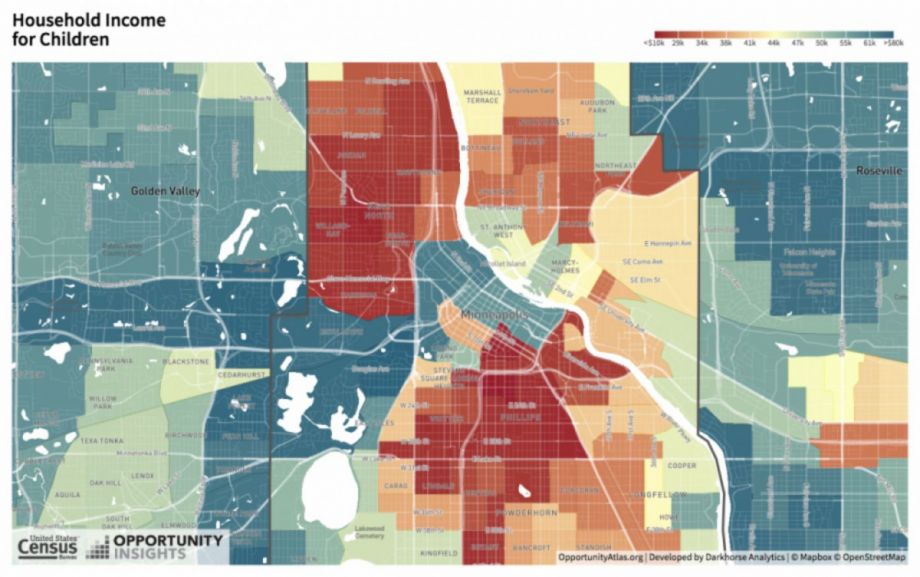

Ultimately, mobility programs may help some families escape poor and dangerous neighborhoods that they’ve wanted to leave, and that’s great. Every family should be able to make the choice of where to live for themselves. But those choices should be real, and unconstrained by the fact that we as a society choose not to invest in poor communities. The truth is that the modern-day geographic concentration of poverty and affluence did not happen by accident. It is the result of intentional public policy decisions, historical and current, that other scholars have chronicled at length.

Because we made conscious decisions to disinvest in these neighborhoods, that means that we can and should make intentional decisions to invest in them. Many fair housing advocates would say that community development can only lead to more concentrated poverty or to gentrification. But that’s not true. We can partner with communities to understand what issues they are facing and how we can solve them in a sustainable and equitable way. We can invest in affordable housing construction and maintenance and ensure that current residents get first choice in moving in. We can flood schools with resources to attract good teachers and enable students to succeed. We can invest in jobs and local businesses and make it easier for minority-owned businesses to do well. We can clean up vacant lots and replace them with parks and green space. We can build grocery stores and subsidize the outsized cost of nutritious foods. We can shift police practices to be more community-oriented and preventative rather than punitive and reactive. All of these things would go a long way toward equitable community development and allow people in poor neighborhoods to access more opportunity where they already are. They would help to capitalize on the strengths and assets of low-income neighborhoods and mitigate the potential risks.

Making the choice to invest in high-poverty neighborhoods is a more equitable and sustainable solution than mobility programs, one that fully empowers people to make the choice of where to live with no imposed bounds. Rather than making families pack up and move to find opportunity, it’s time we made the choice to bring opportunity to them.

Cody Tuttle is a Master of Public Policy candidate in the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. He holds a master’s in sociology from the University of Arkansas and his main research interests center around community poverty, housing, health, and criminal justice.