Wetlands buffer southern Louisiana from Gulf of Mexico storms by absorbing water from rainfall and storm surges. But over decades, upstream dams and canals cut for oil and gas exploration have caused these areas to disappear. The state is losing so much land so fast, that one expert compares it to losing a football field to the Gulf every hour.

At the end of March, New Orleans filed a lawsuit to hold 12 oil and gas companies, including Chevron and Exxon Mobil, accountable for the destruction of the wetlands surrounding the parish. Mayor LaToya Cantrell said in a statement that “New Orleans has been harmed” and argued that “our way of life is threatened by the damage done to our coastal wetlands,” The Advocate reported.

“Given the challenges we face when it comes to our infrastructure, the additional strain of these damages demands action. Getting our fair share means being made whole by the companies who have harmed us,” Cantrell said in the statement.

After the devastation wrought during Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, Louisiana created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to devise a plan to protect its disappearing coastline. Yet how to fund the work, estimated to cost roughly $50 billion, has remained a sticking point. While bond issues should cover some of the costs, state legislators have criticized the federal government for failing to help. And so Louisiana communities have turned to legal action to force the oil and gas industry to pay for damage it has inflicted.

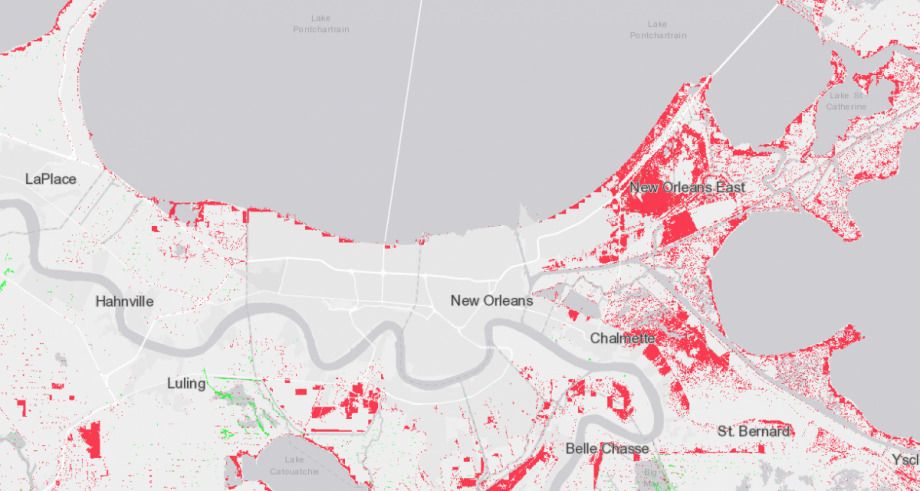

Scott Eustis, an environmental scientist with the New Orleans-based Gulf Restoration Network, points out that the loss of wetlands doesn’t harm every community equally. Communities like New Orleans East, a middle-class community where African-Americans live alongside Vietnamese-Americans, suffers from floods as the sponge-like wetlands that protect this low-lying area have melted away. “There’s a racial justice issue there. There’s a housing justice issue there, and it’s compounded by this hurricane risk,” Eustis explains.

New Orleans East, Eustis says, has been “leveed off,” separated from other areas by the levees designed to help prevent flooding. While many in southern Louisiana want concrete levees to protect their homes and businesses, the structures change the dynamics of the environment, and can accelerate land loss. The wetlands should act as a buffer between levees and heavy rainfalls and storm surges. Yet these natural storm protections have dwindled. One reason stems from the canals oil and gas companies cut through the wetlands over the course of decades. Those canals allowed for exploration and transportation, but they also introduced fast-tracks for salt water to reach further inland, killing vegetation, which causes further erosion.

The City of New Orleans declined requests for interviews for this story. Days after the lawsuit was filed, The Times-Picayune reported that oil and gas industry groups had threatened their members might withdraw funding from city events they have sponsored in the past, potentially affecting New Orleans’ famed jazz festival.

To Eustis, that’s an expected reaction — and a reason to press on. “Lawsuits don’t make friends, but lawsuits make wetlands,” Eustis told Next City. To date, Louisiana’s coastal restoration efforts have been funded in large part by settlements paid by oil and gas companies from previous lawsuits. Louisiana´s Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority announced in mid-April that nearly half a billion dollars of wetlands restoration projects were paid for by settlement monies from the 2010 BP oil disaster. The statement said that another $4.4 billion in settlement dollars are earmarked for future projects.

In 2013, three years after the BP disaster exacerbated existing problems with Louisiana’s coast, the New Orleans-area levee board took the lead on filing lawsuits against oil and gas companies seeking damages for the environmental impact to the area from decades of extraction. A few months after the case was filed, the United States Supreme Court declined to hear it. Nonetheless, the lawsuit forged a path for the region, because six Louisiana parishes subsequently followed the levee board’s lead and filed 40 lawsuits to try and obtain financial compensation for environmental damage. Last year, a national panel of judges handed the parishes a victory when it refused to bundle those suits together, which would have made it easier for the industry to fight them. The New Orleans suit is just the latest front in this legal onslaught.

John Barry, a former member of the New-Orleans-area levee board, spearheaded that 2013 lawsuit. Barry told Next City that his original aim was to bring oil and gas companies to the table to reach a “voluntary agreement” to pay for wetland restoration. Instead, he was told the companies weren’t open to this. “To me that confirmed the need to use a little bit of the stick,” Barry says.

Although that stick revealed a strategy that other communities in the area have adopted, Barry became a casualty. A few months after the lawsuit was filed, he was not nominated for re-appointment to the board. The nominating committee “didn’t want to annoy the governor,” according to one report.

Meanwhile, low-lying parts of New Orleans remain at risk.

“We need wetlands everywhere down here,” says Eustis. “We’re a concrete lily pad at the end of the world.” Because New Orleans East lies far removed from the city’s tourist attractions, Eustis argues that these impacts remain out of the public eye. In spite of that, he sustains that economic circumstances — AirBNB rentals and a hot real-estate market — are pushing many New Orleanians into this part of the city. “The tourist economy is buying up all these historic areas,” Eustis says.

While money for real-estate speculation may seem to abound in areas such as the French Quarter and Garden District, Barry says flood prevention needs a cash injection, too. “The only way to deal with climate change is with resources. [It takes a] combination of retreat [and] adaptation and the only way you can do either is with resources,” he says.

Ultimately, Barry says the investments in protecting Louisiana’s wetlands would benefit the oil and gas industry, which he says was budgeting some $1.6 trillion dollars on infrastructure when the levee board was preparing its lawsuit. The money New Orleans and nearby parishes are demanding through lawsuits to restore the environment would protect those corporate investments, Barry says. “They basically want taxpayers to pay to fix damage that they caused, but that they will benefit from because the amount of oil and gas infrastructure in Louisiana, obviously, is enormous, and all of that is jeopardized by storm surge and land loss.”

Zoe Sullivan is a multimedia journalist and visual artist with experience on the U.S. Gulf Coast, Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya. Her radio work has appeared on outlets such as BBC, Marketplace, Radio France International, Free Speech Radio News and DW. Her writing has appeared on outlets such as The Guardian, Al Jazeera America and The Crisis.

Follow Zoe .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)